IX. The Revival of the Ancient Silk Road: Use of Modern technology in Digitization, Virtual Repatriation, and Exhibitions of Dunhuang Mogao Caves

- Zhujun Hou, The George Washington University

Modern technology has brought new blood in reviving long-abandoned historical sites on the Ancient Silk Road—the Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Dunhuang, a cultural heritage site located on the ancient Silk Road in Gansu province, China, has survived for more than fifteen hundred years.1 The site reached its golden age when the trade and cultural exchange on the silk road was most prosperous, but it began to decline from the Ming dynasty of the late fourteenth through the mid-seventeenth century. Dunhuang was the crossroad connecting the East and the West, mainland China with the civilization of the Mediterranean. Suffering from Chinese civil unrest during the nineteenth century, the Dunhuang relics were looted by western explorers such as Aurel Stein and Langdon Warner and scattered throughout the world.2

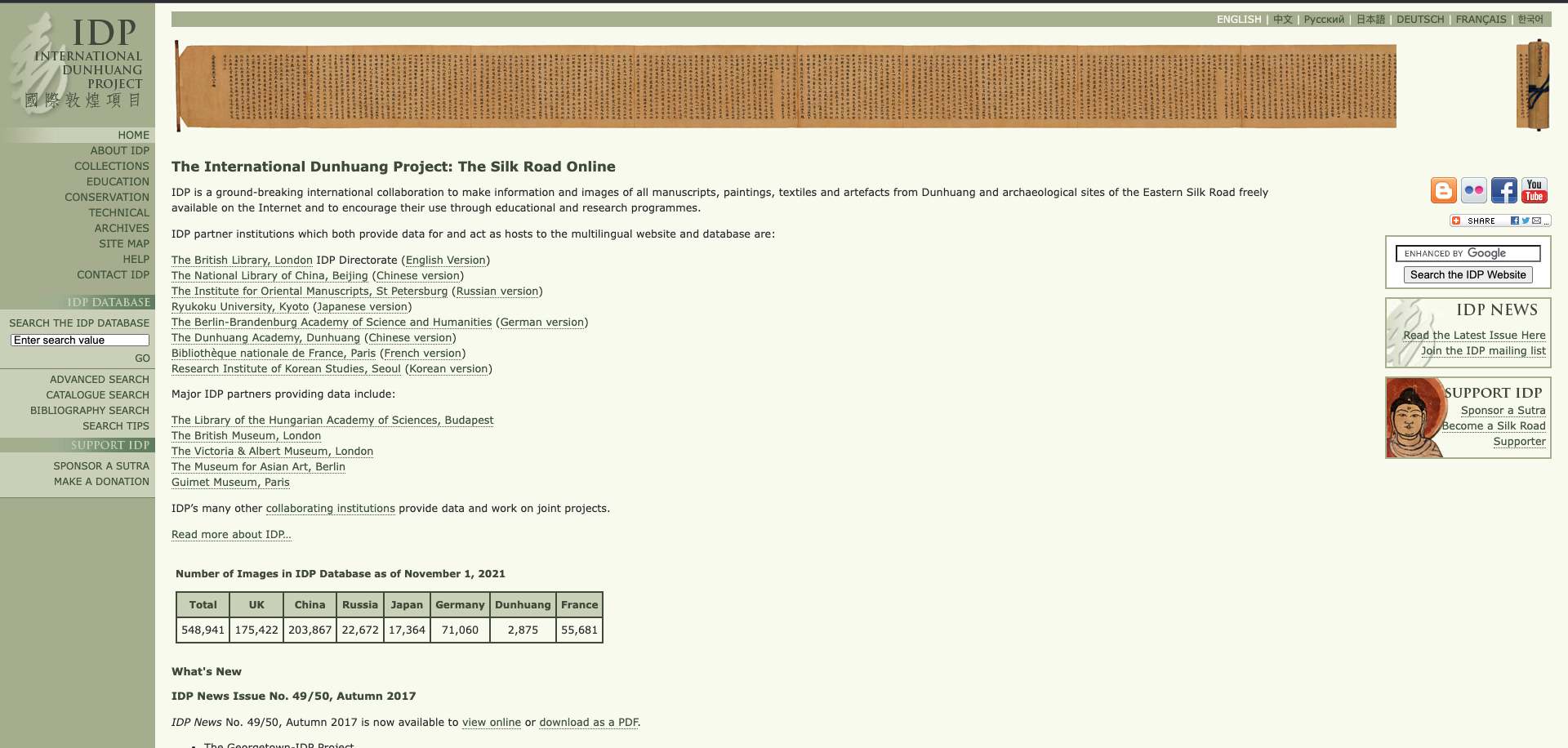

Nowadays, international collaborations are working on-site preservation, digitalization documents, and establishing exhibitions. The International Dunhuang Project (IDP), starting in 1994, created a database that cataloged and digitized manuscripts, printed texts, murals and paintings, textiles, and artifacts from the Mogao caves. This online database is essential to international scholars, Buddhist practitioners, and Chinese people and their cultural identity. The IPD database, together with immersive exhibitions, could act as a form of virtual repatriation when the physical return of the relics is not feasible.

Brief Introduction of Dunhuang Mogao Cave and the IDP

Dunhuang Mogao Caves, which were carved into the cliffs above the Dachuan River, was the home for rare cultural relics and Buddhist arts.3 Four hundred and ninety-two caves hold about 45,000 square meters of murals and more than 2,000 painted sculptures, representing the highest achievement in Buddhist art from the 4th to the 14th centuries.4 The Buddhist artifacts from the Mogao caves provide evidence for the evolution of Buddhist art in the northwest of China, which depicts “medieval politics, economics, culture, arts, religion, ethnic relations, and daily dress in western China.”5 Dunhuang not only serves as a house for Buddhist art, but it is also where social, cultural, religious, artistic, and economic trade encounters. A German explorer, Ferdinand von Richthofen, named it silk road; a historic network that prefigured the contemporary definition of globalization. However, Dunhuang lost its global charisma when the Ming dynasty took control of China in 1368 AD. The trade was disrupted by irregular warfare and constant shifts of political power in Central Asia. Due to a lack of political and military protection from powerful regimes, local banditry prevailed and threatened traders and local citizens.6

On May 26, 1900, Cave 17, the Library Cave, which contained about 50,000 manuscripts written on paper, silk, wood, and other materials, was discovered by a Chinese Taoist monk named Wang Yuanlu.7 The Library Cave discoveries are the documentary of “Buddhism, Taoism, Manicheanism, and Nestorian Christianity in ancient Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur, Central-Asian Brahmi, Turkic, and Syriac."8 Taoist Wang sold countless manuscripts to Japanese, Russians, and Stein during his third adventure. During transportation from Dunhuang to Beijing, many relics were lost or stolen because of the recklessness of the Qing government officials. Western explorers came to Dunhuang, “purchased” manuscripts, literature, peeled murals of the wall, and detached sculptures from the cave. Harvard professor Langdon Warner, who specialized in Chinese art, went to Dunhuang to study Chinese literature, history, and language. He purchased a Tang dynasty painted, kneeled attendant bodhisattva from cave 328, and brought it back to Harvard, which remained to be Harvard Art Museum’s permanent collection since then.9 A Hungarian-born British explorer, Aurel Stein, arrived at Dunhuang during the time of civil unrest in March 1907.10 Stein acquired thousands of cultural relics from the Library cave, including the old copy of The Diamond Sutra, the oldest printed book that remains today, which was divided by several institutions.

The international endeavor assembling the fragments of the Dunhuang collection was the International Dunhuang Project.11 The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) started in 1994 with the mission “to promote the study and preservation of the archeological legacy of the Eastern Silk Road through international cooperation.”12 The project offers international insight by combining local training academies with a global network of scholars and international conferences.13 The collaborative teams put the information online, covering the subject ranging from manuscripts to textiles, paintings and artifacts. The online site is freely accessible, easy to operate and extremely functional for both scholars and laypeople.

From 1993 to 1995, the collaboration focused on categorizing the collections and conservation. Digitizing manuscripts began in 1997 and in 1998, the IDP website was open to the public including “50,000 paintings, artifacts, textiles, manuscripts, photographs and maps.”14 Digitized images of 20,000 of these items are available online and the websites were redesigned and updated in 2005. The local centers were established in London, Beijing, St. Petersburg, Kyoto, and Berlin, where collections of Dunhuang relics were held and were digitized in the database. The collaborative institutions include the British Library, the British Museum, the Dunhuang Academy, the National Museum in New Delhi, the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, to name a few.

The website not only contains digital images and information for the collection, it also offers access to related links, history of Chinese bookbinding, Buddhist documents, the archive of IDP newsletters, and the timeline for this digital project. The designers considered “search terminology, available indexed fields, issues concerning the images of the items themselves, and the availability of translations for portions of specific manuscripts” when constructing the site to make the database more accessible to various audiences.15 In addition to the related links, the website also contains information on how each collection could be accessed in person. For example, the Chinese collection catalog gives people a glance at what they can access in China.

The Advanced Search button is a powerful tool to use. On the left side of each page, the “Search the IDP Database” option is available for the viewers to only search for items with images. The term image refers not only to scanned photos, but also digitized objects accompanying an entry such as maps, artifacts, manuscripts, and other items related to that entry. The advanced search allowed the researchers to search by “pressmark, by index values , and by free-text searching within titles and catalog entries.”16

Searching by pressmark is similar to finding materials in an archive by using a database accession number. Those numbers are closely associated with specific institutions or the expeditions related to the discovery of the items. Take the IDP number OR.8210/S.767 for example. “OR” represents the Oriental section in the British Library, “8210” stands for Stein’s second expedition to Dunhuang, “S” refers to Aurel Stein and “767” is the number for that specific item. Searching by index values allows viewers to conduct very specific research for a particular artifact type, holding institution, or other options.

Many challenges and concerns emerged when developing the database. High-quality digitized images could not be permanently stored since the project required a great amount of space for any system to deliver without delays.17 The expense, time, and possible damage during the digitizing process had to be concerned. Ancient paper and other materials in Dunhuang collections are extremely vulnerable to light, which is inevitable in the photo digitizing process. Thus, the team carried out a more rigorous guideline for imaging of the artifacts to avoid possible damages. Since the collections are uploaded on websites, people are concerned about copyright protection. The technique to insert hidden encoding of messages into images solved this problem. The message will show up in the image reproduction, such as photocopying and compression.

Arguments for Repatriation and why it is important

The IDP database not only offers people free online access to the Dunhuang collection, but could also reconstruct the cultural heritage on a digital platform and fulfill some roles as repatriation. Repatriation or restitution means the return of cultural materials or material heritage and human remains to their original cultural context or nation from museums, universities, or other institutions.18 Arguments for the repatriation of Dunhuang cultural relics have been going on for centuries. James Cuno, the president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, argues against repatriation, indicating that collections that are kept in museums and galleries outside China serve the purpose of education, disseminating knowledge, and eliminating ignorance.19 In the case of the Harvard Dunhuang collection, the Harvard Art Museum suggested that the removal of Buddhist sculptures and murals from the cave was to preserve the cultural relics. To better understand Asian art as fine art rather than material art, the Harvard Art Museum actively planned an expedition to China to require authentic artworks that could be used in establishing Oriental studies and Asian art history apartments. The art historian Landon Warner reached Dunhuang in 1924 when he decided not to only admire the cave himself, but to bring the murals back to school during his first expedition funded by Harvard.20 Warner used a special chemical compound to remove murals from the wall; however, he unexpectedly broke the fresco and left marks on the site. Warner brought the murals back and displayed them in Fogg Museum until the museum renovation in 2008.21

Sanchita Balachandran, the associate director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies, pointed out that the original intention of Langdon Warner’s exploration of West China was to identify, excavate and collect antiquities for the western museums.22 She believed that although Warner was regarded as an “arrogant, opportunist, and insensitive creature hunter,” he was deeply respectful of Dunhuang culture and relics and concerned for protecting and appreciating Dunhuang’s antiquities.23 Although Warner destroyed the sites and damaged the integrity of the original context in the name of preservation, his action called for the protection and examination of the Chinese government and scholars on Dunhuang Mogao culture.

Although there was no government official announcement asking Harvard to return Dunhuang objects, the Chinese State Administration of Cultural Heritage declared boycotting auctions of looted and stolen Chinese cultural objects and maintaining the right to restitute lost antiquities.24 A professor from Guangdong Academy of Social Sciences, Zuozhen Liu explains why cultural relics, cultural heritage, and cultural identity are so important for Chinese people and the community and should be returned. Cultural relics are the symbol of China’s long and continuous history, which plays an essential role in establishing Chinese cultural identity.25 During the passage of time and the changes of dynasties, abundant cultural relics which contained historical information were left for historians to interpret. In the case of Dunhuang manuscripts, a scholar of Dunhuang studies Rong Xinjiang stated that ‘Dunhuang manuscripts had provided unprecedented insight for researchers on the history and civilization of China and the world.’ Dunhuang manuscripts are valued for both their ‘originality’ and ‘antiquity.’26

Additionally, cultural relics represent Chinese culture which western scholars use the term ‘culturalism’ to distinguish Chinese civilization from others.27 Chinese ‘culturalism’ consists of two parts: ‘the belief that China was the only true civilization, and strict political adherence to Confucian principles.’28 For Chinese people, the definition of being Chinese is to behave property following the social norm and have a sense of belonging to this great civilization. Chinese art is used as an expression of social norms and as a document for social, political, economic, and religious events. Since cultural relics have a close relationship with Chinese history and culture, they are believed to be ‘instrumental’ to define Chinese cultural identity.29 The repatriation of cultural relics that had been stolen or looted to their original context is believed to show respect to the culture.30 The public of China felt offended and furious when they learned that numerous Chinese cultural relics were looted and scattered around the world. The cultural objects that were lost during war times remind the Chinese people of the bitter and tragic history of being defeated and treated unequally. The loss of cultural relics is parallel to the decline of the nation.31 The cultural objects are endowed with cultural values that can only have meaning in its original context. Chinese people are requiring the return of lost antiquities to heal their still bleeding wounds. To return Dunhuang Mogao relics is to show respect to Dunhuang culture. And by returning the looted objects, the broken trust between west and east could be fixed.32

To prevent future controversies on the ownership of cultural property and future looting of cultural relics, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Culture Organization (UNESCO) implemented regulations on international museums that forbid importing or purchasing any piece that might have been illegally taken after November 17th, 1970.33 However, the Tang dynasty murals and sculptures that were removed by Landon Warner before 1970 were not under the protection of the UNESCO convention, and the debate on whether the relics should or should not be repatriated was not settled. The repatriation would be undisputed from moral aspects if the acquisition was stolen or illegally obtained from an identified cultural group. However, as there is “no compulsory jurisdiction, no retroactivity of existing convention, the post-war settlement, and the principle of extinct prescription,” the request for repatriation is nearly impossible to achieve.34

Therefore, can digitization of the Dunhuang collections be a form of virtual repatriation when physical repatriation is not feasible? Helen Shenton, the Head of Collection Care at the British Museum in 2002, has written that digitization of dispersed collections not only “enabled the reconstruction of cultural heritage but also vastly enhanced revelation of both the intellectual and physical elements of collections.”35 By 2015, the IDP team had made 90% of all the collections digitized and made available online for the public. The IPD database unifies dispersed cultural relics in a virtual space and is freely available to people around the world. For lay people who would like to learn about Dunhuang culture, Buddhist scholars, and Chinese people who concern Dunhuang culture as part of their cultural identity, IDP is a handy platform to fulfill multiple roles. The database could be used as an educational tool for people who are interested in art, history, religion, etc., as James Cuno mentions, a tool to disseminate knowledge. Then a question arises: If the digital database, such as IDP, could be used to spread knowledge, could the cultural relics be returned to their original places?

Kate Hennessy, a Trudeau Scholar and doctoral candidate, explores the roles of new technologies in repatriating cultural heritage to originating communities. Museums digitized material culture in museum collections through photos and creating online databases.36 The intangible cultural expression is documented via photographs, videos, and tape recordings into digital files. New technologies allow the originating communities to access images of objects, audio and video recording, texts documenting the material, cultural and linguistic history.37 Visual access to the online collections and cultural heritage by the originating communities, according to Kate Hennessy, is known as “virtual repatriation.” The new media turned the analog of cultural heritage into digital form, facilitating the reconnection of cultural heritage documentation which was once not easily accessible. Also, Kate points out the transformation of cultural heritage from analog into digital form provides the opportunity for “participation in cultural engagement, creative engagement with new media, and forging new possibilities for participatory research and strengthening the relationship between researchers and the community.”38

Since the IDP reunifies the scattered Dunhuang objects and pieces together the historical site, the virtual space, where most of the caves were scanned and digitized, could assimilate the physical space inside the Dunhuang caves. The digital form of the Dunhuang collection reconnects Dunhuang objects and offers an opportunity for the originating community to access and participate in cultural engagement. Chinese people, who are not able to physically visit the caves, can build connections with the site by seeing the collections and the caves remotely. They will get to know the history, aesthetic value, and cultural significance of the relics from the website. Together with the online database, the digital technology allows visitors to immerse themselves in the replica caves, preserve the agency of the caves and build connections between the site with Chinese people, as well as people throughout the world.

Technology in Dunhuang exhibitions

Modern technology, such as 3D printing, Virtual Reality (VR), and Augmented Reality (AR), helps to restore the original setting of the Dunhuang caves and maintain its agency. In May 2016, the J. Paul Getty Museum held a large-scale exhibition titled Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on the Silk Road, commemorating the 25 years collaboration of the Getty and the Dunhuang Academy. The exhibition consisted of three replicated caves— Cave 275 (5th century), Cave 285 (6th century), and Cave 320 (8th century), two of which were made by Dunhuang replica cave maker and shipped from Dunhuang, a 3D visual experience of cave 43, and 43 objects from the Library Cave demonstration.39

The Pure Land AR technology has been applied to exhibitions in Hong Kong International Art Fair 2012, NODEM 2012, and Shanghai Biennale 2012.40 The implementation of Augmented Reality (AR) and spatial user interface allows the visitors to immerse themselves into the computer-generated historical site. Rather than being completely immersed in a synthetic world like a VR-created world, visitors enter a real space with synthetic elements constructed by AR. Digitizing the site not only protects the cave from mass tourism, but also enhances the accessibility of visiting the historical site. First of all, the digitization group scanned the cave and acquired the details and textures of the site. 3D models were made by analyzing raw data, captured by laser scanning. When exhibiting Cave 220, the exhibition walls, which shared the same size as the cave, were covered with “one-to-one scale prints of Cave 220’s wireframe polygonal mesh.”41 This provided the visitors with visual clues of which place to explore. Previously digitized high-solution images of wall paintings and sculptures were projected onto the polygonal mesh, constructing a 3D representation of the cave and sent to the handheld devices. The infrared camera captured the position and the orientation of the visitors. The computers sent out real-time images of the cave structure to the visitors’ tablet in real-time. If people placed the tablet in contact with the wall surface, the images would enlarge into 1:1 scale within the frame of the devices that reveals the finest details of the murals and sculptures.42

The AR technology turned the passive learning experience into an interactive activity and gave the visitors a sense of investigating the real cave. It allows the visitors to reveal the details of the cave and artifacts which they cannot witness with bare eyes. The AR technology enables the exhibition to be displayed and installed at different locations at different times, thus freeing people from the limitations of the physical site’s accessibility.

Conclusion

Today, more and more historical sites are being digitized and are opened to the public who have access to the internet. The International Dunhuang Project is a good example of creating a database for cultural heritage sites. Although IDP is a powerful and useful tool for Dunhuang specialists and researchers, it is not visually appealing and difficult to navigate for laypeople. The IDP homepage lacks images for highlighted artifacts and recommended research categories. If the viewers have no background knowledge of this topic, they are unlikely to know where to start their exploration. To attract more non-specialist viewers, the website should insert highlighted artworks, images, and clear navigation. Also, the database could connect or collaborate with Dunhuang exhibitions. People who visit the exhibitions could search online for more related objects and gain a better understanding of the holistic view of the collection. For the researchers and people who browse the online database, it is helpful to visit the exhibitions that offer an immersive experience of the cave and recreate the original setting for the collections. Therefore, the designer could add a section for links to Dunhuang exhibitions on the IDP page and mention the IDP online database at the exhibitions. By correlating the digitized collections with the physical exhibition space, the collections that have been long lost seem to find their way home. The implementation of modern technology, such as digitization and VR and AR, facilitates the understanding of Dunhuang culture and artifacts, as well as a new way of repatriation.

Notes

-

Whitfield, Roderick, Susan Whitfield, Neville Agnew, Lois Conner, and Wu Jian. Cave Temples of Mogao Art and History on the Silk Road. Los Angeles, Calif: Getty Conservation Institute, 2016. ↩︎

-

Zuozhen Liu, The Case for Repatriating Chinas Cultural Objects (Singapore: Springer, 2016)) ↩︎

-

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Mogao Caves.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed on October, 27, 2021. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440/. ↩︎

-

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Mogao Caves.” ↩︎

-

James Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity?: Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 20 ↩︎

-

Ebin Ma, TEXTILES IN THE PACIFIC, 1500-1900 (ROUTLEDGE, 2017). p8 ↩︎

-

Zouzhen Liu, 868 ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Cuno, 90 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 868 ↩︎

-

Beasley, Sarah, and Candice Kail. “The International Dunhuang Project.” Journal of Web Librarianship 1, no. 1 (2007): 113–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/j502v01n01_09. ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid, 118 ↩︎

-

Whitfield, Susan. “The International Dunhuang Project: A Challenge for Digitization” , vol. 26, no. 1, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1515/mfir.1997.26.1.15, 19 ↩︎

-

Erich Hatala Matthes, “The Ethics of Cultural Heritage,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Stanford University, July 12, 2018), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-cultural-heritage/, 1. ↩︎

-

James Cuno, Whose Culture?: The Promise of Museums and the Debate over Antiquities (Princeton Press, 2009). 2. ↩︎

-

“Lost and Found.” features.thecrimson.com. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://features.thecrimson.com/2013/lost-and-found/. ↩︎

-

“Lost and Found” ↩︎

-

Justin Jacobs, “LANGDON WARNER AT DUNHUANG: WHAT REALLY HAPPENED?,” https://edspace.american.edu/silkroadjournal/wp-content/uploads/sites/984/2017/09/SilkRoad_11_2013_jacobs.pdf, n.d) ↩︎

-

Sanchita Balachandran, “Object Lessons: The Politics of Preservation and Museum Building in Western China in the Early Twentieth Century,” International Journal of Cultural Property 14, no. 01 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1017/s0940739107070014, 24 ↩︎

-

Wen Xing and Zhu Guang, “世纪末追讨敦煌失窃文物,” 华西都市报, accessed October 26, 2021, http://news.sina.com.cn/richtalk/news/culture/9903/032908.html) ↩︎

-

Zuozhen Liu, 5174 ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid, 5244 ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

Ibid, 5303 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 5492 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 5409 ↩︎

-

Ibid ↩︎

-

“Lost and Found.” features.thecrimson.com ↩︎

-

Zuozhen Liu, 2826 ↩︎

-

Shenton, Helen. “Virtual Reunification, Virtual Preservation and Enhanced Conservation.” Alexandria: The Journal of National and International Library and Information Issues 21, no. 2 (2009): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.7227/alx.21.2.4. ↩︎

-

Kate Hennessy, “Virtual Repatriation and Digital Cultural Heritage: The Ethics of Managing Online Collections,” Anthropology News 50, no. 4 (2009): pp. 5-6, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2009.50405.x. 5 ↩︎

-

Kate Hennessy, 6 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 6 ↩︎

-

Wall Paintings at Mogao Grottoes. Accessed October, 10, 2021. https://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/mogao/related_mats.html. ↩︎

-

Chan, Leith Kin, Sarah Kenderdine, and Jeffrey Shaw. “Spatial User Interface for Experiencing Mogao Caves.” Proceedings of the 1st symposium on Spatial user interaction - SUI ‘13, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1145/2491367.2491372. ↩︎

-

Chan, Leith Kin, Sarah Kenderdine, and Jeffrey Shaw. 22 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 22 ↩︎