II. Capturing Complexity: Activating Musical Instruments in Online Museum Collections

- Norman Storer Corrada, The George Washington University

It’s hard to go through a day without musicking in some way. Musicologist Christopher Small proposes music as a verb rather than a noun, and musicking—to music— “is to take part in any capacity in a musical performance”.1 Viewed even more broadly, musicking can be anything from performing a concert in front of thousands of people, to dancing at a party, to listening to the radio, to making a playlist, and beyond. Music is all around us and it is deeply connected to countless dimensions of our lives and cultures. Music also leaves behind countless material traces, including (but by no means limited to) musical instruments. Like all other objects, musical instruments are part of the infinitely complex web of social interactions between humans and things. They contain complex dimensions which include sound, touch, craft, performance, heritage, racism, nationalism, spirituality, and more.

In recent decades, the awareness of these social and material connections has informed the study of musical instruments in organology and ethnomusicology.2 While some museums have applied this approach to curating and displaying musical instrument collections in exhibitions,3 institutions can also embrace these connections within their online information management systems. When used to their full potential, online collections can allow museums to capture the true complexity of objects as social actors by incorporating diverse resources and perspectives and “reconnecting museum objects and knowledge to global flows of culture and information.”4 Building on this idea, this paper explores how museums can use the content included in information management systems and online collection object pages to contextualize musical instruments within the wider social and material networks that they are a part of. By incorporating visual resources, sound and video, and interconnecting multiple types of objects, museums can embrace the inherent complexity of musical instruments within their collections pages and bring those objects to life.

Curating Musical Instruments and Creating Online Museum Collections

Under Western frameworks of knowledge, the study of musical instruments usually falls under the field of organology.5 In the 20th century, organologists were mainly concerned with classifying musical instruments, developing systems such as the commonly used Hornbostel-Sachs classification which divides instruments into families based on how they produce sound. Organologists also explored construction techniques and the historical evolutionary trajectories of instruments. Though much of this work focused on European instruments, organologists also studied instruments from around the world in a process paralleling the systematic study of material culture in museum anthropology, often ignoring Indigenous and non-Western histories, worldviews, and classificatory schemes.6

In recent decades, organologists and, especially, ethnomusicologists7 have pushed for the study of musical instruments to expand beyond classification and lineages and to delve more deeply into the “social life” of musical instruments.8 As Dawe explains,

musical instruments are embodiments of culturally based belief and value systems, an artistic and scientific legacy, a part of the political economy attuned by, or the outcome of, a range of associated ideas, concepts and practical skills: they are one way in which cultural and social identity (a sense of self in relation to others, making sense of one’s place in the order of things) is constructed and maintained.9

This approach is informed by the exploration of active relationships between people and things in anthropology and material culture studies. Although specific theories and terms vary, multiple scholars have sought to highlight that objects are entangled or enmeshed in complex webs of socio-cultural interactions with humans. Within these networks, objects may play multiple roles and attain varying degrees of agency throughout their lives.10 Just like other objects, musical instruments are inextricable from human cultures and their multiple dimensions deserve to be explored.

Some museums with musical instrument collections embrace this perspective when curating physical exhibitions, albeit inconsistently. For centuries, the role of museums was (and too often continues to be) to impose order on the natural and cultural world through white-supremacist, and imperialist hierarchies, disciplinary segmentation, and decontextualization.11 It should be no surprise, then, that many museums have traditionally opted for displaying instruments by following the organological classifications born out of the same Euro-centric frameworks. The permanent displays at more traditional musical instrument museums such as the Museé de la musique in Paris and the Museo degli strumenti musicali in Milan, for example, group instruments based on instrument families and provide relatively little social contextualization. This is often true of museums dealing with Western classical music and instruments, though it is an order also imposed on displays of instruments from musical traditions around the world.

Museums that host collections or exhibitions about popular music tend to explore the social dimensions of musical instruments more extensively by connecting them to artists and wider cultural and historical contexts (see, for example, the Musical Crossroads permanent exhibition at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the David Bowie is temporary exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum12). Curators and designers use various techniques to make popular music exhibitions more engaging and immersive. First and foremost, they draw on multiple kinds of objects (musical instruments, clothing, ephemera, etc.) and connect them to tell a story. Second, many exhibitions use sound and music extensively, either through headphones or out loud. In these cases, sound is afforded the status of object, displayed and working alongside what may be viewed as more obviously material objects.13 Indeed, preserving and sharing sound is an integral part of curating the complex and intriguing totality (“the magic”) of musical instruments.14 Exhibitions also rely on dramatic contrasts and enveloping strategies to capture the viewer’s attention and create an immersive experience, much like music is an experience in itself.15

All these techniques come together in physical exhibitions to show that musical instruments are one component of an incredibly complex network of objects, sounds, people, and relationships tied to all other cultural dimensions. At the same time, the immersive experiences include the visitors and make them part of the story. By embracing complexity and interdisciplinarity, these kinds of exhibitions begin to push (even if too gently) against the traditionally Euro-centric knowledge structures that lie at the core of Western museums. While exhibitions are a powerful and highly visible site in which to challenge these structures and ways of thinking, they are not the only place where museums can highlight the inherent complexity of musical instruments as part of efforts to break disciplinary walls and reconnect objects with their social networks. These connections can also come to life in the collection documentation itself, especially as it appears in museum websites.

Museums are sites of power, and this extends to how they manage their objects and information and make that information accessible online. Erin Canning, writing on the ICOM International Committee for Documentation blog, stated this idea clearly: “[…] information systems – such as collections management systems – are artifacts of systems of power, and like any other system or infrastructure, they enact the power relations of those who originally designed and created the systems to the detriment of those upon whom power is enacted.”16 Information management systems tend to force objects into static hierarchies and classifications that do not reflect their dynamic existence in the world. Additionally, they prioritize only certain forms of knowledge (Euro-centric, colonialist, exclusively text-based, physical, visual, etc.) over others (Indigenous, traditional, oral, multi-sensory, trans-disciplinary, etc.).17 Like all other objects, musical instruments in these collections suffer under the limitations of such a framework, perhaps even exacerbated by their inherent multi-sensory and social function.

To challenge these frameworks, Fiona Cameron highlights the importance of embracing the complexity of networked objects. Cameron and Mengler define complexity as “the holistic, global or non-linear form of intelligibility needed to comprehend a phenomenon” and “a dense, entangled dimension that appears rebellious to the normal order of knowledge.”18 By understanding online collections through this lens of complexity, we can more effectively envision objects connected to one another, to people, and to global flows of materials, information, relationships, and more. Cameron takes this idea further by calling for an ecological view of collections that embraces objects as part of fluid, infinitely complex, and inseparable systems.19 Connecting this view to Tim Ingold’s idea of the meshwork,20 we can imagine each musical instrument object page as a collection of knots tying together all kinds of resources—images, sound, video, etc.—from which we should be able to follow the strings leading to other objects, people, relationships, traditions, cultures, and lives.

Incorporating Visual Resources

Museums tend to prioritize the visual aesthetic component of musical instruments in both displays and online collections pages, often to the detriment of other resources and ways of appreciating and understanding the instruments.21 Nevertheless, incorporating visual resources such as high-quality images, diagrams or schematics of objects, 3D models, and visualizations of entire collections in online information management systems remains a key strategy for institutions to increase access to and better contextualize musical instruments. These resources highlight components of the musical instruments that reflect wider cultural connections, facilitate recreations and artistic reappropriations, and allow users to visualize connections and interactions between instruments (and people). Though rarely, if ever, done, images can also show the instrument in use, interacting with people as it was designed to do. High-quality images of the instruments themselves can even allow users to see detail that may not even be visible in person. Thus, while they should not be prioritized to the detriment of others, these resources are a key component in embracing the complexity of these objects.

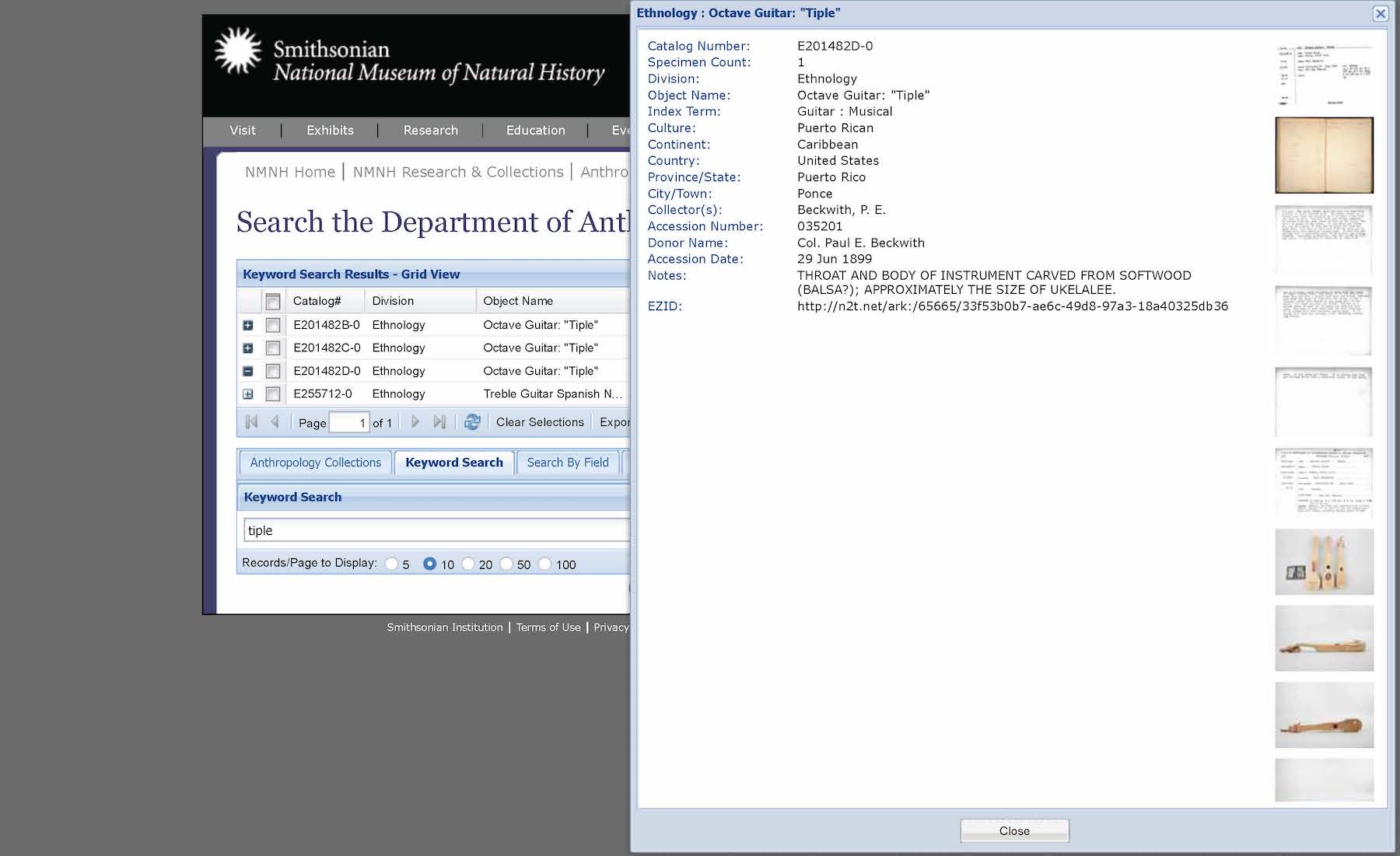

Even when the information about a musical instrument on an object page is extremely limited, a good image can allow craftspeople to recreate an instrument. For example, the National Museum of Natural History page is a simple and seemingly outdated, hardly more than a digital card catalog (fig 1). However, thanks to high-quality images and measurements of a rare 19th century Puerto Rican tiple requinto costero in the collection,22 the luthier William Cumpiano was recently able to create a construction plan and build reproductions of the instrument.23 The object record could do a much better job contextualizing the instrument, but at least the images helped bring them (or a copy) to life.

Visual resources can also go beyond the visible surfaces of instruments, providing a glimpse into more subtle details, construction processes, and even suggesting possible tactile interactions. For example, technical drawing and schematics such as those offered by the Musikmuseet of the National Museum of Denmark and the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston can further aid instrument builders in creating reconstructions. Although in these two examples the drawings exist separately from the object pages, they are a resource that could be integrated to add an additional visual dimension.

As another example, the Smithsonian Institution Digitization Program Office’s 3D Program has digitized two musical instruments associated with well-known artists: Charlie Parker’s alto saxophone in the National Museum of African American History and Culture24 and José Feliciano’s guitar in the National Museum of American History.25 The 3D scans of the objects allow viewers to see colors and textures in a context that more closely resembles a physical object. Furthermore, users can explore angles that aren’t necessarily visible in photographs. The resolution of the scans can make viewing certain details difficult, and users cannot currently view inside the instruments. However, projects such as the Musical Instrument Computed Tomography Examination Standard (MUSICES) at the Germanisches National Museum which are developing technology and standards to produce more detailed 3D models could make such features available in the future.26

Museums can also use data visualization to help us see the complex networks that instruments in their collections are enmeshed in.27 The Musical Instrument Museum of the University of Leipzig (MIMUL) musiXplora app allows users to visualize connecting lines between objects in their collections.28 The website features visual maps of places, time, people, objects, and more. Although still in its infancy and limited to European instruments (and especially keyboards), the resource is an example of embracing complexity and highlighting instruments as part of an entire ecosystem. Another innovative example of data visualization in a music exhibit is the Library of Congress Southern Mosaic online exhibit. The exhibition includes a visual map that gracefully and effectively represents the humans, geographies, genres, and interconnections of the LOC collection of Lomax field recordings of Southern music.29 Similar mapping could be used to re-incorporate musical instrument collections into the flows of music and culture.

Incorporating Sound and Video

Musical instruments are made to interact with humans to produce sound, and this unique purpose highlights the need of preserving and sharing that sonic component. The sound of the instrument can be treated as its own object worthy of preservation.30 As Eric De Visscher explains, “the sound object is not just a quality or an attribute of the object—it’s not like the color of the object, if you want, because it exists independently also—but both A, the object, and B, the sonic object, are part of a whole of this kind of hidden real object.”31 By incorporating sound as part of information management systems, museums can also move beyond exclusively visual sources of analysis.32

When an instrument is in playable condition, its object page can include recordings of the actual instrument. For example, the Musical Instrument Museums Online (MIMO) page for an eighteenth-century guitar in the Musée de la musique, Paris,33 features several audio clips of music played on that same guitar. If instruments cannot be played, a recording of a similar instrument can be featured instead. On the object page of a nineteenth-century Peruvian charango in the MFA Boston collection,34 the museum included an audio recording of Bolivian musician Hector Martínez-Morales playing a piece on a different charango in the 1990s. Although a different instrument, the recording nonetheless highlights the sonic dimensions of the collection instrument. Additionally, in both collections, searches can also be filtered based on the availability of audio (and video) resources.

Audio recordings don’t have to be limited to music. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) includes recorded curatorial commentary on a handful of instruments on display, in addition to recordings of the instruments themselves (see the page for the Cristofori piano).35 Audio resources can also capture oral histories, conversations about traditions and uses of the instruments, discussions with artists about what their instruments mean to them, rich descriptions of the physical features of instruments for those who are blind or visually impaired, and so on.

Streaming services can also allow museums to incorporate audio resources, especially commercial music recordings. The Met has produced several Spotify playlists associated with their musical instrument exhibitions (such as a playlist accompanying the Play it Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll temporary exhibit) or which contain tracks that use instruments in the collection (like “Archtop guitar at The Metropolitan Museum of Art”). Unfortunately, while the museum does feature the playlists elsewhere on their website (for example, on the Play it Loud page), individual instrument object pages do not link to them. Furthermore, because the playlists are published on Spotify by Met curator Jayson Kerr Dobney rather than by The Met itself, they are harder to locate for anyone interested in them, ultimately hindering their purpose.

Museums can also include video resources as an integral part of their object pages to show not only sound but also the instruments in action. When made available by the contributing institutions, the Musical Instruments Interface for Museums and Collections (MINIM) UK, for example, includes videos as part of the information that accompanies many musical instruments (like this pair of kettledrums).36 These often feature musicians playing the instruments and allow us to see and hear the instruments as working objects designed to interact with people.37 We can see instruments in their proper positions relative to the human body and get a sense of their tactile interfaces. Additionally, like with audio resources, videos are an opportunity to include resources about instrument construction, artists, performances, traditions that may otherwise be missing in text-based information on object pages.

Even if it is not immediately feasible for some museums to embed videos in their information systems, institutions could take advantage of their existing resources on video hosting sites by using hyperlinks. The Met’s YouTube channel features a playlist called MetMusic dedicated to their musical instrument collection. In it, they post videos of musicians playing instruments in the collection or similar to examples in the collection. Additionally, some of the videos feature interviews with curators and/or performers in which they discuss the history and social contexts of some of the instruments. For example, a video featuring Puerto Rican cuatro player Fabiola Méndez shows several Puerto Rican string instruments in The Met’s collection in action. Méndez also adds historical context and her perspective as a musician and educator.38 These videos are a good example of content that can bring instruments to life by showing them in use and highlighting their complexity and relationships. Although it is not the case with the Fabiola Méndez video, many of the other videos on the channel link back to relevant objects in the descriptions. However, the pages of instruments featured in the videos do not link to them, missing the opportunity to enrich the available information with existing content.39

Connecting Objects

In addition to an extensive musical instrument collection, The Met, like other so-called encyclopedic museums, also holds a vast repository of other kinds of objects: visual art, textiles, historical objects, archaeological artifacts, ethnographic collections, etc. Because of this, encyclopedic museums are well-equipped to explore the complex social dimensions of their musical instruments by drawing connections between these and other kinds of related (though not necessarily musical) objects. Curators of The Met’s updated Musical Instruments gallery were aware of this and made an effort to incorporate objects from other departments to better contextualize instruments.40

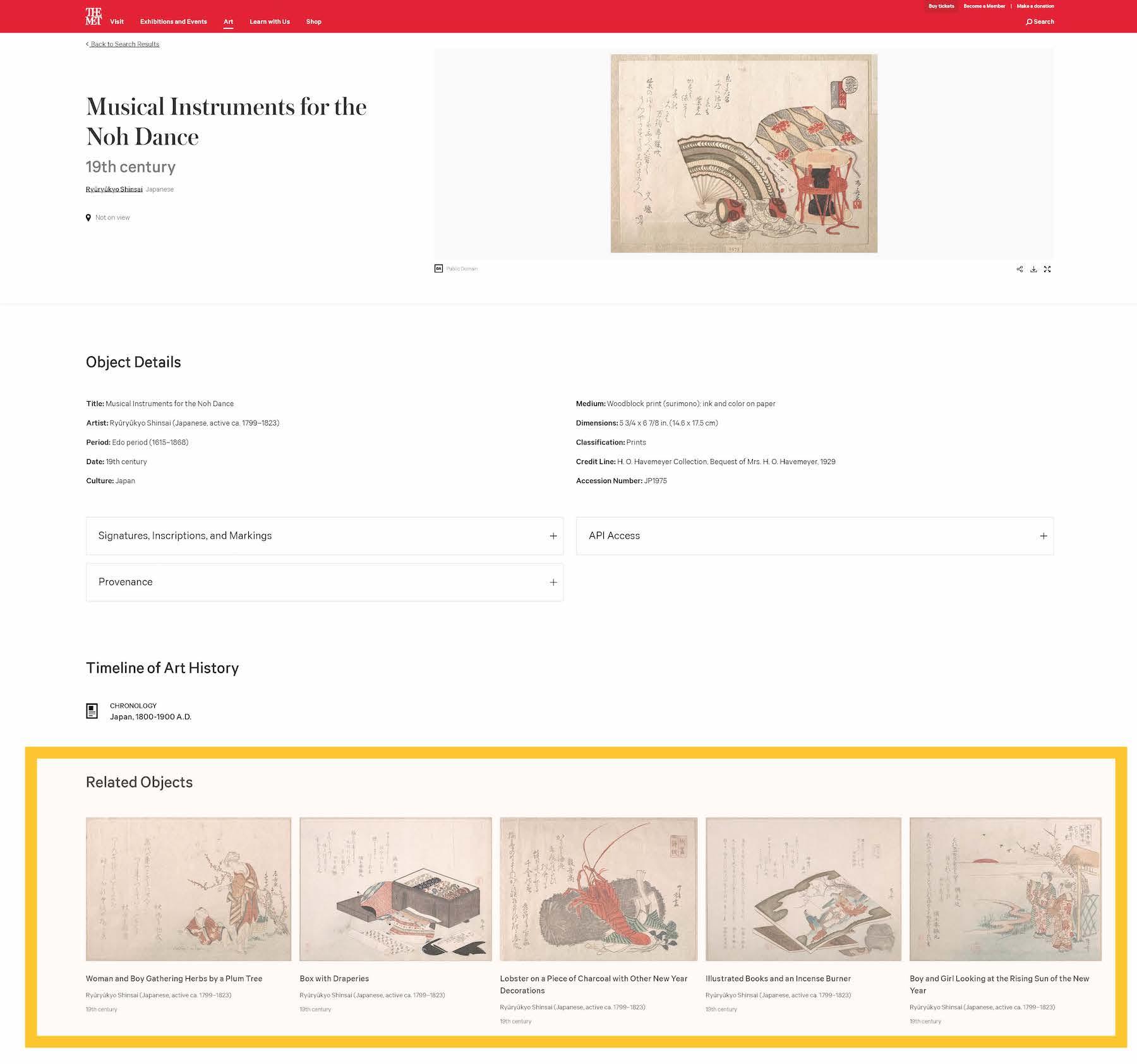

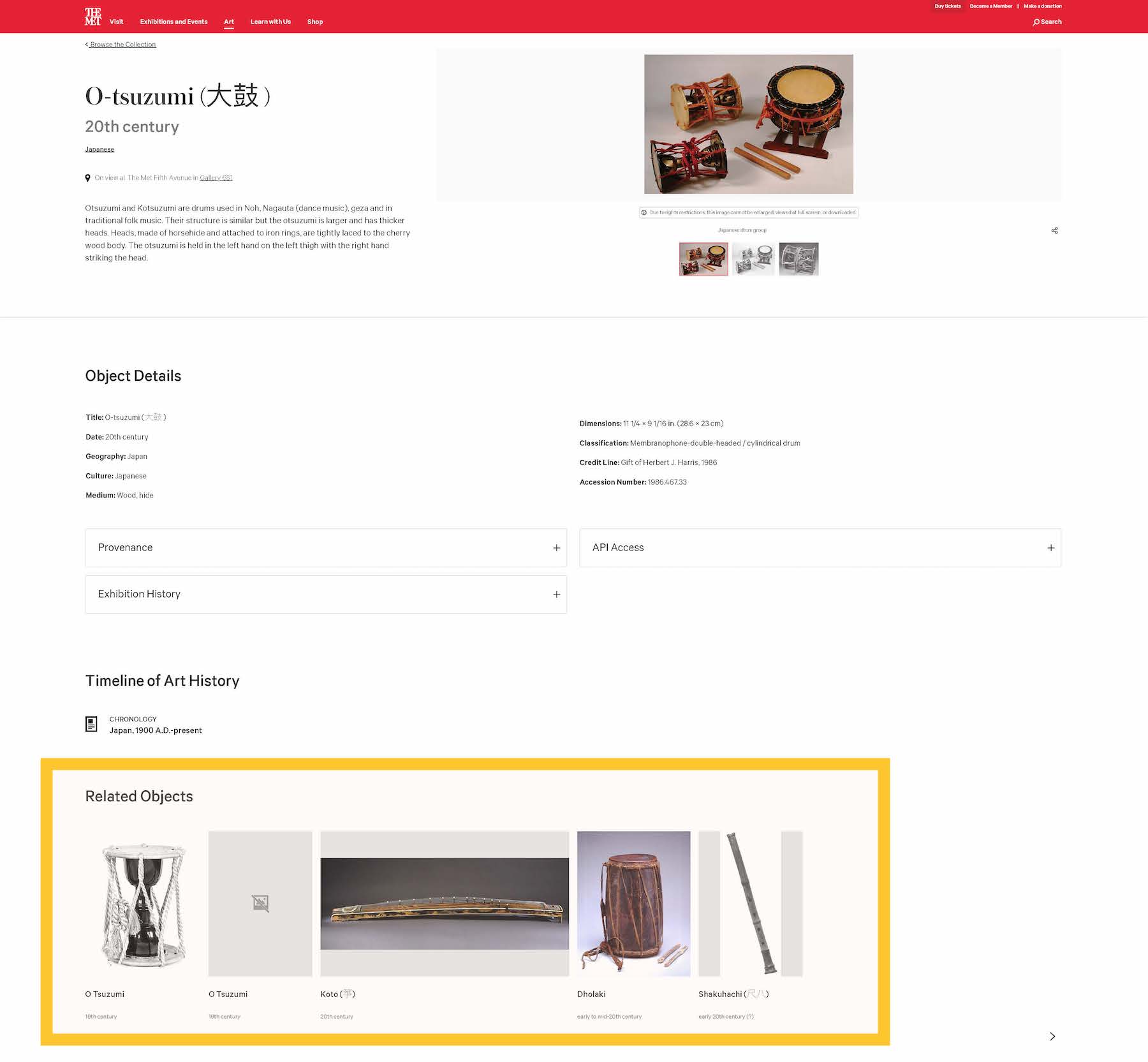

However, when it comes to online content, despite hinting at these connections at the collections search level, The Met and other museums often miss the chance to highlight these relationships within specific object pages. For example, the page for a woodblock print by Japanese artist Ryūryūkyo Shinsai titled “Musical Instruments for the Noh Dance,”41 which depicts two drums in addition to a fan, a textile, and a scroll, displays prints by the same artist in the related objects section but no musical instruments (fig 2). When searching “Noh drum” on the website,42 one can find at least five drums and seven other related objects. Unsurprisingly, the object page for one set of three drums43 did not display any relationship to the print or other artworks depicting similar instruments (fig 3).

By not highlighting the relationship between these objects, The Met is missing a valuable opportunity to enrich the information available for each one while inviting visitors to explore other parts of the collection. I am not saying object pages should identify or link to every single related item in the museum’s collection. Indeed, the question of how to best display these relationships is a constantly evolving issue for The Met as well as countless institutions and museum technologists.44 Nevertheless, these missed opportunities highlight the limitations of hierarchical and disciplinarily disconnected methods of organizing information management systems. Because the drums are in the Musical Instruments department and the print is in the Asian Art department, the objects exist separate from each other in the museum and online. Ideally, the physical obstacles that make such crossovers difficult in the real world should not be as pressing virtually.

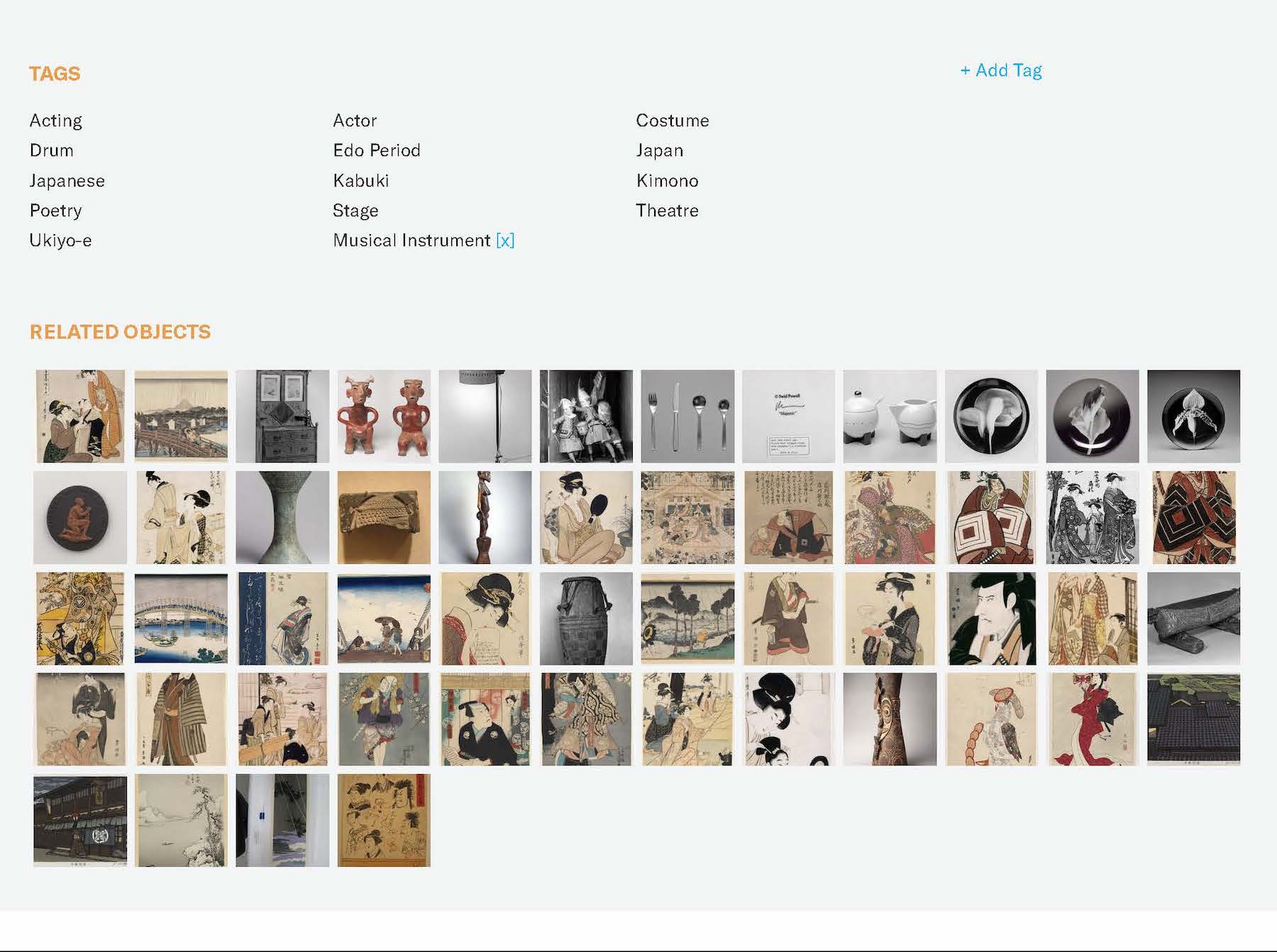

To tackle this challenge, the Brooklyn Museum allows users to create tags on different objects to connect them and generate what is known as folksonomies (folk taxonomies). This non-hierarchical, responsive, dynamic strategy can draw on the knowledge, insights, and experiences of users to highlight complexity within collections. To mirror the previous example from The Met, on the page for the 1803 woodblock print “The Actors Matsumoto Yonesaburo and Segawa Kikunojo” by Japanese artist Utagawa Toyokuni I,45 which features a tsuzumi drum used in Noh and Kabuki performances, we can see a series of related objects ranging from prints by the same artists, to Japanese furniture, to various drums, all connected through both user- and curator- generated tags (fig 4). Unfortunately, the Brooklyn Museum collection does not include a tsuzumi, but it is likely that if such a drum were in the collection, it would appear in the related objects list.

While still requiring some curator involvement, drawing on user-submitted tags can make it somewhat easier for the website to connect related objects without requiring more hours of labor from museum staff. Though not without their own set of limitations, challenges, and concerns, folksonomies contribute to a more dynamic use of the collection and the online musical instruments by users.46 Moreover, their decentralized and democratic approach challenges the authority of hegemonic systems of knowledge, redistributing authority to various publics, embracing different ways of knowing, and capturing more complex perspectives and relationships.47

Conclusion

Images, models, diagrams, visualizations, audio recordings, videos, and interconnected objects can work together to capture the events, ecosystems, relationships, and complex human-object interactions that should be evident in online collections. These resources and strategies must be understood as part of a whole. They are pieces in a complex and ever-changing dynamic bundle of connections that form musical instruments, and they must work together with other types of resources to activate multiple senses and ways of understanding, feeling, experiencing, thinking.

Funding and logistical barriers often keep institutions from providing all these resources at once, but we can imagine these strategies working together to contextualize musical instruments as richly and completely as possible. Changing how online collections are presented to the public requires time, effort, and funding. As institutions improve online collections to make full use of often existing resources, they will continue to move their information management systems beyond the narrow structures that limit them today. In doing so, they will come closer to capturing the complexity and the magic of musical instruments.

Notes

-

Christopher Small, “Musicking — the Meanings of Performing and Listening. A Lecture,” Music Education Research 1, no. 1 (March 1, 1999): 9–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380990010102. ↩︎

-

Eliot Bates, “The Social Life of Musical Instruments,” Ethnomusicology 56, no. 3 (2012): 363–95, https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.56.3.0363; Kevin Dawe, “People, Objects, Meaning: Recent Work on the Study and Collection of Musical Instruments,” The Galpin Society Journal 54 (2001): 219–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/842454; Kevin Dawe, “The Cultural Study of Musical Instruments,” in The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction, ed. Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert, and Richard Middleton, 2nd ed. (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011), 195–205, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gwu/detail.action?docID=957262; Henry Johnson, “An Ethnomusicology of Musical Instruments: Form, Function, and Meaning,” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 26, no. 3 (January 1995): 257–69; P. Allen Roda, “Toward a New Organology: Material Culture and the Study of Musical Instruments – Material World,” Material World (blog), November 21, 2007, https://materialworldblog.com/2007/11/toward-a-new-organology-material-culture-and-the-study-of-musical-instruments/; John Tresch and Emily I. Dolan, “Toward a New Organology: Instruments of Music and Science,” Osiris 28, no. 1 (2013): 278–98, https://doi.org/10.1086/671381. ↩︎

-

Sarah Baker, Lauren Istvandity, and Raphaël Nowak, “The Sound of Music Heritage: Curating Popular Music in Music Museums and Exhibitions,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 70–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1095784; Sarah Baker, Lauren Istvandity, and Raphaël Nowak, Curating Pop: Exhibiting Popular Music in the Museum (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019); Alcina Cortez, “The Digital Museum: On Studying New Trajectories for the Music Museum,” MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016, March 2, 2016, https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/the-digital-museum-on-studying-new-trajectories-for-the-music-museum/. ↩︎

-

Suse Anderson, “Some Provocations on the Digital Future of Museums,” in The Digital Future of Museums: Conversations and Provocations (London: Routledge, 2020), 20, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429491573. ↩︎

-

Johnson, “An Ethnomusicology of Musical Instruments: Form, Function, and Meaning.” ↩︎

-

Dawe, “The Cultural Study of Musical Instruments.” ↩︎

-

Ethnomusicology is the anthropological study of music, or the study of music as culture. For an introduction to ethnomusicology, see Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Soundscapes: Exploring Music in a Changing World, Third Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015). ↩︎

-

Bates, “The Social Life of Musical Instruments.” ↩︎

-

“The Cultural Study of Musical Instruments,” 195. ↩︎

-

Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819582; Ian Hodder, Where Are We Heading?: The Evolution of Humans and Things (Yale University Press, 2018); Tim Ingold, Redrawing Anthropology: Materials, Movements, Lines (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2011); Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford University Press, 2005); Daniel Miller, ed., Materiality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005). ↩︎

-

Anderson, “Some Provocations on the Digital Future of Museums”; Tony Bennett, “The Exhibitionary Complex,” in Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory, ed. Nicholas B. Dirks, Geoff Eley, and Sherry B. Ortner, vol. 12 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994), 123–54, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691228006-006; Fiona Cameron and Sarah Mengler, “Complexity, Transdisciplinarity and Museum Collections Documentation: Emergent Metaphors for a Complex World,” Journal of Material Culture 14, no. 2 (June 1, 2009): 189–218, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183509103061; Fiona Cameron and Sarah Mengler, “Activating the Networked Object for a Complex World,” in Handbook of Research on Technologies and Cultural Heritage: Applications and Environments, ed. Georgios Styliaras, Dimitros Koukopoulos, and Fotis Lazarinis (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2010), 166–87. ↩︎

-

Kate Bailey, Victoria Broackes, and Eric de Visscher, “‘The Longer We Heard, the More We Looked’ Music at the Victoria and Albert Museum,” Curator: The Museum Journal 62, no. 3 (2019): 327–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12334. ↩︎

-

Bailey, Broackes, and de Visscher; Alcina Cortez, “Performatively Driven: A Genre for Signifying in Popular Music Exhibitions,” Curator: The Museum Journal 62, no. 3 (2019): 343–66, https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12330. ↩︎

-

Eric de Visscher, “Sonic Objects in Museums: A Philosophical Turn” (MINIM UK Digital Humanities and Musical Heritage Workshop, Royal College of Music, London, July 2, 2018), https://youtu.be/wa19gwcxa8o. ↩︎

-

Cortez, “The Digital Museum”; Cortez, “Performatively Driven.” ↩︎

-

Erin Canning, “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems,” ICOM CIDOC (blog), August 2020, https://cidoc.mini.icom.museum/blog/making-space-for-diverse-ways-of-knowing-in-museum-collections-information-systems-erin-canning-august-2020/. ↩︎

-

Anderson, “Some Provocations on the Digital Future of Museums”; Canning, “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems.” ↩︎

-

“Activating the Networked Object for a Complex World,” 171. ↩︎

-

Fiona R. Cameron, The Future of Digital Data, Heritage and Curation: In a More-than-Human World (Routledge, 2021). ↩︎

-

Ingold, Redrawing Anthropology. ↩︎

-

Canning, “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems.” ↩︎

-

“Octave Guitar: ‘Tiple’,” 1898-99, catalog number E201482D-0, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, http://n2t.net/ark:/65665/33f53b0b7-ae6c-49d8-97a3-18a40325db36. ↩︎

-

Néstor Murray-Irizarry, “Renace un olvidado tiple requinto costero puertorriqueño de 1898,” El Adoquín Times, September 30, 2021, https://eladoquintimes.com/2021/09/30/renace-un-olvidado-tiple-requinto-costero-puertorriqueno-de-1898/. ↩︎

-

“Alto saxophone owned and played by Charlie Parker,” ca. 1947, object number 2019.10.1a-g, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, http://www.3d.si.edu/object/3d/alto-saxophone-owned-and-played-charlie-parker%3Ac7c58ff8-fd1f-4cf6-9813-6bca3cd0b8b3. ↩︎

-

“Concerto Candelas Guitar, played by Jose Feliciano,” 1967, ID number 2018.0136.01, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, https://3d.si.edu/object/3d/concerto-candelas-guitar-played-jose-feliciano%3A44c59cb6-97d4-4818-878e-26bfafdd004b. ↩︎

-

Frank Bär, “MUSICES, and 3D Scanning of Instruments” (MINIM UK Digital Humanities and Musical Heritage Workshop, Royal College of Music, London, July 2, 2018), https://youtu.be/wrlcFDswF3E; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, “MUSICES,” Germanisches Nationalmuseum, accessed November 23, 2021, https://www.gnm.de/en/research/research-projects/musices/. ↩︎

-

Maxene Graze, “Museums Are Going Digital-and Borrowing from Data Viz in the Process,” Nightingale (blog), September 1, 2020, https://medium.com/nightingale/museums-are-going-digital-and-borrowing-from-data-viz-in-the-process-b5e3828b4000. ↩︎

-

Heike Fricke, “The Research Center Digital Organology at the Musical Instruments Museum Leipzig” (2021 Meeting of the American Musical Instrument Society, Virtual, June 4, 2021), https://youtu.be/q-1xS_Y14rU. ↩︎

-

Aditya Jain, “Southern Mosaic,” Southern Mosaic, 2018, https://adityajain15.github.io/lomax/. ↩︎

-

Eric de Visscher, “Sound in Museums Part 3: Ten Golden Rules by Prof Eric De Visscher,” V&A Blog (blog), May 11, 2018, https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/projects/sound-in-museums-part-3-ten-golden-rules-by-prof-eric-de-visscher. ↩︎

-

de Visscher, “Sonic Objects in Museums: A Philosophical Turn.” ↩︎

-

Canning, “Making Space for Diverse Ways of Knowing in Museum Collections Information Systems.” ↩︎

-

“Guitare,” ca. 1780, inventory number E.997.3.1, Musée de la musique, accessed through MIMO International, https://mimo-international.com/MIMO/doc/IFD/OAI_CIMU_ALOES_0158844. ↩︎

-

“Lute (charango),” 19th century, accession number 17.2241, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/50812/lute-charango. ↩︎

-

Bartolomeo Cristofori, “Grand Piano,” 1720, accession number 89.4.1219a–c, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/501788. ↩︎

-

“22-inch kettledrum,” 19th century, inventory number 2863, University of Edinburgh, accessed through MINIM UK, http://minim.ac.uk/index.php/explore/?instrument=29069. ↩︎

-

Chris Caple, “In Working Condition,” in Conservation Skills (London: Routledge, 2000), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203086261. ↩︎

-

The Met, “Fabiola Méndez, Cuatrista,” YouTube, October 15, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0U3fP0tZyY&list=PLB73DA5433C3A8C95&index=1. ↩︎

-

Efrain Vega, “Cuatro,” 1995, accession number 2004.395.1a–c, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503759; Luis Ángel Colón, “Tiple Puertorriqueño,” 2002, accession number 2003.216.2, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503622; Luis Ángel Colón, “Cuatro Puertorriqueño,” 2002, accession number 2003.216.1, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503621. ↩︎

-

Pac Pobric, “How The Met Is Presenting a New Global Narrative for Musical Instruments,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 18, 2018, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/collection-insights/2018/musical-instruments-art-of-music-through-time-interview. ↩︎

-

Ryūryūkyo Shinsai, “Musical Instruments for the Noh Dance,” 19th century, accession number JP1975, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54560. ↩︎

-

There are three types of drums used in the hayashi ensemble which traditionally accompanies Noh performances: the tsuzumi or kotsuzumi, the ōtsuzumi, and a small taiko. See David W. Hughes, “Tsuzumi,” in Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press, September 22, 2015), https://doi-org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.L2286359. ↩︎

-

“O-tsuzumi (大鼓 ),” 20th century, accession number 1986.467.33, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/504426. ↩︎

-

Elena Villaespesa, Madhav Tankha, and Bora Shehu, “The Met’s Object Page: Towards a New Synthesis of Scholarship and Storytelling,” MW19: MW 2019, January 15, 2019, https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/the-mets-object-page-towards-a-new-synthesis-of-scholarship-and-storytelling/. ↩︎

-

Utagawa Toyokuni I, “The Actors Matsumoto Yonesaburo and Segawa Kikunojo,” ca. 1803, accession number 16.534, The Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/9784. ↩︎

-

Neal Stimler, Louise Rawlinson, and Andrew Lih, “Where Are The Edit and Upload Buttons? Dynamic Futures for Museum Collections Online,” MW19: MW 2019, April 4, 2019, https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/where-are-the-edit-and-upload-buttons-dynamic-futures-for-museum-collections-online/. ↩︎

-

Susan Cairns, “Mutualizing Museum Knowledge: Folksonomies and the Changing Shape of Expertise,” Curator: The Museum Journal 56, no. 1 (January 2013): 107–19; Cameron and Mengler, “Complexity, Transdisciplinarity and Museum Collections Documentation.” ↩︎