XII. Examining Biases in GLAM Data and Metadata

- Cristin Guinan-Wiley

I owe an incredible debt of gratitude to Patrick Bond for assisting me with the technical aspects of this paper. Additionally, I believe it is important to situate my own perspective and background as a cis-het white woman from a fair amount of privilege as it is only by acknowledging our own biases that we can begin to look beyond them.

Within the world of Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums there are seemingly endless individual objects and each of these objects need to be classified, categorized, and tagged. Constructing these classifications, categories, and tags creates order out of what would otherwise be chaos, gives objects physical and temporal context, and allows for relationships between objects to be seen. However, creating the standards that govern these classifications, categories, and tags is highly subjective and can reflect the biases of the people or culture that is creating them.1 Many GLAM institutions have made their collections and the data associated with their collections open access so it is possible for external personnel to evaluate what biases may exist within the metadata themselves and also what biases may exist in individual institutions and across the GLAM community by looking at data across institutions. The purpose of this paper is to examine how bias can be revealed in GLAM data and metadata.

The inspiration for this paper came from a distillation of many sources with the following four forming the primary impetus; First being the writings of Michell Caswell2 and her presentation at the 2019 iPRES3conference in Amsterdam, in which she discusses using feminist standpoint epistemologies4 to evaluate archival appraisal along with the importance of acknowledging internal bias. The second being the work done to decolonize collections data for indigenous collections.5 The third source is the work of Fiona Cameron, specifically her paper with Helena Robinson on “Digital Knowledgescapes”.6 The final piece solidifying this subject came from one of the proposed topics listed for the upcoming 2020 Gender and Sexuality in Information Studies Colloquium7: “How do search algorithms, metadata standards, and user interfaces challenge or reinforce white supremacy, heteronormative patriarchy, and ableism?” To fully answer that question would be beyond the scope of this format; thus, it was decided to focus on language usage in metadata to breach the surface of the topic.

What is Metadata?

Prior to exploring the impact of metadata, the first step is to lay out a general definition for the subject, and then identify the types of metadata that are typically used in GLAM institutions. The concept of Metadata was not created with the advent of the digital age. The purest definition of the word is “data about data” and at essence, is used to ‘tag’ one piece of information (or object, or person) with identifying information. The usage of metadata dates to the library of Alexandria (ca. 3rd century BCE- 48 CE), where the librarians would physically place tags on the scrolls with author, title, and subject.8 That format developed into the card catalogue. Names, dates, and locations written on the back of photo prints constitute metadata. With the rise of computers, standards of digital metadata began to take shape.9 In the age of the internet, metadata are produced by most every action on the internet automatically. For instance, every email sent contains a variety of data that are not seen in standard user interfaces and are added at different points along its journey to the recipient.10 Therefore, it can be said that digital metadata can be basically broken down into two types-those which are algorithmically (human by proxy) created, and those which are created by a user (human).

Museum metadata are almost entirely created by human activity, though there are current projects that are working towards an automated process.11 There are also an array of metadata standards and of controlled vocabularies used in GLAM institutions some of which are specialized for certain collections.12 However, within museums, metadata can be broadly divided up into five basic groups:

| Type | Function |

|---|---|

| Administrative | Acquisition number, location, rights tracking, legal issues with access. |

| Descriptive | Author/creator, dates, materials, relationships with other collection objects, curatorial notes and essays. |

| Preservation | Physical condition of the object and if it has changed over time, any actions that have been performed to extend the life of the object both in its physical and digital form (eg. data migration) |

| Technical | Digitization information (formats, compression, scaling), required hardware and software, digital security measures |

| Use | Exhibition data, user use of the object, rights and reproduction information, reuse of the object and versioning data. |

Table 1. Adapted from “Introduction to Metadata” Edited by Murtha Baca13

How metadata can contain and show bias

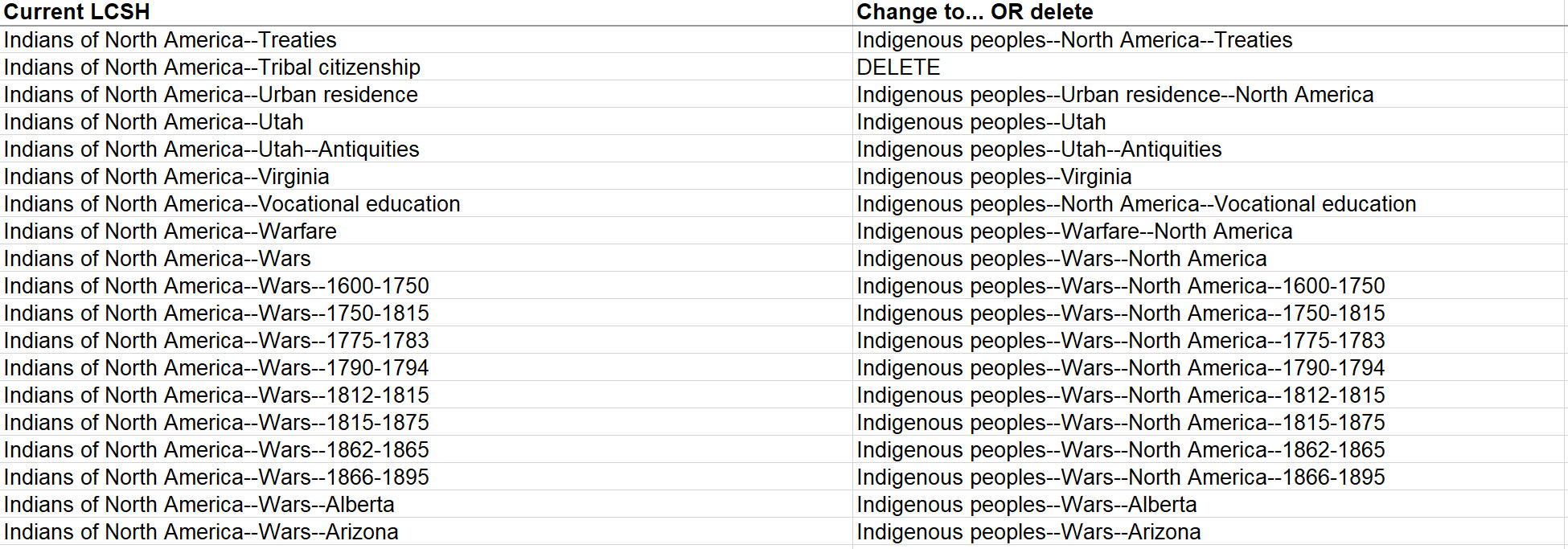

The most easily seen way that metadata can perpetuate bias is through a use of language (controlled vocabulary) that is biased, especially in subject headings and tagging. One example of this is a project at the University of Alberta whose purpose is “ To investigate, define and propose a plan of action for how the University of Alberta Libraries can more accurately, appropriately, and respectfully represent Indigenous peoples and contexts through our descriptive metadata practices.”14 A project that they are using to look at their own metadata is the Manitoba Archival Information Network’s (MAIN) project to change Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) in cases where the current subject headings (tags) are insensitive to the Indigenous Peoples in Manitoba and add additional subject headings that are more specific and reflective of the Indigenous culture.15 The vast majority of the changes consisted of taking every instance of ‘Indian’ and replacing it with “Indigenous”:

The subject heading issues surrounding Indigenous collections are fairly blatant however, there are other situations where the issue is not as cut and dry as changing the language but instead about how to give the desired weight to different objects that have the same tag. One such circumstance is another project out of the University of Manitoba, The Digital Archives and Marginalized Communities Project (DAMC)16 which is a project that is developing three different but interrelated archives. One of these archives in development is the Sex Work Database (SWD). In their paper “Tagging for activist ends and strategic ephemerality: creating the Sex Work Database as an activist digital archive” Shawna Ferris and Danielle Allard discuss the community-produced controlled vocabulary and how they “are developing a tagging system that is designed to draw records into conversation with one another in ways that privilege sex worker activist messaging”.17 The example they discuss is for the tag “prostitute” which when searched or clicked on would bring results not only from the mainstream media, which tends to dehumanize sex workers18, but also give equal or higher weight to works from the point of view of sex workers.19

What all of these projects call into focus is the need for community involvement when creating controlled vocabularies especially when creating a new collection or housing a collection that was obtained unethically in the past. I believe that especially now that collections data are becoming more open access with increased public interaction with those data, GLAM institutions must shed the concept of being the ‘ultimate authority’ and understand that objects are polysemic.20

Examination of Digital GLAM data

Metadata can also show bias at an individual institutional or even at the broader GLAM community level when looked at in the aggregate and as part of my research for this paper I wanted to do a comparative study of descriptive data across several museums to see if any bias was detectable. However, due to time constraints and the steep learning curve a project such as this would require it was not feasible. Instead, I performed a study of the Tate object file to look for the trends in the acquisition of art by women. Prior to getting to that result I am going to introduce and describe a few of the other data sets I looked at and their file formats.

There are two excellent sources I am aware of for locating open access data from museums; one is the “Survey of GLAM open access policy” Google spreadsheet by Douglas McCarthy and Dr. Andrea Wallace CC BY 4.0, 2018-present21 and another is the Museum APIs page on the Museums and the machine-processable world wiki maintained by Mia Ridge.22 The data I looked at primarily consisted of two formats; CSV (comma separated values) and JSON (JAVA Script Object Notation). While CSV files can be used with several applications, they are primarily used with spreadsheets. When imported into an application like Microsoft Excel, they typically result in simple spreadsheets. In the case of GLAM data, these files are normally bounded to one set of subjects such as artists, artworks, authors, documents, etc…The columns are the metadata shared by all the objects.

An example would be the SherlockNet data set developed by Luda Zhao, Brian Do, and Karen Wang for their project for the British Library Labs Competition: “Using Convolutional Neural Networks to Explore Over 400 Years of Book Illustrations”.23 In the most simple of terms they trained a machine in the tags they wanted it to use and then had it tag and caption the 1 million images in the British Library 1M Collection which consists of scans of book illustrations from 1500 to 1900. The CSV file (sherlocknet_tags_verbose) that came out of this project has the following columns of data: image_idx; flickr_id; tag; size; scannnumber; imageorder; title; author; vol; pubplace; sysnum; date; filename. An example of one of the image’s data set in an inverted format for ease of reading is:

| Field | Data |

|---|---|

| image_idx | 28 |

| flickr_id | 11219063183 |

| tag | people |

| size | m |

| scannumber | 46 |

| imageorder | 1 |

| title | Songes and Sonettes |

| author | HOWARD, Henry Earl of Surrey |

| vol | 0 |

| sysnum | 1746417 |

| date | 1567 |

| filename | 001746417_0_0000461 |

Table 2. Example of the data from the SherlockNet CSV file

For this format to be efficient the metadata tends to be limited to attributes that all the objects in the data file share. Metadata elements which only a belong to a subset of the objects under consideration result in lots of empty cells and cumbersome spreadsheets. Consequently, the simple structure can be limiting. However, spreadsheets tend to be well understood and for most non-technical people, these data are easy to work with. In the case of this object all of the tags generated by sherlocknet can be seen on its flicker page.24

JSON files have a richer and more complex structure. The objects are described in JAVA Script which allows each object to have attributes (metadata) not shared by similar objects while avoiding the inefficiencies of the spreadsheet’s many blank cells. However, while this format is human readable, the entries tend to be very lengthy and are only easily interpreted through the use of a customized application. For example, consider the spreadsheet style data (CSV) for a given artwork. For this example, I am using the Tate object file as it was the one I spent the most time with.

| Field | Data |

|---|---|

| id | 1037 |

| accession_number | A00003 |

| artist | Blake, Robert |

| artistRole | artist |

| artistId | 38 |

| title | The Preaching of Warning. Verso: An Old Man Enthroned Between Two Groups of Figures, by ?William Blake |

| dateText | ?c.1785 |

| medium | Graphite on paper. Verso: graphite on paper |

| creditLine | Presented by Mrs John Richmond 1922 |

| year | 1785 |

| acquisitionYear | 1922 |

| dimensions | support: 343 x 467 mm |

| width | 343 |

| height | 467 |

| depth | |

| units | mm |

| inscription | |

| thumbnailCopyright | |

| thumbnailUrl | http://www.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/A/A00/A00003_8.jpg |

| url | http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/blake-the-preaching-of-warning-verso-an-old-man-enthroned-between-two-groups-of-figures-by-a00003 |

Table 3. Example of the data from the Tate CSV object file

Now consider the corresponding JSON entry:

{

"acno": "A00003",

"acquisitionYear": 1922,

"all_artists": "Robert Blake",

"catalogueGroup": {},

"classification": "on paper, unique",

"contributorCount": 1,

"contributors": [

{

"birthYear": 1762,

"date": "1762\u20131787",

"displayOrder": 1,

"fc": "Robert Blake",

"gender": "Male",

"id": 38,

"mda": "Blake, Robert",

"role": "artist",

"startLetter": "B"

}

],

"creditLine": "Presented by Mrs John Richmond 1922",

"dateRange": {

"endYear": 1785,

"startYear": 1785,

"text": "?c.1785"

},

"dateText": "?c.1785",

"depth": "",

"dimensions": "support: 343 x 467 mm",

"foreignTitle": null,

"groupTitle": null,

"height": "467",

"id": 1037,

"inscription": null,

"medium": "Graphite on paper. Verso: graphite on paper",

"movementCount": 0,

"subjectCount": 5,

"subjects": {

"children": [

{

"children": [

{

"children": [

{

"id": 1050,

"name": "arm/arms raised"

},

{

"id": 270,

"name": "standing"

}

],

"id": 92,

"name": "actions: postures and motions"

},

{

"children": [

{

"id": 799,

"name": "group"

}

],

"id": 97,

"name": "groups"

},

{

"children": [

{

"id": 195,

"name": "man"

}

],

"id": 95,

"name": "adults"

}

],

"id": 91,

"name": "people"

},

{

"children": [

{

"children": [

{

"id": 12297,

"name": "preaching"

}

],

"id": 120,

"name": "religious"

}

],

"id": 116,

"name": "work and occupations"

}

],

"id": 1,

"name": "subject"

},

"thumbnailCopyright": null,

"thumbnailUrl": "http://www.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/A/A00/A00003_8.jpg",

"title": "The Preaching of Warning. Verso: An Old Man Enthroned between Two Groups of Figures, by ?William Blake",

"title": "The Preaching of Warning. Verso: An Old Man Enthroned Between Two Groups of Figures, by ?William Blake",

"units": "mm",

"url": "http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/blake-the-preaching-of-warning-verso-an-old-man-enthroned-between-two-groups-of-figures-by-a00003",

"width": "343"

}

As you can see, this is far more difficult to read and not as easily understood. However, while it contains the same metadata elements that appear in the columns of the CSV spreadsheets, it also contains additional “descriptive” elements. In this case there are also fields that describe actions associated with the artwork with values such as: “actions: postures and motions”; “hand/hands raised”; “standing”; “looking / watching”.

Maintenance of JSON files can be incredibly time consuming. For example, the Tate JSON files had 64,819 changed files with 253,856 additions and 54,402 deletions.

Research Project based in the Tate’s data

As I stated above, rather than do a comparative study of metadata over several institutions I made an examination of the acquisition trends at the Tate in terms of Gender. This required the combining of the two CSV data sets available from the Tate on GitHub.25 The object file has the columns as described in Table 3 and thus does not have a column for Artist gender so I inserted a column for gender and used the Tate’s Artist file to assign gender to the artists in the object file. I did not attempt to confirm any of the data nor did I attempt to clean any of it, thus any artist that did not have a gender assigned in the Tate’s file did not have one assigned in the object file. I did find it interesting to note that while all the artists in the object file were present in the artist file a very few of the artists listed in the artist file were not in the object file. All this does is remind one of how messy data can be. It should also be noted that none of the files in the Tate GitHub have been updated since October of 2014.

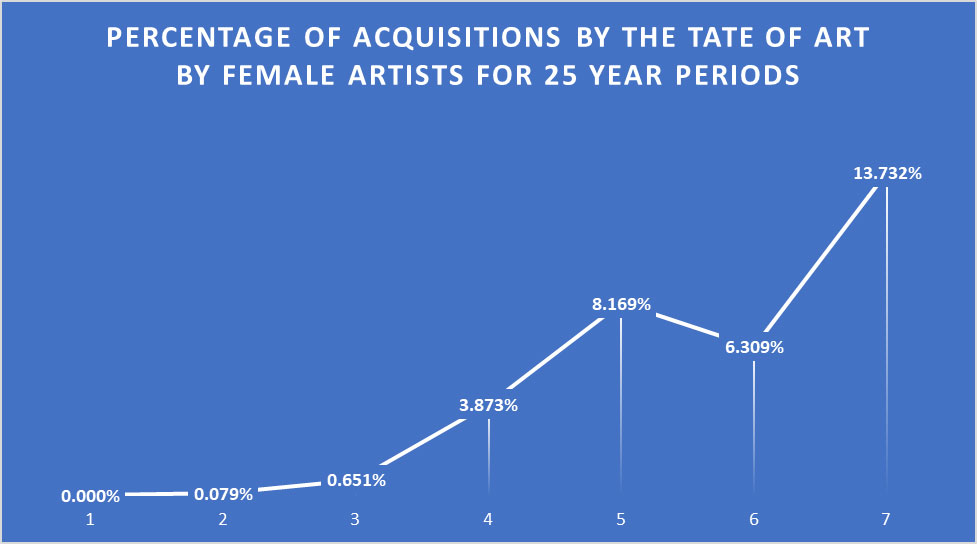

Some basic statistical notes on the Tate collection according to this file are; the total number of artworks listed is 69,201; that only 1.1% of the collection does not have an artist with a gender assigned (very few of these were individuals and most were a variation on “British School”); 95% of the collection is by male artists; and only 3.9% of the collection is by women artists. However, I am not the first person to examine this object file and it was noted by Florian Kräutli in his Doctoral thesis “Exploring Digital Collections Through Timeline Visualizations”26 that art by Joseph Mallord William Turner constitutes 57% (56.9%) of the works at the Tate.27 Removing his data leaves the collection at 88.5% male, 9.5% female, and 2% without assigned gender. While either way these data are examined shows that works by female artists do not make up even 10% of the collection, what I thought would be more interesting consider is if there had been an increase in the acquisitions of art by women. I hypothesized that though the data here show a bias at the collection level toward males, presumably white males, there would be an observable historical trend toward increasing the number of women artists. Once I ran the numbers, I was able to confirm this hypothesis as you can see in Graph 1 below.

| Period | Date Range | Total Acquisitions | by male artists | by female artists | % by female artists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 1823-1864 | 3811129 | 38111 | 0 | 0.000% |

| 2 | 1864-1888 | 1257 | 1256 | 1 | 0.079% |

| 3 | 1889-1913 | 916 | 910 | 6 | 0.651% |

| 4 | 1914-1938 | 1787 | 1715 | 72 | 3.873% |

| 5 | 1939-1963 | 1540 | 1403 | 137 | 8.169% |

| 6 | 1964-1988 | 11019 | 10277 | 742 | 6.309% |

| 7 | 1989-2013 | 11101 | 9334 | 1767 | 13.732% |

Table 4. Data in Graph 1

According to the data in the object file, the year of the Tate’s first acquisition was 1823. The first object created by a female artist in the file is listed as being acquisitioned in 186830, and the second not until 1890. However, the data and graphic above does show a marked increase in the percentage of objects created by female artists especially in the last 25 years. From the original acquisitions to the last 25 year period, the percentage of objects created by female artist increase from 0.000% to 13.732%.31

Conclusions

The finding from the Tate is not at all surprising. In April 2019 a study was released based on the collections data of 18 major art museums in the United States. It found that over all of those institutions “85% of the artists are white and 87% of them are men”.32 This study is part of the larger recent discussion surrounding gender bias in art institutions33; The Baltimore Museum of Art recently announced that it will only buy art from female artists for their permanent collection in 202034; and there is software in development by Mujeres en las Artes Visuales, a Spanish Advocacy group, that will allow Museums to examine and quantify gender and racial bias within their collections.35 However, all of these efforts are looking at the world through the lens of heteronormativity. If the Tate’s nomenclature only includes the binary male/female or else leaving the field blank, that nomenclature is biased, as is any institution that includes gender as a metadata field and does not include an expanded vocabulary.36

Looking at heteronormative bias brings up a fairly large set of issues associated with finding bias in collections data. The data that would allow for determining bias against artists who are non-binary, or are not heterosexual, or even are ethically non-monogamous (which is also part of heteronormative patriarchal bias)37 is not data that was recorded in artist files in the past and is not always information that people are willing to share with a broad audience. So, then the first question is: should GLAM institutions collect this information from living creators and make it part of the data record? And if they do, how should that data be stored? Should that data be open access, or should it only be for institutional use and shared as statistical information? And really, if the bias doesn’t already show in the data, should the data be made to show it? As Frances Lloyd-Baynes says in her article “Documenting Diversity: How should museums identify art and artists?”:

“Isn’t pinning down someone’s gender/ race/ ethnicity/ sexual orientation playing to the same old biases we’re trying to divest from our practice? Yes, quite possibly. But as we collectively make the transition from unconsciously biased to an open, non-racist/-sexist/-genderist society, it does help us identify the problem and work to balance the scales.” 38

Notes

- This statement is based on a project for a previous class on Digitization and Digital asset management. My paper for that project can be read here: Guinan-Wiley, Cristin “Taxonomies and Card Sorts” Google Drive, April 2019 http://bit.ly/37PtJDN ↩

- Michelle Caswell, “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Stanpoint Appraisal.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3 (2020 Pre-Print)( 2019) https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/113. ↩

- Trienka Rohrbach (Owner), “iPres 2019 Collaborative Notes for Keynote 2 Michelle Caswell ‘Whose Digital Preservation? Locating our Standpoints to Reallocate Resources_._’” Google Docs, September 18, 2019 http://bit.ly/2kQroFb. ↩

- As Michelle Caswell states in her paper “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Stanpoint Appraisal.” (endnote 4), “feminist standpoint epistemology unmasks “neutrality” for the masculinist and white supremacist positions it obfuscates.” So, while it may not highlight all issues in descriptive metadata it opens the door for viewing them. ↩

- Sharon Farnel and Sheila Laroque, “Decolonizing Description at the University of Alberta Libraries” _ERA: Education and Research Archive,i_April 24, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7939/R3FQ9QM1S ↩

- Fiona Cameron and Helena Robinson, “Digital Knowledgescapes: Cultural, Theoretical, Political, and Usage Issues Facing Museum Collection Databases in a Digital Epoch,” in Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, ed.s Fiona Cameron and Sarah Kenderdine, 165–92. (Boston, Massachusets and London, England: The MIT Press, 2007). ↩

- GSISC 2020 Organizing Committee, “GSISC 2020: Technologies and Race, Gender, Sexuality, and the Body in Information Studies”. Litwin Books & Library Juice Press https://litwinbooks.com/colloquia/gsisc-2020/ ↩

- Kieth D Foote, “A Brief History of Metadata.” DATAVERSITY. February 28, 2019. https://www.dataversity.net/a-brief-history-of-metadata/#. ↩

- David Griffel and Stuart Mcintosh, ADMINS-A Progress Report (Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1967) http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/82974 ↩

- To view this metadata in Google mail services, click on the three vertical dots next to the reply button in an open email and select “Show Original”. There is a large body of writing in the legal realm based around the ethics of the usage of this metadata. ↩

- Carter, Todd, Josh Wiggans and Sally Hubbard “Automated Metadata,” Digital Asset Symposium June 26, 2017 http://www.digitalassetsymposium.com/2017/06/26/automated-metadata/ ↩

- For an excellent list of current metadata standards and standardized vocabularies please see the online appendices for Marcia Lei Zeng and Jian Qin, Metadata, 2nd Ed. (Chicago, Neal-Schuman, 2016). http://www.metadataetc.org/book-website2nd/index.html ↩

- Murtha Baca ed., Introduction to Metadata 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008) Also available in an online version at https://www.getty.edu/publications/intrometadata/ ↩

- Sharon Farnel and Sheila Laroque, “Decolonizing Description at the University of Alberta Libraries” ERA: Education and Research Archive, April 24, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7939/R3FQ9QM1S ↩

- MAIN-LCSH Working Group, “Indigenous Knowledge Management: Indigenous Subject Headings, University of Manitoba Libraries, Last Update August 15, 2017 https://libguides.lib.umanitoba.ca/c.php?g=45556 ↩

- “Research”, University of Manitoba Libraries https://umanitoba.ca/centres/mamawipawin/research/1182.html ↩

- Shawna Ferris and Danielle Allard, “Tagging for activist ends and strategic ephemerality: creating the Sex Work Database as an activist digital archive” Feminist Media Studies 2016 16:2 (2016):p194 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1118396 ↩

- Lizzie Smith, “Dehumanising sex workers: what’s ‘prostitute’ got to do with it” The Conversation, July 29, 2013 http://theconversation.com/dehumanising-sex-workers-whats-prostitute-got-to-do-with-it-16444 ↩

- Ferris and Allard, “Tagging for activist ends and strategic ephemerality: creating the Sex Work Database as an activist digital archive”, p195. ↩

- Fiona Cameron and Helena Robinson, “Digital Knowledgescapes: Cultural, Theoretical, Political, and Usage Issues Facing Museum Collection Databases in a Digital Epoch,” in Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, ed.s Fiona Cameron and Sarah Kenderdine, 165–92. (Boston, Massachusets and London, England: The MIT Press, 2007). P172 ↩

- Douglas McCarthy and Dr. Andrea Wallace, “Survey of GLAM open access policy and practice” Google Sheets 2018 to present, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit?usp=sharing. ↩

- Mia Ridge ed., “Museum APIs” Museums and the machine-processable web, Last edit September 13, 2018, http://museum-api.pbworks.com/w/page/21933420/Museum%C2%A0APIs ↩

- Luda Zhao, Brian Do, and Karen Wang, “SherlockNet data” British Library Research Repository BETA, 2017 https://bl.iro.bl.uk/work/3205f8c5-f7dd-46fa-8bf4-9ac72f6fbb55 ↩

- British Library, “Image taken from page 46 of ‘Songes and Sonettes’ Flickr December 5, 2013. https://flic.kr/p/i6oCBR ↩

- Tate Gallery, “tategallery/collection” GitHub data set last updated October 2014 https://github.com/tategallery/collection ↩

- Florian Kräutli, Visualising Cultural Data: Exploring Digital Collections Through Timeline Visualisations. PhD Thesis. London: Royal College of Art http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1774 ↩

- Florian Kräutli, “The Tate Collection on GitHub” YYYY-MM-DD Time/Data/Visualisation November 2013 http://research.kraeutli.com/index.php/2013/11/the-tate-collection-on-github/ ↩

- The Tate did not open until 1897 and the first works that were in it’s collection were the 65 works that Henry Tate gave to the museum in 1897. It appears that all works whose acquisition predate 1894 were transferred to the Tate at a later time. It is interesting that the acquisition date did not change with the transfer. The Tate, “History of Tate”, Tate no date https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/history-tate ↩

- The vast majority of these acquisitions were “Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856” as stated in the credit line column of the object file. ↩

- This work was actually presented to the National Gallery in 1868 and transferred to the Tate in the 1920s. Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.84-5, reproduced p.84 http://bit.ly/33y3z5g ↩

- What the previous three footnotes highlight is that data is awesome but may require additional context depending upon what you are looking for. ↩

- Chad Topaz, Bernhard Klingenberg, Daniel Turek, Brianna Heggeseth, Pamela Harris, Julie Blackwood , et al., (2019) “Diversity of artists in major U.S. museums”. PLOS ONE 14(3) March 20, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212852 ↩

- It is interesting to note that this is not just a conversation happening surrounding art museums but also in Natural History Collections : Graham Gower, et al, “Widespread male sex bias in mammal fossil and museum collections” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Sep 2019, 116 (38) 19019-19024; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903275116 AND Natalie Cooper, et al, “Sex biases in bird and mammal natural history collections” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences October 16, 2019, 286 (1913); https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2025 ↩

- Mary Carol McCauley, “Baltimore Museum of Art will only acquire works from women next year: ‘You have to do something radical’” The Baltimore Sun, November 15, 2019 https://www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/arts/bs-fe-bma-female-artists-2020-20191115-33s5hjjnqfghzhmwkt7dqbargq-story.html ↩

- Artforum Staff, “New Software Tracks Gender Gap in Museum Collections” Artforum, November 15, 2019. https://www.artforum.com/news/new-software-tracks-gender-gap-in-museum-collections-81308 ↩

- Of great help to any GLAM institution if they wish to move away from the heteronormative bias is the Homosaurus. Which was created to be used in conjunction with other subject term vocabularies. Homosaurus Editorial Board, “The Homosaurus v2” Homosaurus May 2019 http://homosaurus.org/ ↩

- Gayle S. Rubin, “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality” in Culture, Society and Sexuality A Reader, eds. Richard Parker and Peter Aggleton (London, Routlidge, 2007) http://sites.middlebury.edu/sexandsociety/files/2015/01/Rubin-Thinking-Sex.pdf ↩

- Frances Lloyd-Baynes, “Documenting Diversity How should museums identify art and artists?” Medium: Minneapolis Institute of Art March 27, 2019. https://medium.com/minneapolis-institute-of-art/documenting-diversity-17f55a4118da ↩