XVII. Uses of Technology in Exhibition Design: A Critical Analysis of Exhibits at The Planet Word Museum

- Saskia Giramma, The George Washington University

Before my first visit to the Planet Word Museum I had no idea what I was walking into. I knew that the museum was about language and I knew that it incorporated many interactive display methods, but I did not know how those methods would be incorporated into the exhibit designs. I was excited and hopeful that I was about to discover a unique museum experience. Planet Word did not let me down. Walking into the lobby felt different than any museum I have experienced before. The space is modern; bright and sleek, with accents of vivid color throughout. While some museums feel as if the threshold is a gate and to pass through you must be worthy of the knowledge held inside, Planet Word is inviting and open. As I made my way through the space, I noticed that this museum does not rely on the display of traditional physical artifacts. Every exhibit is about some aspect of language made tangible through a variety of technologies, brilliantly and creatively crafted to facilitate linguistic experiences.

Momentarily excluding practical uses such as audio tours or wayfinding so that we can focus on the exhibit design and not the organizational logistics, at Planet Word, there are two categories of incorporating technology into exhibition design which can describe any exhibit in the museum. These are not comprehensive to all technology in all exhibition design, but rather are useful lenses with which to discuss design of an exhibition in relation to visitor experience in this particular museum. The first is to use the technology as the experience itself. This would be where the purpose of the exhibit is for the visitor to sensorily experience the technology; a projection or something on a screen, a soundscape played throughout the space, or lighting effects on a wall. The second is where the technology is used as a tool to facilitate or enhance an experience between people. There are many other motivations and intents behind incorporating technology into exhibition design, but every exhibit at Planet Word can at least be described in either of these two ways.

Where Do Words Come From?

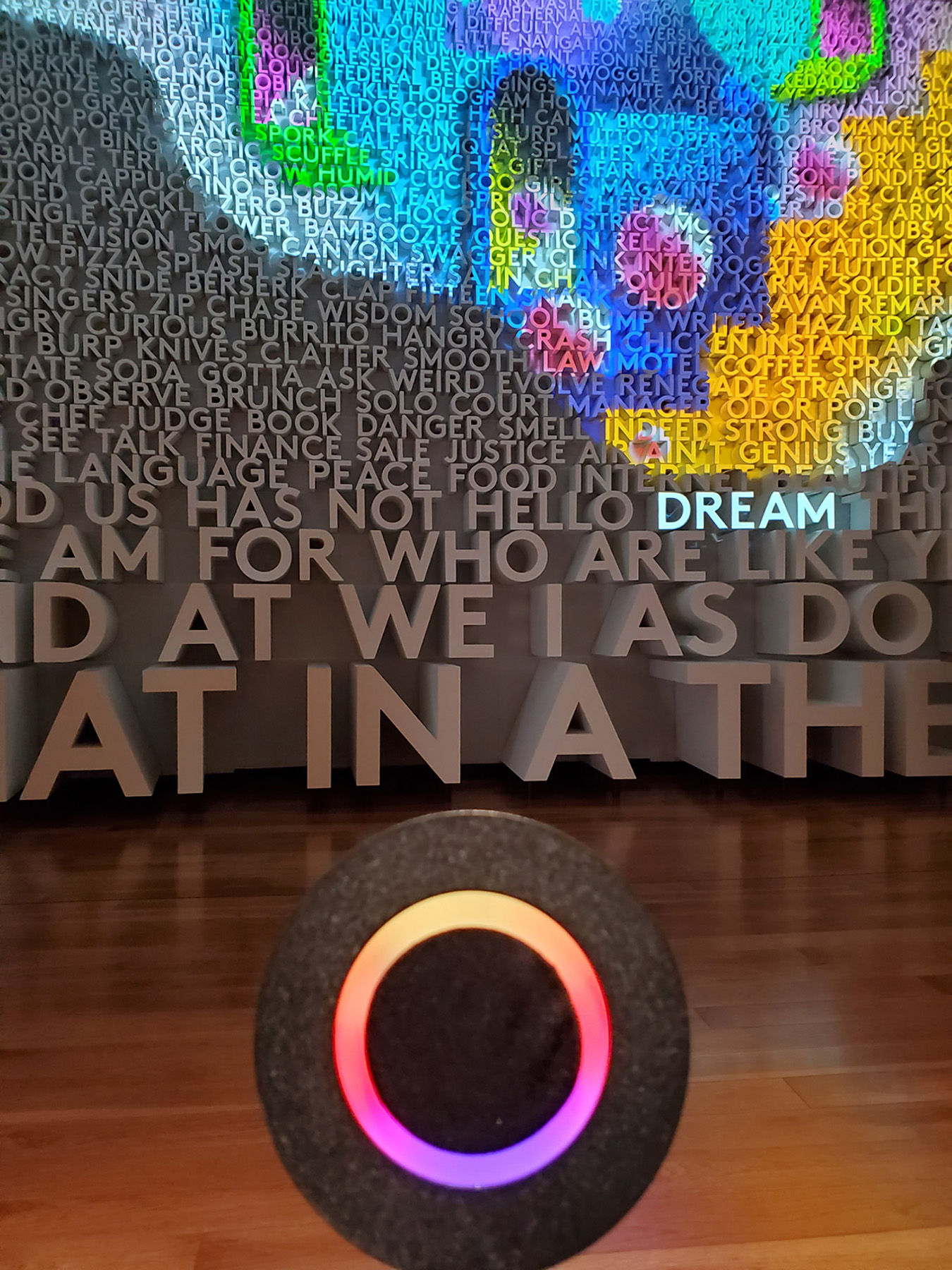

Imagine a thousand words written out on a white piece of paper. Now imagine that piece of paper is thirty feet high. Words at the bottom of the page stand as high as your waist and get smaller as they go up until the top is barely legible. Now imagine these words are three dimensional, they pop out of the page, off the wall, as physical objects in the room. This is what it is to stand in the exhibit entitled Where Do Words Come From?. In the middle of the room is a row of benches behind a line of microphones. The room darkens, a voice plays over speakers, and the wall of words lights up through a series of projectors hanging above the benches. The projectors use light and shadow to highlight certain words at certain times and use colors and shapes to communicate ideas graphically. The voice through the speakers leads the visitor on an interactive journey through the history of language and particular linguistic devices. The voice asks questions and the flow of information changes based on the first word spoken by a visitor which is picked up by the microphone. At the beginning of the program the voice explains that some English words come from French, some from Germanic languages, and some from Latin. But there are many words in English that do not come from any of these three roots so the voice asks “But what about all those other words? Now it gets really interesting. Say one of these and I’ll show you.”1 The structure of the rest of the program is determined by which word the microphone picks up first.

This exhibit falls under the category of technology as experience. The room is devoted to the projection on the wall and the visitor’s role is to sit, experience, and engage with the color, light, and sound. To make this exhibit successful the designer is relying on some nonverbal cues, the instructions given by the voiceover, and the trust of the audience. Darkening the space and directing focus to a lit projection area creates the environment of a movie theater. Going to see a movie is a somewhat ritualistic experience. You enter the room and if the lights are on you know that you are allowed to keep talking, but as soon as the lights go out and the screen awakens you know to be quiet and pay attention. The mimicking a movie theater in the design of this space actively discourages interaction between visitors while the projection and voice are playing. As opposed to a movie theater, however, the verbal direction of the voiceover lets the visitor know that there is an expectation of interaction with the screen.

The first time I experienced this interaction I was convinced that the microphone in front of me was simply a prop and that the program wasn’t actually listening to my voice and the voices of those around me. My second visit was highly informative. I watched the projection and realized that it was slightly different than my first experience. In speaking with a staff member in the area, Charles, I learned that the program does, in fact, listen to the words spoken into the microphone. It picks up on the first word uttered within a certain time frame and changes the response based on that one word. The voice creates a dialogue between itself and the visitor. The call and response format creates a desire within the visitor to influence the technology in front of them. I wanted the computer to pick my word because I wanted to see how it would react to my choices. The success of this exhibit relies on the visitor’s trust that they are not being tricked by the technology. It was frustrating to feel like the artificial voice wasn’t listening and that the signal for me to respond was slow. There were times where I became frustrated with the exhibit which I’m sure was not the intent of the designer.

Unfortunately, the instructions from the voiceover on when to speak are a bit vague. “See these mics? They’re for you. Any time you see this icon, it’s your turn to talk. It’s ok to talk at the same time, I’m listening.” 2 Firstly, the voice assumes that you know you are sitting in front of a microphone. When most people think of a microphone they picture a rod with a bulbus end. The microphones for this exhibit at flat circles on a stand which could easily be mistaken for speakers rather than microphones. The only visual connection between the voice’s instructions and the microphones is the icon used to indicate that the visitor should speak, a spinning rainbow of light. This icon is mirrored in the microphone itself which has a circle of rainbow light in the center which brightens when the same circle appears on the wall. Secondly, the voice tells you that talking over each other is acceptable and implies that it can hear everything that is said. In reality, it only hears the first word to be said at the correct time. Often the voice will instruct the visitor to pick a word or answer a question and then, a second later, the circle will appear. My friend had a tendency to start speaking as soon as the voice gave instructions rather than waiting for the light. He became very frustrated when his word was not picked. I noticed that this lag not only incited frustration, but additionally caused visitors to lose interest in the show presumably because they did not feel they were being listened to. Once I got the hang of the timing, though, the interaction with the projection became fun and interesting.

In some cases the program would react to a visitor’s choice simply by responding to the word or changing the trajectory of the program, but other times the program’s reaction was in the form of shapes or light that would show up on the wall. In attempting to explain onomatopoeia, the projector highlights a series of words on the wall: buzz, sizzle, pop, sprinkle, splat, and so on. The voice prompts you to shout out words and when it hears one a graphical representation is projected onto the appropriate word, almost as if the voice and the projection are attempting to reward the viewer’s participation. I observed, in myself and on the faces of others, a sense of delight and empowerment in provoking a reaction from the technology in front of me. This feeling of joy in provoking response from technology would be mirrored in further rooms and is, I believe, one of the reasons why touch screens and other types of interactive technology can be so captivating.

The Spoken World

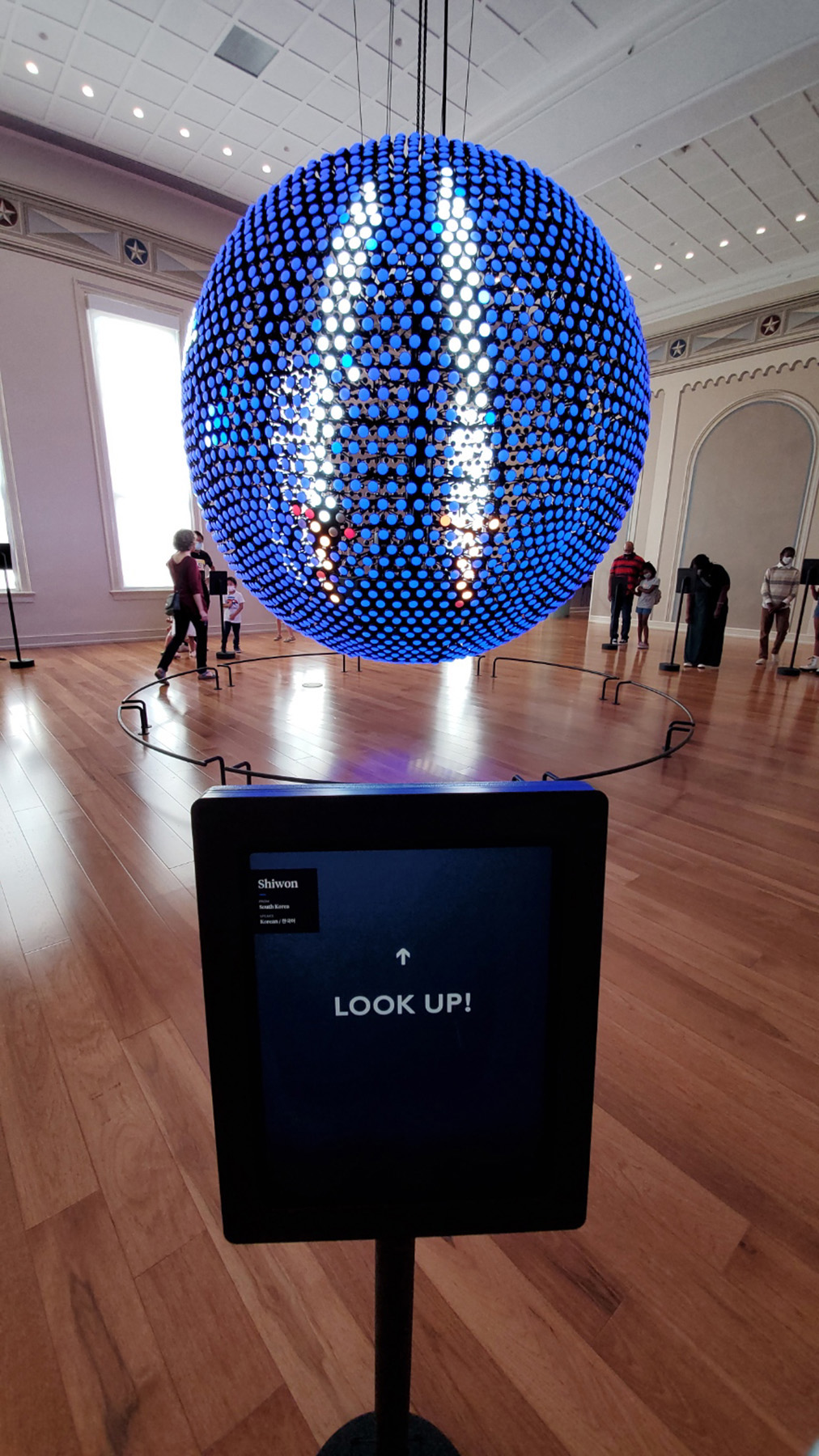

The exhibit where I think this response and reward system is most evident is called The Spoken World. This room is large; with high ceilings and, unusually for a museum, tall windows all across one of the walls which let in sunlight. In the center of the room, suspended from the ceiling, is an enormous globe made out of hundreds of small, LED circles which are colored in just the right way to create the earth’s continents out of light. Surrounding this globe, standing on the floor, are individual touch screens on stands. Each one has an image of a person from a different part of the world and a word in their native language. The ethnicity of the person on the screen correlates to its placement in the room compared to the globe. For example, standing in front of eastern Asia, the Pacific Islands, New Zealand, and Australia, I was presented with the image of a young South Korean woman.

She said hello in her language followed by a written prompt on the screen to repeat the word. When I touched the screen or spoke the word out loud the woman began teaching me a few phrases in South Korean and a few fun facts about sentence structure. When she was done, she said goodbye and an image of an older Maori man replaced her to repeat the process. I have not listened to every person in the exhibit, but I have experienced enough of them to know that there are about six or eight different languages per screen, they are grouped by geographic location, and the visitor has no control over which language will be shown next.

Periodically the person will stop and ask you to repeat a word or a phrase. About three quarters of the way through each video, after the most difficult word or phrase, the screen directs you to look up and the circular lights on the globe change their colors to create a short moving graphic relating to the word or phrase you just spoke.

The first time I experienced this, I was so surprised and excited that I practically yelled at the globe. I wanted to move to every single touch screen in the exhibit just to see what the lights would do for different words or phrases. Eventually my friends had to pull me away or we would have spent all day in that one room.

This exhibit falls into the category of digital technology as a tool to facilitate human interaction. Yes, the largest object in the room is the light up globe and yes, you are watching a film on a screen, but in my experience the result of the technological interaction in this space is to prompt a conversation within your group. This exhibit creates a short conversation with the recorded person across space and time rather than a one sided interaction with a digital reproduction of a person. On my first visit watching these videos sparked lots of debate about language or laughing together about how we were utterly unable to pronounce some of the words or phrases. My friends and I talked amongst ourselves through our entire time in this room and reveled in the graphic rewards together. Not providing headphones for this touch screen interaction turns the experience into a communal one. Other screens around the museum do have headphones and those exhibits create a very solitary experience. On my second visit to this space I was alone and I found the experience to be not nearly as enjoyable as it was with my friends. I listened to a few of the videos on the screens, but without others to talk with about the languages I quickly lost interest. If there had been more people in the space I could have, potentially, connected with strangers through the shared experience, but since the room was mostly empty I found myself feeling lonely and craving social interaction.

Joking Around

Perhaps a more explicit example of an exhibit which facilitates human interaction is one which can be found in a room titled Joking Around. This room is bright like The Spoken World because it too has windows. Three stations of curved yellow couches facing each other fill the space. In front of each couch is a touch screen. Each screen shows a joke and challenges the viewer to make the person sitting across from them laugh. First to elicit five laughs wins the game.

This exhibit could achieve the same outcome without a single piece of digital technology, but the screens allow a number of things which an analog exhibit would not. First, a computer database can provide many more jokes than an analog space. Without using digital technology I would probably design this space as a wall with jokes written across it between the two couches so that friends could tell each other jokes without seeing the answers written on the wall. However, this would ultimately constrain the amount of space available for jokes. Second, the users can be placed opposite each other without a large barricade between them which is what would happen if previously mentioned wall were involved. Third, the computer can keep track of scoring so that the visitor only has to worry about being funny, and not counting how many times their friend has laughed. And fourth, as a bonus, there is potential for each visitor to experience that warm fuzzy feeling of delight when they get to press buttons on a touch screen. While there are some nice touches added by the digital aspect of this exhibit, ultimately it is facilitating an interaction between human beings rather than an experience of digital spectacle.

Word Worlds

While many of the exhibits at Planet Word take on aspects of both categories I have described, an exhibit called Word Worlds falls plainly under the heading of digital spectacle. The room is much smaller than any I have examined so far and is an almost perfect cube. Three walls are covered in a seamless projection of a photo-realistically illustrated outdoor scene shifting from forest to grassy hills, a lake, and then into an urban setting. At about waist height is a counter with cylindrical cutouts spaced out along it. There are a few objects which look like a cross between a PlayStation controller and a paintbrush sitting in the cut outs. When you dip the controller into a cutout you hear a sound like a paintbrush being dipped into a can of paint. There is nothing to indicate that these are meant to be paint cans except the sound so on my first visit to this room I was very confused about what I was supposed to do. Each cutout has an adjective written out in the projection right above the cut out; corpuscular, magical, nocturnal, surreal, autumnal, verdant, and a few others. As you move the brush end of the controller along the wall it changes the style of illustration to match the word of choice. In this way the visitor can make a visual connection between a word and its meaning. When you brush the wall with the adjective ‘Magical’ colors become deeper and digital sparkles appear beneath your brush. As you move over the frog next to the pond he turns into a handsome prince, the airplane in the sky turns into a dragon, and the house in the woods turns into a fairytale castle.

This exhibit relies entirely upon digital technology instilling wonder and excitement in the mind of the visitor. However, the technology involved in this exhibit is projection mapping, combining a motion sensor with a projected image so that when a movement happens in a certain way it influenced the image, which is a notoriously finicky technology. On my first visit to this room something wasn’t working properly. It may have been low batteries in the paintbrushes, it may have been a bug in the projection mapping code, the sensors may have been out of alignment; whatever the cause, when I dipped the paintbrush into the different word cutouts the brush did not change and when I moved it along the wall, the image did not line up properly with where I was moving. Not only was this frustrating, but because there is very little text in the room to instruct the visitor so I did not know what was supposed to be happening and therefore did not know what the problem was. Because I have some experience with the technology involved, I knew that something was not working the way it was supposed to, but the average person off the street does not necessarily know what projection mapping is and would probably have just thought that the exhibit was poorly designed. These types of digital spectacle exhibits can be absolutely amazing when they function properly, but when something goes wrong it tends to go very wrong; they are high risk, but high reward.

Something For Everyone

Use of digital technology in museum exhibits can be risky, but that is true of any type technology used in any space. Things break or need troubleshooting, but visitors understand that that can happen and, hopefully, are patient with the museum and don’t let that ruin the experience. Overall, Planet Word does a phenomenal job of integrating digital experiences into their exhibits. Some are more successful than others, relying too heavily on specific technologies which may or may not work all the time. The most successful exhibits are the ones which use technology in combination with spatial design. The word wall is incredibly powerful because it uses physical space to create an atmosphere to facilitate the technological experience. Some of these exhibits fall flat simply because some people just don’t enjoy digital experiences. But audience preference is present in a more traditional type of museum as well. Some people spend hours looking at one painting on a wall. Personally, I walk through a traditional art gallery in minutes, stopping at each piece for only a few seconds before moving on to the next. Planet Word has a variety of experiences even within the category of digital technology. I believe that there is something for everyone at this museum. Even if technology is not your favorite medium, I think everyone walking out of this space will be able to pick at least one exhibit that they enjoyed.