XI. Digitizing Cultural Heritage Sites: Historical Context, Current Realities and Future Possibilities

- Laura Dickson

Why preserve cultural heritage sites? There have been many stories in the news in recent years about tragedy, natural or otherwise, destroying or severely damaging places of historical value. In response, there have been enormous efforts to preserve these sites in some way. In some cases, that means physically restoring the structures of the site, while for others, the sites have been so irrevocably destroyed that some preservative means other than physical restoration are needed. In both scenarios, some accounting of the original site is needed. The answer to this problem has been, in many cases, site digitization projects, where photographs, laser scans and other forms of digital data are used to create a digital representation of the space. Undertaking this act of digital recreation, though, begs the question – once the data has been created and processed, how will it be used in the future? By recreating it digitally, the project declares the site to have intrinsic value that makes it a vital piece of cultural heritage, but by that very action has removed it from its traditional physical context. This can reinforce the impacts of colonialism, by removing these important places from the control of the people who created them, denying them access to their own cultural heritage. In order to best care for these digital objects and the cultural heritage they carry, it is vital to be mindful of the realities of digital objects, and recognize that they are not the same as those of physical ones. To do this, it is critical to devise new means to ensure that these digital creations are used in a way to benefit their source communities.

What Is a Cultural Heritage Site and Why Are They Important?

The first question to ask when considering how these sites are treated is how sites become recognized as part of a culture’s heritage. According to Article 1 of United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s Convention Concerning the Protection of the World, Cultural and Natural Heritage, a cultural heritage site is a manmade place (fully or in significant proportion) that has either historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological value. Though UNESCO only extends this definition to sites of “outstanding universal value,”1 in this paper I expand it to include sites of intrinsic value to their source communities, in order to better explore the intersection between neo-colonial attitudes of worth and the creation and implementation of site digitization projects.

Who, then, are the source communities for these sites? Most times, the source communities are the people who originally created and have used these sites, or direct descendants thereof. However, some cultural heritage is ancient enough to predate the culture or nation whose territory currently encompasses it, such as Palmyra (built in the 2nd century BCE2, but resides in Syria, which became a country in 19463). Therefore, a more useful definition of a source community for this subject is the most recent community to consider it a vital part of their cultural heritage, or to commit to caring for the site.

Heritage is instrumental to community identity-making. For displaced communities, it allows members to maintain links to their homeland, while building a meaningful future in their new home. For oppressed communities, it allows them to maintain their sense of identity in the face of external societal pressures.4 These physical sites of heritage and the land they stand on are not only active parts of the everyday lives of many communities, but are the basis for much of their tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Indigenous communities, for example, often express their cultural heritage through their relationship to the land around them, with the landscape itself taking a vital, necessary role in passing down their culture to the next generation. Conversely, immigrant communities find meaning in their own stories by embracing the dominant narrative of the culture to which they have migrated, finding a way to weave in the heritage they bring with them into that narrative, making themselves a part of the source community.5 Since cultural heritage sites play such a critical role in how their source communities perceive themselves, these projects have the ability to greatly impact how they construct their identity and interact with their heritage for years to come.

What Challenges Do These Sites Face That Put Them at Risk?

Considering the significant role these sites play in communities’ lives and identities, many provisions for monitoring and protecting them have been put into place, such as Article 11 of UNESCO’s convention on world heritage.6 But, as mentioned previously, this convention only provides guidelines for the protection of sites perceived to have universal value. This means that for cultural heritage sites which have not received this designation, individuals and organizations which seek to digitally preserve them will need to be aware of the factors which can endanger them and keep watch on those at greatest risk, since there is no outside organization monitoring their status.

There are many factors which can put a site at risk that need to be accounted for when considering a digitization project; some can be remedied, others are foreseeable, and still others can happen before any measures can be taken.

Natural disasters, such as the earthquake which decimated Kathmandu in Nepal,7 and the ongoing threat of climate change will impact both the physical needs of cultural heritage sites as well as the community around them.8 Such events can cause damage that may be repaired or restored using the data generated by these projects. This data can also be used in preventative restoration work in anticipation of damage done by such factors, such as the work being done at the Thomas Jefferson Memorial. Though the site is not in immediate danger of destruction, its managers brought in CyArk, a non-profit organization dedicated to digitally recording cultural heritage, to document the site to provide a baseline against which they can measure future restorative efforts. This allows them to better understand how to care for the site, as well as improve their documentation of changes the structure experiences over time.9

Similarly, societal factors can play a somewhat predictable role in the increasing risks some sites face. For instance, social upheaval like the civil war in Syria,10 conflicting business interests like those that resulted in the destruction of a Mayan pyramid in Belize,11 and governmental neglect or deprioritization such as what occurred to the National Museum of Brazil12 and the current land sales approved by the government in the Southwest United States13 can all factor into heightened risk for sites. Finally, there is the ever-present risk for unforeseeable accidents, such as the fire which consumed Notre Dame Cathedral in 2018.14

While some of these factors can put cultural heritage sites at greater and more immediate risk than others, all must be taken into consideration when choosing what to digitize. Such a decision can determine the site’s fate in the long term; whether the project will be preservative, protecting the site for the future, or restorative, recreating the site following significant damage or complete destruction.

How Does a Site Become Digitized?

There are two main methods by which site digitization projects create their digital models: photogrammetry and LiDAR. Photogrammetry uses photos taken of the site or structure from a variety of angles to generate a 3D digital model. These photos can be taken from a variety of sources (from a smartphone to a high-end camera attached to a drone), but in order to create a rendering of the site, the program needs many photographs from dozens of angles. The highest-quality renderings need 360° coverage of the site or structure, which can take hundreds to thousands to millions of photos to create, depending on the size of the site.15 LiDAR, in contrast, uses laser scanning to calculate the distance between a central machine and anywhere from millions to billions of locations throughout the structure, which can then be turned into a digital representation of that structure.16 While they can be used separately, if combined, these two techniques can create a 3D model of the site accurate enough to measure the cracks in the bricks of a structure.17 These digital objects can then be used in a variety of ways, from digital display to 3D printing to structural analysis; the limit is not the data, but rather how people can conceive of using it. The fact that it is digital data, though, means that it requires an interface in order to experience or interact with it in a meaningful way; the gatekeepers stop being those who control access to the physical site, and become those which control access to the digital one.

Who Chooses What Gets Saved?

With so many sites in danger of destruction around the world and such limited resources available to preserve them, the managers of these site digitization projects must make judgement calls on where to spend their time. UNESCO provides the means for identifying threats to cultural heritage sites, as well as the procedures for combating them in Article 4 of its convention on world heritage.18 However, this convention leaves little guidance for sites which have not been declared world heritage sites. In the absence of this monitoring, each site digitization organization has created their own criteria to determine where they should focus their efforts next, which has led to two distinct kinds of project foci – preventative and restorative.

Preventative Work Vs. Restorative Work

Site digitization projects tend to come about due to one of two instigating factors; either a request for assistance from the organization in charge of the site, or a surge of public support, usually due to media coverage of a tragedy that has befallen the site. The purposes of these projects then fall into two categories: preventative, where the work is done in order to prevent or repair damage likely to befall the site from foreseeable forces, and restorative, where the work is done to restore or recreate a site that has been damaged or destroyed suddenly. Each type of project has its advantages, as well as its restrictions.

Preventative projects have the widest range of possibilities in terms of what they can produce. Often these projects start at the request of the organization that controls the cultural heritage site. This means that the project staff is given access to the site before a destructive event occurs, and the time to take the in-depth measurements to create models of significant quality to aide with restoration work, or be used as a scientific reference.19 However, these priorities are set by the site managers, who might not necessarily be members of the source community. For instance, when Bears Ears National Monument was created, there was a conscious effort to include the source community of the cultural heritage within the monuments’ bounds in decision making about how the site would be used. A year later, though, the federal government, who is legally in charge of the monument, began the process to reduce the protections on the site over the objections of the indigenous communities whose ancestors had created the cultural heritage sites there.20 While this situation may not be the case for every cultural heritage site, it shines a light on how easy it can be to reinforce oppressive power structures when source communities do not have the power to control how their sites are used.

Restorative projects are usually restricted to very specific site reproductions. Since these projects tend to be initiated once a site is destroyed (or at least made unsafe or impossible for the public to access), the project scale is limited to what has already been documented at the site. Due to the limits of crowdsourcing, it is also limited to what images people are willing to donate and the quality and quantity of what is donated.21 In order to increase the quality of what they produce, then, these projects need to focus on the effectiveness of their outreach to attract more contributors, and hopefully acquire the information they need. However, these projects are not limited by what they have current official access to; so long as people are willing to donate images of the site, the reconstruction can continue. Like preservative projects, though, control over these projects may not rest with the source community; anyone can start such a project with a website, data storage, and the right software.

A weakness of both types of projects is their need for vast amounts of data. The raw data collected from the Thomas Jefferson Memorial project undertaken by CyArk, for example, takes nearly 284 GB to store.22 In order to control and process this data in a meaningful way, those seeking to use it must have the technological capacity to maintain the data in the long term, manipulate it into a meaningful format (such as a 3D model) and create an interface for their target audience to interact with the data or end product (such as a website). This means that these projects are generally limited to sites with either significant tourist traffic (as likely only a portion of which will end up donating their photographs or donating to the cause), or the institutional resources to bring in the equipment necessary to undertake this sort of project.

State of the Field

In order to understand the impact site digitization projects can have, it is helpful to examine some existing cases to see how they get their data, how have they used it and how are they managing it. This paper will therefore explore four case studies, including projects which seek to create digital objects from multiple sites in order to preserve cultural heritage en masse, and those which focus on preserving only a single site, to better understand the state of the field. Like the digitization projects that museums use to digitally record their own collections,23 these projects create digital representations of the objects in their care. Through that lens, it is possible to gain insight into how these digital objects might also be treated.

Restorative Projects

Restorative projects seek to recreate and, in some way, restore cultural heritage that has been destroyed. While on rare occasion there may have been some preventative digitization done at the site before the precipitating event, in most cases organizations which seek to create digital models of destroyed sites must gather the data they need from crowdsourcing projects.

The #NEWPALMYRA project was originally started by activist Bassel Khartabil to create 3D digital reproductions using photogrammetry of the structures of the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. While this started in 2005 as a personal project, it grew into an effort that crowdsourced photographs from around the world as many of these sites were occupied or destroyed by ISIS in 2015.24 Though Bassel Khartabil was imprisoned and executed by the Syrian regime, the online community which contributed to his work continues to do so to bring greater awareness to the struggles of the Syrian people.25 In response to the fire at Notre Dame, the project has expanded to make the software they use to create their models available to other cultural heritage preservation projects.26 Similarly to the #NEWPALMYRA project, what was originally known as Project Mosul began as a response from Matthew Vincent and Chance Coughenour to the destruction of the Mosul Museum in Iraq as they sought to recreate a gallery of cultural heritage objects that ISIS destroyed. Like #NEWPALMYRA, another tragedy affecting a heritage site (in this case, the 2015 earthquake in Nepal) transitioned Project Mosul into Rekrei at the request of its contributors, expanding its scope to include other at-risk cultural sites around the world.27

The strength and the weakness of these crowdsourced efforts is community input. So long as their community is willing to donate photographs, time and money, the scope appears endless; and since they both profess to be open-source, what they create is available for everyone to use. This means, though, that there is no oversight in how the data is used, nor any mechanism by which source communities can hold them accountable. For now, current projects which use these models appear focused on creating sympathy for their source communities and inspiring action on their behalf,28 but there is nothing in place to safeguard this digital heritage from misuse, however unintended.29

Preventative Projects

There are a number of current digitization projects around the world seeking to document and preserve cultural heritage, not just in case of disaster, but to actively prevent its destruction. Many of the organizations carrying out this work are non-profits, but which often work in concert with for-profit and government agencies to complete their projects.

CyArk was created in 2003 by Ben and Barbara Kacyra in response to the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. This company works to “digitally record, archive and share the world’s most significant cultural heritage”. They also work to train members of the source community to document their own heritage, particularly when it is threatened by forces such as social upheaval like in the case of Project Anqa, where Syrian professionals were trained by CyArk so that they could document cultural heritage sites at risk of being damaged by the ongoing civil war.30 Unlike the previously mentioned projects, they use both photogrammetry and LiDAR to produce high-resolution imagery that can be combined into a single model, and also collaborate directly with the organizations managing the sites to gain the access they need for their work.31 Those projects produced in conjunction with other agencies tend to have restricted public access due to security or privacy concerns.32 To better disseminate the projects without such restrictions, they have created OpenHeritage 3D with Google Arts and Culture, a website dedicated to sharing some of their datasets “for education, research and other non-commercial uses”.33

These partnerships give these organizations greater oversight than their crowdsourced counterparts, but this accountability is limited; once again, it is not the source community deciding what is best for the site, but an outside agency with their own priorities.

Individual Site Projects

While the above projects focus on recording as many cultural heritage sites as they can, there are projects which focus on preserving a single place. Months before Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire in April 2019, Andrew Tallon, a medieval architectural historian, used LiDAR technology to create a detailed model of the building; following the accident, his data could be crucial in the rebuilding effort.34 Conversely, the Đình Tiền Lệ monument in Vietnam35 and the Donuimun Gate project in Seoul, Korea36 primarily seek to create digital spaces to provide new experiences to the public, rather than act solely as a reference to preserve an existing site. What they and projects like them share, though, is their goal; to understand a single place, its history, and its deeper meaning to the community around it. How this is accomplished and why, though, can vary widely depending on who is in charge of the project.

Analysis of Sites Being Preserved by Current Projects

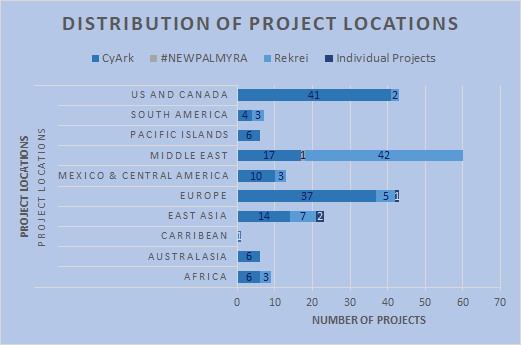

When looking at what sites are being preserved, it’s important to look at where these sites are located, to see if certain cultures’ heritage are being prioritized. This chart shows the geographic distribution of the sites declared on each of the case study projects’ websites, split into geographical regions.

In sum, it appears that most sites are either where there is easy access for the (predominantly American or European) initial creators of these projects to do their work, or where public outrage over particularly egregious site destructions has encouraged people to participate in these projects. Access is particularly key in creating a 3D object of at least artistic value, let alone one of historic or scientific value; the only way to create a good rendering of the space is through vast amounts of photographs and data points, after all, and those require time to be taken accurately. As such, projects like Rekrei and #NEWPALMYRA are limited in what they can create; because they produce models after a site has been destroyed, they are limited by what photographs they can crowdsource – if photography of the site was limited in some way prior to its destruction, then they can only produce a digital object defined by those parameters (such as being placed against a wall).37 Conversely, preservative projects tend to coordinate with the site managers to get the data they need, which means the end result is shaped by those managers’ priorities instead.38 In either case, the sites that these projects are preserving appear to have a significant bias towards Middle Eastern, European and modern American cultural heritage. While there is not an explicitly stated reason behind this bias, it still represents a significant discrepancy between these projects’ stated purpose of preserving as much of the world’s cultural heritage as possible, and the realities of what they’re actually preserving.39

How Are the End Results Distributed?

The means and circumstances under which these digital objects are created by may vary widely, but the purpose of every project is to distribute the digital objects they create in some way. While each of these sites is a vital piece of cultural heritage for at least one community, the institutional biases and other factors which lead to them being chosen in the first place may play a more significant role in how the digital representation of the site is used.

Challenges in Making Models Available to the Public

The first challenge in bringing these digital sites to the public is the restriction of the medium itself; if someone does not have access to sufficiently advanced digitally-enabled devices, they will be unable to view or interact with the site. For example, when the archives at the Sirindhorn Anthropology Center received donated anthropological materials about the Tai Lue community, they tried to consult with the source community to determine how to respectfully preserve and disseminate their cultural property. Before they could even comprehend the decision they were being asked to make, though, the SAC found that the community members they were working with needed the means to access the materials in the first place.40 Similarly, any site digitization project will be defined primarily by who has the means to access the materials they create.

To that end, the next challenge in ensuring access is to make them as widely available as possible, a goal which is often pursued by making sure the digital objects are accessible online to the public. When digitizing collections, museums have often withheld the data created from their collections and the 3D objects they created with it from the public. The hoax regarding the scans of the bust of Nefertiti at the Neues Museum, for instance, highlights how restricting public access to digital data can lead to legal and ethical issues as the public searches for ways to connect with cultural heritage.41 Though the institutions which host the data consider limited, controlled access to be in their best interest, the source communities which created the artifacts, as well as the wider public, want to interact with this heritage, and the institution’s attempts to maintain control over the digital object may adversely affect how they choose to go about doing so.42 In this respect, several of the site digitization projects have gone further in making their digital objects available to the public than those institutions; for instance, #NEWPALMYRA and Rekrei both openly and clearly license their data under a BY-NC-SA Creative Commons copyright, encouraging the public to use and interact with what they have created.43 This is not the universal stance taken by these organizations, though, as many have to deal with restrictions imposed by the site’s caretakers.

The inherent restrictions of digital restrictions play into how effective this policy of openness can be. As mentioned before, the size of the data gathered by a single project is staggering, often well outside of the resources of the average citizen to store, let alone analyze. To work around this, many of these organizations have entered into partnerships in order to disseminate their data; CyArk has partnered with Google Arts and Culture to create OpenHeritage 3D, and the Million Image Database works with partners as wide ranging as UNESCO and the Dubai Future Foundation.44 While the sites posted on Open Heritage are covered under a Creative Commons license, these licenses do not include all of the sites which CyArk has digitized, or all of the data hosted on the Million Image Database. In particular, those produced in conjunction with other agencies or other third parties tend to have restricted public access due to security or privacy concerns.45

The final challenge is making the digital objects sustainable for future generations. A few of the projects are collaborating with outside partners to gain access to resources they otherwise wouldn’t have, such as CyArk partnering with Google Arts and Culture to create online exhibits for some of their sites.46 Conversely, #NEWPALMYRA is partnering with a cryptocurrency organization to provide incentives to contributors for creating something using their data.47 However, there are few efforts which seek to give control of this data and its storage to source communities, and these outside organizations have their own priorities that could change over time. Considering how critical these sites can be to their source communities, it is another layer of stakeholders which can complicate the project’s priorities and continued existence going forward.

The Impact of Colonization on Communities’ Ability to Tell and Access Their Own Cultural Heritage

While these site digitization projects can be vital in preserving physical cultural heritage, those managing them must be mindful that they are not being run in a way that supports and sustains the impact of colonialism. Colonialism has a long legacy of disenfranchising source communities when institutions assume a position of authority to tell the story of a given object or place;48 as such, these projects must be conscious of how they are using and presenting the digital representations of these spaces. For example, even the way Western culture conceives of land ownership may run counter to how a source community conceives of their relationship to their physical cultural heritage.49 By presenting these sites as something that can be recorded, duplicated and still retain the necessary characteristics to be identified as the site itself, the projects make value judgments as to what aspects of their cultural heritage are valuable and deserve preservation.

What measures can be taken ensure that these projects are conducted in a way that respects the autonomy of these communities? The best way is to integrate their input throughout the entire process; to hold them as valuable stakeholders to consult with throughout the process.50 This can mean anything from providing training on current digitization techniques and technology, to embedding cultural protocols into the distribution process of the digital objects to ensure that the way the sites are used is in keeping with the source community’s traditions.51 Project Anqa, as mentioned before, trained Syrian professionals to give them the tools they needed to preserve their own cultural heritage in response to the ongoing civil war in their country.52 Similarly, Washington State University has partnered with Indigenous Australian communities to create Murkutu53 and with Indigenous American ones to create the Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal54 to increase their access to items of cultural heritage the university and other institutions had in their collections.

The most effective practices can vary from case to case; therefore, it’s important to make sure that source communities are consulted whenever possible. Like the sites these projects seek to preserve, time will change their needs and their priorities, and each project should be in line with the community’s most current circumstances. Several of these communities have already begun creating places where they can control their cultural heritage,55 but it is the responsibility of those who control the digital space to reach out and bring them into the space they have created.56 Since site digitization projects are usually done in collaboration with organizations from outside the source community (or even the digitization project itself) in order to gain access to more resources than they themselves can provide, there is a power imbalance built into the arrangement. To address this, the projects must actively work to provide the means for source communities to take ownership of their own heritage, and ensure that the goals of other organizations they partner with align with their own.

Ramifications of These Projects, Museum Culture and Community Rights

As these sites face increased danger as time passes, it is vital to consider the risks, possibilities and responsibilities that these projects carry. The work that they do has been and can continue to be incredibly vital to their ongoing preservation, and indeed the very existence of many cultural heritage sites around the world. However, this work does not exist in a vacuum, and there needs to be a greater awareness of the influence such projects can have on how source communities interact with their own cultural heritage.

Possibilities

By digitizing these sites, visitors and researchers alike can gain increased access to them, both for fragile sites that would be endangered by the demand of visitors,57 Ministry of Culture58 and for displaced populations looking to connect with their heritage as they are displaced from or face oppression on their homeland. This increased access also allows individuals to feel a greater connection to each others’ heritage and sympathy for the source communities which created these sites.59 For instance, digital sites can be utilized by events like the Irregular Journeys exhibition, which used 3D objects created by the #NEWPALMYRA project to foster greater understanding of the hardships the Syrian people face.60 They can also empower people to interact with these sites in unpredictable ways but which encourage greater participation with cultural heritage.61 These digital objects also give these sites’ caregivers better tools to preserve these sites in-situ, preventing their loss in the first place and protecting their relationship with their source community. Finally, they can be used to either digitally repatriate structures to their homeland,62 or be used to create replicas or supplemental materials for the museums which are repatriating related artifacts.

Risks

When determining how these digital sites will be used for the future, it’s also important to be mindful of who are making those decisions. For instance, Rekrei, which originally sought to preserve Middle Eastern cultural heritage, was founded by two European men.63 Projects like CyArk which frequently collaborate with governmental agencies to work with these sites, administration changes can mean that governments no longer consider the cultural heritage of certain source communities as important, or may use these digital heritage sites for purposes counter to the original creators’ intent. The aforementioned situation with Bears Ears National Monument64 puts this issue in sharp contrast, where even well-intentioned institutions can inadvertently end up reinforcing oppressive power structures. That situation makes clear the risks caused by not ensuring that source communities are placed in direct control of their own heritage; when that heritage is digital and can be exported wirelessly anywhere in the world, that risk is compounded significantly.

To that end, while these digital sites can be vital tools in preserving cultural heritage, they should not be considered an equal replacement for the physical site itself.65 Each site contains within it a multiplicity of history and meaning, and in choosing what parts of the site get saved and passed on to future generations, each project is passing judgement as to what part of that history is valuable. The ruins at Palmyra are being recorded; the remains of the people who had lived in those ruins for centuries who were displaced by colonial powers are not.66 In order to ensure that these projects are conducted ethically, their managers must consult directly with source communities. This ensures that they will not only record a more diverse sampling of human history, but to also ensure that what is being preserved is what the community wants to pass on as part of their heritage.

Responsibilities

In summary, throughout the process of digitizing a cultural heritage site, each step (from choosing the site to digitizing it to distributing it) should be a conscious act, cognizant of the fact that each step is a choice. Those choices inform the public what to consider valuable about that culture’s heritage, and may even come to define all future interactions with these sites. Ensuring that members of the source community are involved in all of the processes (including whether to even digitize the site in the first place) is vital to creating an ethical and sustainable digitization project. While there is no current standard consensus on how this should be done, in the absence of concrete guidance it is the responsibility of the organization that undertakes such a digitization project to reach out and include them in all stages of the process, to take steps to make sure that the ramifications of their actions are fully understood, and their actions are in keeping with the highest ethical standards possible.

Notes

- UNESCO, “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage,” in 17th General Session (Paris, 1972), Article 1, https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/. ↩

- Encycolpedia Brittanica Editors, “Palmyra,” in Encyclopedia Brittanica (Encyclopedia Brittanica, Inc., 2019), https://www.britannica.com/place/Palmyra-Syria. ↩

- William L. Ochsenwald, David Dean Commins, and Others, “Syria,” in Encyclopedia Brittanica (Encyclopedia Brittanica, Inc., 2019), https://www.britannica.com/place/Syria. ↩

- Cornelius Holtorf, Andreas Pantazatos, and Geoffrey Scarre, “Introduction,” in Cultural Heritage, Ethics and Contemporary Migrations, ed. Cornelius Holtorf, Andreas Pantazatos, and Geoffrey Scarre, 1st ed. (Routledge, 2019), 1–10. ↩

- Jonathan Seglow, “Cultural Heritage, Minorities and Self-Respect,” in Cultural Heritage, Ethics and Contemporary Migrations, ed. Cornelius Holtorf, Andreas Pantazatos, and Geoffrey Scarre, 1st ed. (Routledge, 2019), 13–26. ↩

- UNESCO, “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.” ↩

- Matthew Vincent, “About Rekrei,” Rekrei, 2019, https://rekrei.org/about. ↩

- UNESCO, “Climate Change and World Heritage,” 2007. ↩

- CyArk and US National Park Service, “Thomas Jefferson Memorial Project,” CyArk, 2018, https://www.cyark.org/projects/thomas-jefferson-memorial/overview. ↩

- “#NEWPALMYRA,” #NEWPALMYRA, 2019, https://newpalmyra.org/. ↩

- Elizabeth Snodgrass, “Ancient Maya Pyramid Destroyed in Belize,” National Geographic, 2013, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/5/130515-belize-pyramid-destroyed-archeology-maya-nohmul-world-road/. ↩

- Manuela Andreoni, “Museum Fire in Brazil Was ‘Bound to Happen,’” New York Times, September 4, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/04/world/americas/brazil-museum-fire.html?module=inline. ↩

- Jennifer Oldham, “Countless Archaeological Sites at Risk in Trump Oil and Gas Auction,” Reveal, Center for Investigative Reporting, 2018, https://www.revealnews.org/article/countless-archaeological-sites-at-risk-in-trump-oil-and-gas-auction/. ↩

- Alexis C. Madrigal, “The Images That Could Help Rebuild Notre-Dame Cathedral, and the Young, Brilliant Professor Who Made Them before He Died,” The Atlantic, April 16, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/04/laser-scans-could-help-rebuild-notre-dame-cathedral/587230/. ↩

- Brinker Ferguson, “3D Imaging a Maori Meetinghouse,” 2017, https://www.brinkerferguson.com/3d-imaging-a-maori-meetinghouse. ↩

- John Ristevski, Anthony Fassero, and John Loomis, “Historic Preservation Through Hi-Def Documentation,” CyArk, 2007, https://www.cyark.org/about/historic-preservation-through-hidef-documentation. ↩

- Alex Lubben, “Experts Are Already Arguing over How to Rebuild Notre Dame,” Vice News, 2019, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/ywygdj/experts-are-already-arguing-over-how-to-rebuild-notre-dame. ↩

- UNESCO, “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.” ↩

- Esther Addley, “Fragile Historic Buildings Open Doors to Virtual Visitors,” The Guardian, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/apr/18/fragile-historic-buildings-open-doors-to-virtual-visitors. ↩

- Friends of Cedar Mesa, “Monument History,” Bears Ears Education Center, 2019, https://bearsearsmonument.org/monument-history/. ↩

- Vincent, “About Rekrei.” ↩

- CyArk, “Thomas Jefferson Memorial, United States of America,” OpenHeritage 3D Alliance, 2019, https://doi.org/10.26301/mpkc-8q07. ↩

- Cosmo Wenman, “The Nefertiti 3D Scan Heist Is A Hoax,” Cosmo Wenman (blog), 2016, https://cosmowenman.com/2016/03/08/the-nefertiti-3d-scan-heist-is-a-hoax/. ↩

- Andy Greenberg, “A Jailed Archivist’s 3D Models Could Save Syria’s History From ISIS,” Wired, 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/10/jailed-activist-bassel-khartabil-3d-models-could-save-syrian-history-from-isis/. ↩

- Eric Steuer, “Bassel Khartabil’s Story Proves Online Activism Is Still Powerful,” Wired, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/free-bassel-essay/. ↩

- “#NEWPALMYRA.” ↩

- Vincent, “About Rekrei.” ↩

- “Irregular Journeys,” #NEWPALMYRA, n.d., https://newpalmyra.org/events/irregular-journeys-exhibition/. ↩

- Sarah Bond, “The Ethics of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage,” Forbes, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2016/09/22/does-nycs-new-3d-printed-palmyra-arch-celebrate-syria-or-just-engage-in-digital-colonialism/#677911b977db. ↩

- “Project Anqa,” accessed March 11, 2019, https://cims.carleton.ca/anqa/project.html. ↩

- CyArk & Partners, “About CyArk,” CyArk, 2018, https://www.cyark.org/about/. ↩

- CyArk & Partners, “Data Use Policy,” CyArk, 2018, https://www.cyark.org/data-use-policy. ↩

- “About OpenHeritage 3D,” OpenHeritage 3D Alliance, n.d., https://openheritage3d.org/about. ↩

- Madrigal, “The Images That Could Help Rebuild Notre-Dame Cathedral, and the Young, Brilliant Professor Who Made Them before He Died.” ↩

- Di sản Văn Hóa, “Scan of Đình Tiền Lệ Monument,” VR3D, accessed March 11, 2019, https://vr3d.vn/trienlam/3d-digitization-of-historic-monument-cultural-heritage-3d-scanning. ↩

- “Augmented Reality Brings Korean Heritage Site Back to Life,” Museum Next, 2019, https://www.museumnext.com/article/augmented-reality-brings-korean-heritage-sit-back-to-life/. ↩

- Matthew Vincent, “Rekrei Gallery,” Rekrei, 2019, https://rekrei.org/gallery. ↩

- Addley, “Fragile Historic Buildings Open Doors to Virtual Visitors.” ↩

- Partners, “About CyArk.” ↩

- Thanwadee Sookprasert and Sittisak Rungcharoensuksri, “Ethics, Access, and Rights In Anthropological Archive Management: A Case Study From Thailand,” International Journal of Humanities & Arts Computing: A Journal of Digital Humanities 7, no. March Supplement (2013): 100–110, https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2013.0063. ↩

- Wenman, “The Nefertiti 3D Scan Heist Is A Hoax.” ↩

- Michael Weinberg, “The Nefertiti Bust Meets the 21st Century: When a German Museum Lost Its Fight over 3D-Printing Files of the 3,000-Year-Old Artwork, It Made a Strange Decision.,” Slate, 2019, https://slate.com/technology/2019/11/nefertiti-bust-neues-museum-3d-printing.html. ↩

- Creative Commons, “Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International,” Creative Commons, accessed April 11, 2019, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode. ↩

- “Partners,” The Million Image Database, 2019, https://www.millionimage.org.uk/partners/. ↩

- Partners, “Data Use Policy.” ↩

- CyArk and National Parks Service, “Thomas Jefferson Memorial Project.” ↩

- Hanna Watkin, “#NewPalmyra Launches #Palmyraverse Online Space with Monthly Prompts to Create,” All3DP, 2018, https://all3dp.com/4/newpalmyra-launches-palmyraverse-online-space-monthly-prompts-create/. ↩

- Puawai Cairns, “‘Museums Are Dangerous Places’ – Challenging History,” Te Papa, Museum of New Zealand, 2018, https://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2018/10/19/museums-are-dangerous-places-challenging-history/. ↩

- Sookprasert and Rungcharoensuksri, “Ethics, Access, and Rights In Anthropological Archive Management: A Case Study From Thailand.” ↩

- Sookprasert and Rungcharoensuksri. ↩

- “Murkutu’s Mission,” Murkutu CMS, accessed April 11, 2019, https://mukurtu.org/learn/. ↩

- “Project Anqa.” ↩

- “About Murkutu,” Murkutu CMS, accessed April 11, 2019, https://mukurtu.org/about/. ↩

- “About Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal,” Murkutu CMS, n.d., https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu/about. ↩

- “About Murkutu”; “About Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal.” ↩

- Sookprasert and Rungcharoensuksri, “Ethics, Access, and Rights In Anthropological Archive Management: A Case Study From Thailand.” ↩

- Addley, “Fragile Historic Buildings Open Doors to Virtual Visitors.” ↩

- Ministry of Culture, “Lascaux,” 2019, http://archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en/visit-cave. ↩

- Holtorf, Pantazatos, and Scarre, “Introduction.” ↩

- “Irregular Journeys.” ↩

- Cosmo Wenman, “3D Scanning and Museum Access,” Medium, 2015, https://medium.com/@CosmoWenman/3d-scanning-and-museum-access-9bfbad410d46. ↩

- Brinker Ferguson, “Digital Repatriation Project,” 2017, https://www.brinkerferguson.com/digital-repatriation-project. ↩

- Vincent, “About Rekrei.” ↩

- Juliet Eilperin and Darryl Fears, “Trump Says He Will Shrink Bears Ears National Monument, a Sacred Tribal Site in Utah,” Washington Post, October 27, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2017/10/27/trump-says-he-will-shrink-bears-ears-national-monument-a-sacred-tribal-site-in-utah/. ↩

- Bernice Murphy, “Resolution No . 3 : Informing Museums on Intellectual Property Issues,” ICOM News 4, no. 3 (2007): 2007. ↩

- Ella Mudie, “Palmyra and the Radical Other: On the Politics of Monument Destruciton in Syria,” Otherness: Essays and Studies 6, no. 2 (2018): 139–60, http://www.otherness.dk/fileadmin/www.othernessandthearts.org/Publications/Journal_Otherness/Otherness_Essays_and_Studies6/2-_EllaMudie-_Palmyra_and_the_Radical_Other.pdf. ↩