IV. Selfies Worth Saving? Social Media Collecting in Museums

- Caitlin Hepner

There is no doubt that in 2019 social media is an inexorable part of life. As of this paper’s publication, some 50 billion images have been uploaded to Instagram,1 6,000 tweets on Twitter are generated every second,2 and 2.7 billion active users hold accounts with Facebook and its combined affiliates.3 From food photos, to expertly filtered selfies, and long winded video rants, each digital snapshot is embedded with information about its poster. What kinds of opportunities do such vast troves of data pose for today’s cultural institutions? One intriguing possibility comes in the form of social media collecting: a term which, for the purpose of my research, refers to a series of recent initiatives by museums to gather, document, and study content posted to a variety of social media platforms, including photos, text, and metadata.

In this paper I will situate the phenomenon of social media collecting within broader conversations taking place in the field of museums concerning curatorial authority, audience participation, and the effects of social media. I will then explore a variety of case studies that showcase how various institutions have developed tools and processes to collect content from social media, and how their conclusions could prove beneficial to the field. I will discuss two types of social media collecting initiatives: social media as an archiving tool and social media as a source for visual content analysis. Despite differences in the motivation behind these case studies, specific techniques used, and the types of information generated, collecting through social media shows how museums can move beyond traditional authority structures. It has the potential to allow museums to better preserve and understand what is meaningful to their communities while simultaneously involving audiences in the creation of, and giving them a greater stake in, museum collections.

Changing Technology, Changing Attitudes

The conversation about museums and authority began as early as 1971, when Duncan F. Cameron argued that museums should shift from functioning as a “temple” which enshrines objects deemed important by academics and the elite, to functioning as a “forum” where matters of public importance are interpreted and discussion and debate is encouraged among visitors.4

Over the course of the next fifty years scholars continued to validate and expound upon this idea, yet as of the early 2010s many museums still had not embraced the shift from “temple to forum” in practice.5 Around this time, the conversation about museum-audience relationships also took on a new dimension. As the Internet and social media had developed and expanded in influence, museum scholars began to take stock of how these technologies were shaping the museum field and contemplate how they could be harnessed in the future. They explored how the Internet had altered traditional authority structures by changing the way museums were relating to their audiences through exchange of information. In many cases these scholars advocated for more museums to embrace these changes. According to this thinking, museums are a part of the digital world whether they actively choose to be or not. Because of the sheer volume of knowledge shared online and the ubiquity of social media, audiences expect to be able to find, share, and discuss museums and their collections on the Internet. Museums must be prepared to embrace those online venues by meeting audiences where they are if they want to have control of the messaging and conversation around their collections and interpretation.6 7

Nancy Proctor, then Digital Editor of Curator: The Museum Journal, argued that due to the vast amount of knowledge circulating on the Internet the role of the curator has shifted and expanded. Once the ultimate authority on their chosen subject matter, the proliferation of voices and alternating perspectives made possible by social media has brought such a role into question. Many curators now sift through a variety of sources and discussions in order to help shape the conversation around their chosen subject matter. The rigorous training in research and critical thinking that curators undergo, when combined with detailed knowledge of their own museum’s collections, make curators uniquely qualified to consider the abundant information circulating online, and filter and validate this input. They can then make connections between all of the networks of knowledge and resources in order to provide a more holistic interpretation of their subject matter which encompasses their own expertise but also considers the perspectives of many. Proctor offers examples of this type of curatorial ethos, including online “crowdsourcing” initiatives undertaken by various museums in which online users were empowered to vote for works to be exhibited, as well as the Powerhouse Museum’s effort to crowdsource enhanced information on their collections through online tools. This was achieved by allowing users to submit their own research relating to objects whose records were incomplete in their online database . Through these efforts, curators demonstrated how knowledge from “citizen curators” could be effectively integrated into their own work. Proctor concluded that curators should be mediators of information, collaborators, and storytellers; no longer positioned at the top of a conceptual pyramid, but a node at the center of an information network. This reflects a subtle, yet important shift in the nature of museum and curatorial authority.

Rob Stein presents similar ideas, referring to curators as “content specialists” and relating them to reference librarians who are trained to support researchers and scholars by sorting through vast resources to find relevant information.8 Much like Proctor, he argues that curators must be mediators of information within a network, in which they connect scholars and audiences with “important concepts, facts, and narratives that drive the mission of the museum.”9 He believes that curators should foster a “participatory culture” in museums in which barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement are low, there is support for sharing one’s artistic creations, and what is known by the experienced is passed along to novices.10 He argues that participatory culture is on the rise thanks to social media and the ability it grants individuals to widely distribute their thoughts and ideas. Audiences not only expect to find information about museums online, but they expect to be able to participate in the creation of this knowledge through engagement with museum social media channels. Stein emphasizes that while this information may seem unimportant or frivolous at first, it has the potential to be insightful and useful to museums. Acknowledging and inviting public input helps museums to determine what is important to their audiences and fosters a relationship with their communities. Ultimately, he argues that more museums must embrace and develop new forms of participatory culture in order to meet audience expectations and give audiences a stake in their continued success.

Taken together, these scholars present a new picture of authority in museums, in which information no longer flows in one direction from the museum to the audience, but is exchanged between the parties in a mutually beneficial arrangement. Museums are able to meet their audience’s expectation and desire to participate, gain new kinds of knowledge and insight pertaining to their collections, and increase community support and buy-in. As we approach the turn of the next decade, these sentiments continue to ring true. When museums choose to gather and scrutinize content from social media, they are demonstrating this exchange of information with audiences, and validating this content as worthy of consideration and study. Thus, social media collecting by museums is an expression of evolving technologies, audience expectations, and attitudes about museum authority.

Social Media as an Archive

Some museums have embraced social media collecting as a sort of digital archive. Haidy Geismar’s research on Instagram, calling it an “unruly and instant archive,” first provided the rationale for why social media could be considered through this lens.11 This conceptualization is useful because it sheds light on how contemporary culture is created and shared as social media and the practice of communicating through images has evolved to become “a new kind of institution within our everyday lives.”12

Geismar explains that like an archive, Instagram presents images in a chronological stream, which can be gathered into sub-groups with the use of hashtags or geolocation tags. The hashtag is an important archival tool because it allows users to generate a sort of folksonomy, or a classificatory system for the content they create.13 Using hashtags, users can cluster their images around any number of specific themes and ideas such as events or commodities. This allows Instagram users to generate a shared visual culture around these topics, build communities, and engage in conversation across the platform. Thus, Instagram is a place where new visual culture is simultaneously created and recorded. Geismar concludes that Instagram is an “archive of the everyday” which provides the digital infrastructure to see “assemblages of taste.”14 By viewing Instagram as an archive, one can understand what is valuable and meaningful to people.

This argument has been applied to the museum field and expanded through an ongoing research project entitled Collecting Social Photo (CoSoPho), which was devised by a group of researchers from various Nordic institutions. Like Geismar, the researchers of CoSoPho argue that social media is where visual culture is increasingly created and captured. However, they move beyond the idea of social media as an archive in itself; they also aim to develop comprehensive procedures for museums to collect and disseminate their own collections of social media photography.15

The project website proclaims that the evolution of digital photography and social media has drastically changed how people use photos in their everyday lives. Social media photos differ from traditional photographs because they are not static, physical objects. They are instead assemblages of digital image, text, and metadata. They are not simply “scientific evidence, memories or art,” but are also “part of a dialogue, an ongoing online conversation.”16 However, the members of CoSoPho observe that museums are not currently equipped to collect and preserve these ephemeral images and their associated meanings for future generations. Despite this, they urge other museums to be proactive in the effort to collect social media content. These individuals have undertaken several projects within their own institutions to serve as case studies, such as collecting photos associated with the holiday season in Aalborg, Denmark, and documenting online representations of the city of Södertälje, Sweden, through which they hope to test various social media collecting strategies. From this research they aim to develop recommendations and procedures for collecting and disseminating social photography collections. They also hope to establish work practices around the co-creation of photography collections between museums and audiences in order to explore the potential for people to be involved in the generation and preservation of their own digital cultural heritage.

Interestingly, the members of CoSoPho have organized their projects around three themes: places, practices, and events.17 Place-based collecting is an effort to digitally document a specific town or physical community by collecting social media content associated with that place through hashtags and geolocation tags. Practice-based collecting involves tracking the social media practices of a particular individual over a period of time, encouraging them to reflect on their own habits, and interviewing them in order to gain a narrow but deep insight into these habits. Event-based collecting represents an effort to create a framework for how museums can collect social media content in real time in order to capture and document how important events and cultural movements manifest online.

For the purpose of this paper, I will expound upon an example of event-based collecting from The Nordic Museum and Stockholm County Museum in order to offer insight into some of the collection methods and conclusions that can be gained from social media archiving.18 Following the terrorist attack in Stockholm in April 2017 researchers directed audiences via social media to contribute images to two purpose-built digital collecting websites and utilized an unnamed third-party application to download metadata from images of the attack posted on Instagram.19 In their conclusions the CoSoPho researchers highlight the importance of having the digital infrastructure and workflow in place ahead of time in order to be prepared to collect spontaneously as events transpire, as well as proper outreach surrounding the event in order to achieve as much engagement as possible. They posit that the stories and data generated from this type of collecting could be useful for new forms of interpretation and visualization to demonstrate how real-world events unfold in the digital sphere.

Utilizing social media as an archive allows museums to better preserve the cultural heritage which is increasingly being created and stored online while simultaneously gaining a deeper understanding of what is meaningful to audiences. When users submit their own content to these digital archives they are actively engaging in the creation of these collections. In this way, these initiatives demonstrate how museums can foster participatory culture and share curatorial authority with their audiences.

Social Media for Visual Content Analysis

Other researchers have developed social media collecting techniques in order to study visitor engagement with objects and exhibition spaces through visual content analysis. Visual content analysis is the process of examining and analyzing a group of images for patterns or embedded codes in order to draw greater conclusions about their meaning.20

Kylie Budge used visual content analysis to interrogate the role of social media in audience experience in her article, “Objects in Focus: Museum Visitors and Instagram.”21 She situated her study within the previously summarized conversation relating to museum authority, articulating that museums now encourage social media users to initiate the sharing and creation of cultural knowledge, which represents a shift away from the traditional one-way flow of information from museum to audience, and towards an exchange of information between the two. This sort of study is useful, she argues, because of its potential to illuminate “meaning-making” by museum audiences. This is a term she uses to describe, “how people interpret their environment and understand their lives through what they know, believe, and experience.”22 Collecting and analyzing visitor generated social media content allows museums to know what is meaningful to their audiences, which could then potentially be used to inform curatorial and exhibition practices and foster deeper engagement with future visitors.

In her study, Budge applied visual content analysis to Instagram posts associated with a temporary exhibition, titled Recollect: Shoes, at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney, Australia. She focused on Instagram because of the visual nature and widespread popularity of the platform. Using a program called “Gramfeed” 23 she tracked posts containing the hashtag #recollectshoes and relevant posts associated with the museum’s geolocation tag. She then saved the posts to a Microsoft Word document where they could be referenced during different stages of analysis. Additionally, she printed each post in color and pinned it to a wall so they could all be seen and considered at once, which allowed visual patterns to be more easily identified.

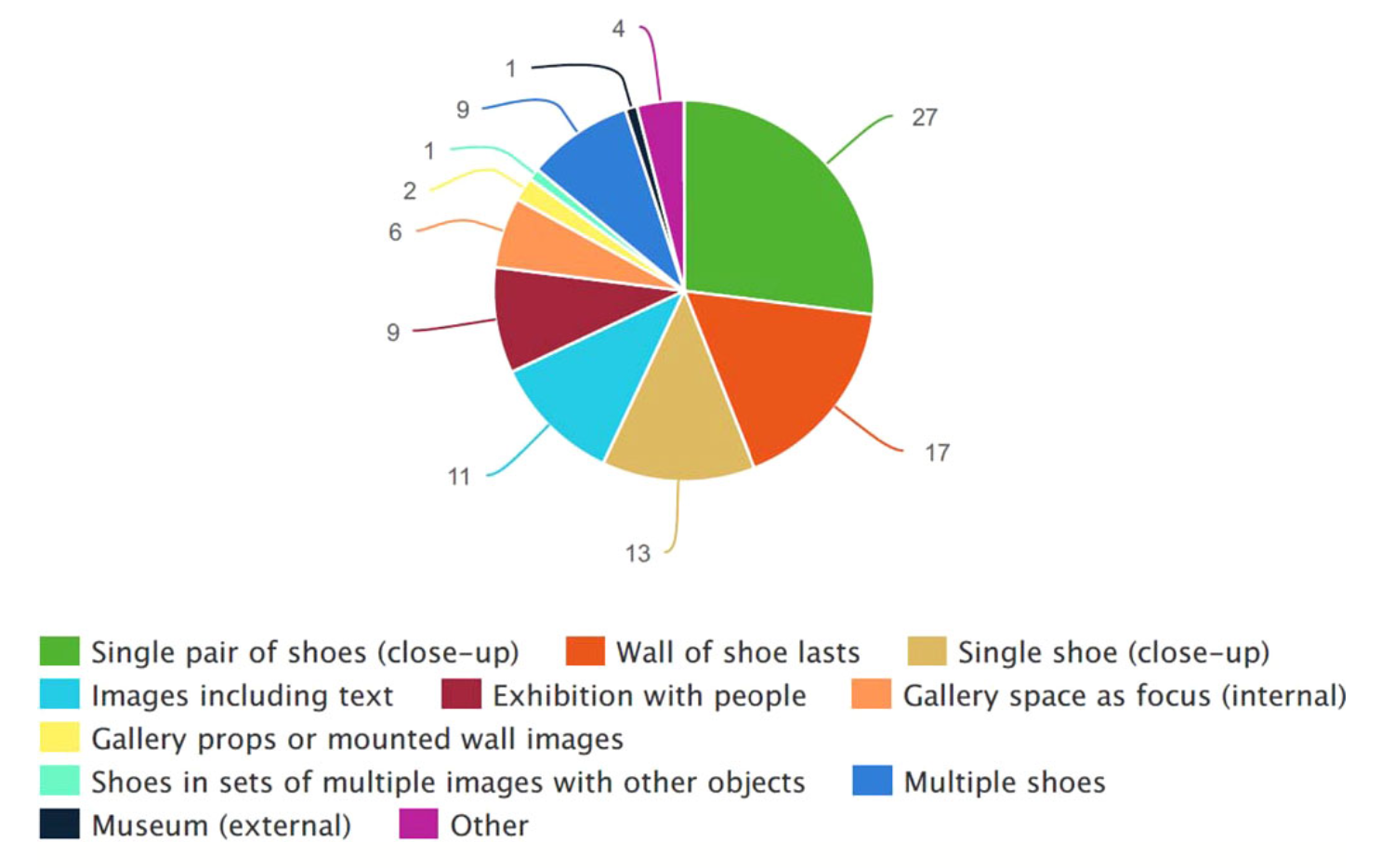

Through these methods Budge identified four main types of user generated images, and from them drew a number of potentially useful preliminary conclusions. 49% of images featured shoes in some way, including single shoes (27%), pairs of shoes (13%), and multiple shoes (9%). These photos often focused on the decorative details, form, and materials of the shoes. The second largest category, at 17%, included images of a main feature of the exhibition: a wall-mounted collection of shoe molds or “lasts.” Within the data set the shoe lasts were always represented as a group, never individually. Taken together, this demonstrated a focus on the material and aesthetic qualities of exhibit objects, such as the patterns, colors, and textures of the shoes, as well as the aesthetics of many similar objects presented as a collection through repetition, such as the wall of shoe lasts. The third largest group, at 11%, contained images of large banners associated with the exhibit. These banners included shoe-related quotes from well-known sources such as “The right shoe can make everything different,” by Jimmy Choo. Some of the quotes were shared more often than others, perhaps indicating which quotes audiences found most relatable or meaningful. The final significant category, at 9%, consisted of images that included people. Yet even in these photos, objects and elements from the exhibition remained as the focal point, and none of them could be considered “selfies” in which a person is the main subject. This fact, argues Budge, coupled with the overall infrequency of photos that even contained people, provides evidence to counter the concerns of some in the museum field who express worry that visitors taking in-gallery photos are primarily interested in documenting themselves rather than engaging with exhibition content.24

In summary, the results of Budge’s visual content analysis indicate that visitors to the exhibition were primarily interested in the objects on display rather than people. She also posits that the parts of the exhibit that were aesthetically appealing and those that had more personal meaning to the visitor were more likely to be represented on Instagram. While some of these conclusions may seem obvious to the seasoned museum professional, what is useful about this strategy is its ability to either bolster anecdotal observations with data, or in some cases, unsettle widely held ideas about how museum visitors are using social media to interact with objects and exhibition spaces.

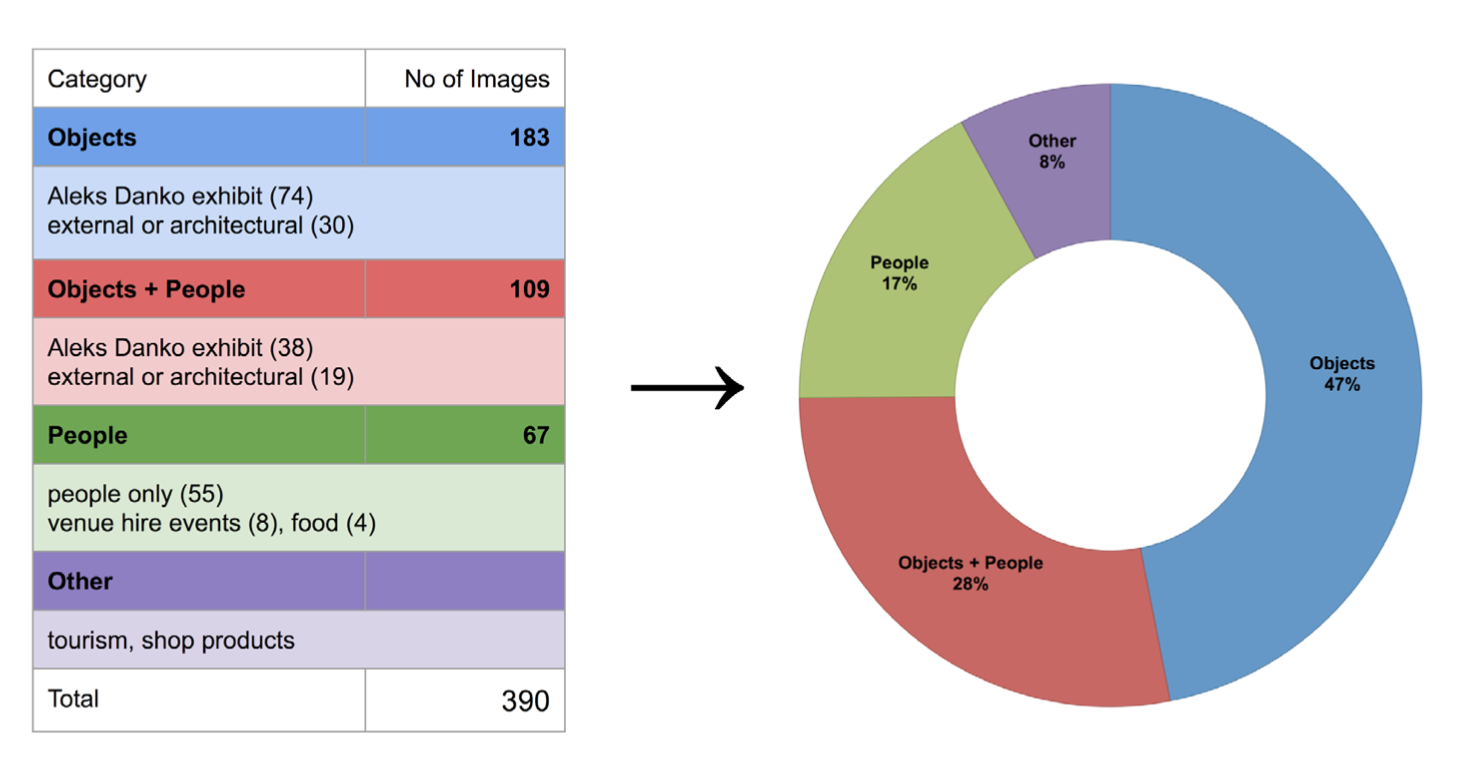

In a second case study, Kylie Budge and co-author Alli Burness expanded their scope to a museum-wide approach in their article entitled, “Museum Objects and Instagram: Agency and Communication in Digital Engagement.”25 For this project they collected and analyzed every photo with a geolocation tag associated with the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Sydney, Australia, over a period of seven days. Similar to Budge’s solo project, their guiding research question was “How are visitors who take photos and post them to Instagram engaging with museum objects?” For the purpose of their research they designed a semi-automated data collection technique. First, they set up a dedicated Instagram account for the project. Then, using a web service called “If This Then That” 26 they set a series of conditions to allow Instagram images and metadata to be exported to a variety of savable formats. The exportation was triggered when researchers favorited images from the Instagram account, thus allowing them to select and collect images associated with the MCA geolocation tag for analysis. Once again images were printed and posted on a wall together, where they could be examined for visual patterns and themes.

The researchers identified three major subgroups within the data. 47% percent of photos depicted museum objects, 28% depicted museum objects and people, and 17% depicted people. A handful of preliminary conclusions became readily apparent. Three quarters of the photos gathered contained a museum object in some capacity, suggesting once again that museum objects were of primary importance to visitors rather than people. It also quickly became apparent which objects were posted most often, which could lend insight into which objects were most popular with audiences, or at least made the greatest impression upon them.

After more consideration and study two themes emerged across the three categories. The first theme the researchers identified was “agency and authority.”27 When visitors take photos of themselves alongside objects and express their own thoughts and opinions about the objects in their captions, they are inserting themselves into the museum exhibition both physically and figuratively. In their captions they draw connections between themselves, the objects they are viewing, and their own thoughts and feelings. In this way, the user has the “agency” to take interpretation of the exhibition materials into their own hands, and the platform gives them the “authority” to do so. These types of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral investments show that audiences are using social media to engage deeply with museum objects.

The second theme that emerged was the idea of communicating a shared experience through photography. Posts in this vein are like windows into the visitor’s experience of the museum and also lend insight into how they conceptualize themselves and signal belonging to their own communities. For example, one visitor chose to post a collage of many snapshots from their visit. This is a method of sharing many separate impressions in order to communicate a summary of their time at the museum. The caption included the phrase “Imma do me” suggesting that they felt the works they choose to share were in some way emblematic of who they are. Additionally, the inclusion of a hashtag “#somanyhipsterartgrads” suggests a, “humorous identification or sense of affiliation with such an imagined community also in attendance at the MCA.” 28 Through this post, the visitor shared their personal art preferences and signaled (ironically) their belonging to a group of so called “hipster art grads” to their own social media audience. Through this form of visual communication visitors can share their experiences involving museum objects and connect them to themselves and their online communities.

Returning to their research question, Budge and Burness found that museum visitors use social media to engage with objects and exhibition spaces as a means of expressing their own agency and authority over the concepts presented to them onsite and as a means of communicating and connecting with others. They conclude that the insights generated through visual content analysis could potentially inform future curatorial and exhibition choices and illuminate methods for museums to more deeply and meaningfully engage their audiences.

These findings explicitly link to ideas presented by Proctor and Stein, who argued that social media has created a proliferation of voices around museum collections, and that users now expect to actively participate in the sharing and creation of knowledge around museum objects and exhibitions. Visual content analysis therefore is a means of gathering these perspectives, studying them, and making curatorial decisions based on them. When museum professionals treat content created and shared by visitors as a valuable source for information, they demonstrate a willingness to share curatorial authorship with the public, and foster participatory culture within their institutions.

Conclusion

Social media is now where culture itself is created, expressed, and captured. It is often the first place people go when they want to learn something new or share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It is vital for museums to develop the tools and processes for collecting, studying, and sharing the relevant elements of social media in order to connect what happens there to their own collections. In this way museums can meet evolving expectations for user participation and foster deeper connections with audiences.

However, this area of research is still incredibly young. The members of CoSoPho, Budge, and Burness have all acknowledged in their work that their findings are preliminary, that they should not be taken at face value, and that much more testing and follow-up is needed in order to fully realize the potential benefits that social media archiving and visual content analysis could contribute to the museum field.

Techniques and procedures for collecting and archiving social media content are far from standardized. Researchers will need to continue to experiment and test methods and procedures for efficiently gathering, storing, and possibly distributing this data. They must also contend with ever-evolving audience expectations and proprietary social media platforms.

More study in general is needed in order to gain a representative understanding of how social media collecting as a tool can be implemented within a diverse set of institutions of varying sizes, locations, and types of collections. Additionally, because the aforementioned case studies are so recent, little has been written about how institutions have implemented the information gained through this research. Future follow-up studies could shed light on the challenges and successes stemming from these early social media collecting initiatives.

Finally, it is of utmost importance that researchers in this field commit to having conversations and developing guidelines concerning the ethics of the practice of social media collecting. Is it appropriate for museums to circulate a call for photos and testimony in the immediate wake of a traumatic event such as a terrorist attack? Is it acceptable to archive, analyze, or publish public social media content without the express permission of the original creators? How would ethical considerations vary between a large-scale social media archiving project, a user-submitted archiving project, or the collection of content for internal study purposes? Many of these questions have already been raised in the research summarized in this paper. However, they will need continued debate in order for professionals to reach an adequate conclusion as the practice of social media collecting becomes more accepted and uniform.

My hope is that museum professionals will continue to experiment with techniques to collect and analyze social media, to develop appropriate technical and ethical guidelines, and to implement positive change at their institutions based on their findings.

Notes

- Omnicore Agency, Instagram by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics, and Fun Facts, n.d. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/ (accessed Nov. 3, 2019). ↩

- Internet Live stats, Twitter Usage Statistics, n.d. https://www.internetlivestats.com/twitter-statistics/ (accessed Nov. 3, 2019). ↩

- Statista, Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 2nd quarter 2019 (in millions), n.d. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ (accessed Nov. 3, 2019). ↩

- Duncan F. Cameron, “Museum, a Temple or the Forum.” Curator: The Museum Journal. 14, no. 1 (1971): 11-24. ↩

- Lori Byrd Phillips, “The Temple and the Bazaar: Wikipedia as a Platform for Open Authority in Museums,” Curator: The Museum Journal 52, no. 2 (2013): 219-235. ↩

- Nancy Proctor, “Digital: Museum as Platform, Curator as Champion, in the Age of Social Media,” Curator: The Museums Journal 53, no. 1 (2010): 35-43. ↩

- Robert Stein, “Chiming in on Museums and Participatory Culture,” Curator: The Museum Journal 55, no. 2 (2012): 215-226. ↩

- Robert Stein, “Chiming in on Museums and Participatory Culture,” 218. ↩

- Robert Stein, “Chiming in on Museums and Participatory Culture,” 218. ↩

- Henry Jenkins, as quoted in Robert Stein, “Chiming in on Museums and Participatory Culture,” 216. ↩

- Haidy Geismar, “Instant Archives?” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography ed. Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell. (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 331. ↩

- Haidy Geismar, Instant Archives?, 342. ↩

- Haidy Geismar, Instant Archives?, 336. ↩

- Haidy Geismar, Instant Archives,_ 341. ↩

- #Collectingsocialphoto, About the Project, n.d. http://collectingsocialphoto.nordiskamuseet.se/about/ (accessed Nov. 03, 2019). ↩

- #Collectingsocialphoto, About the Project, n.d. http://collectingsocialphoto.nordiskamuseet.se/about/ (accessed Nov. 03, 2019). ↩

- #Collectingsocialphoto, Case Studies, n.d. http://collectingsocialphoto.nordiskamuseet.se/about/ (accessed Nov. 03, 2019). ↩

- Kajsa Hartig, Bente Jensen, Anni Wallenius, and Elisabeth Boogh, “Collecting the ephemeral social media photograph for the future: Why museums and archives need to embrace new work practices for photography collections.” MW18: MW 2018. Published January 15, 2018. ↩

- Kajsa Hartig et al “Collecting the ephemeral social media photograph for the future: Why museums and archives need to embrace new work practices for photography collections. ↩

- Gillian Rose, as quoted in Kylie Budge, “Objects in Focus: Museum Visitors and Instagram,” Curator the Museum Journal. 60, no. 1 (2017): 71. ↩

- Kylie Budge, “Objects in Focus: Museum Visitors and Instagram,” 67-85. ↩

- Branford et al, as quoted in Kylie Budge, Objects in Focus: Museum Visitors and Instagram,” 67. ↩

- Gramfeed is now Picodash n.d. http://www.gramfeed.com/ (accessed Nov. 18, 2019). ↩

- Kylie Budge, “Objects in Focus: Museum Visitors and Instagram,” 79. ↩

- Kylie Budge and Alli Burness, “Museum Objects and Instagram: Agency and Communication in Digital Engagement.” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies. vol. 32, no. 2 (2018): 137-150. ↩

- “IFTTT: Every Thing Works Better Together.” n.d. https://ifttt.com/ (accessed Nov. 18, 2019). ↩

- Kylie Budge and Alli Burness, “Museum Objects and Instagram: Agency and Communication in Digital Engagement,” 144. ↩

- Kylie Budge and Alli Burness, “Museum Objects and Instagram: Agency and Communication in Digital Engagement,” 145. ↩