Chapter 11. Slow Change

- Clare Brown

- Isabella Bruno

Isabella: On my way to Museums and the Computer Network 2018, I read Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary by Dan Hill. The conference was a reset and reflective experience. As a new Smithsonian employee for almost a year, I was wrestling with its vastness. I talked incessantly to many people at the conference about Hill’s ideas on stability and strategy at institutional scale.

Then the government shutdown of 2019 closed Smithsonian museums for four weeks.

Clare Brown and Isabella Bruno: During the furlough we sat down to consider strategic design in museum contexts by discussing the book. Although most museum employees may not be subject to the federal bureaucracies as in the Smithsonian Institution, it is not a far stretch to draw broad connections to the outdated organizational structures, processes, communication methods, and workflow infrastructures that many museums perpetuate despite progress and evolution that has happened outside the museum sector. Dark Matter and Trojan Horses focuses on strategic design within large-scale organizations and projects. Hill explores the notion of “dark matter” as the intangible, invisible systems and cultures which bind organizations together. This dark matter creates sticky problems but it can also be used as a lubricant to help untangle those same sticky problems.

The following chapter, drawn from recorded dialogue, edited for clarity, addresses relevance between Dark Matter and Trojan Horses and the museum context by asking: What is strategic design? Why strategic design for museums? How we can make practical use of strategic design within the museum context?

For both of us, museum process is vital to the outcome of the work we do. Underpinning our daily efforts is an understanding that the modes by which we work affect the products we create. Without explicitly referring to it, Dan Hill builds a thread of arguments that are closely aligned to what is known as “Conway’s Law.”

Clare: I’m particularly interested in Conway’s Law because it’s the relationship between how something’s made and what the effect of that is on the end product. Conway’s law is: “Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”1 It has been a focus of mine to draw a connection between Conway’s Law and museum practice, in order to evolve the methods by which we work together to produce visitor experiences.

Isabella: I’ll read a quote from the book. Dan Hill writes “the user is rarely aware of the organizational context that produces a product, service, or artifact, yet the outcome is directly affected by it.”2 Not just communication structure, it could also be expanded to power structures. Toyota subverted the traditional top-down factory hierarchy by introducing the “andon” cord (now wireless button). Workers pull the cord to alert co-workers when a problem crops up so they can get help. If the glitch persists, workers may even stop the line to troubleshoot.The cords are essential to Toyota’s concept of built-in quality, or catching problems before they head down the line. There, issues don’t have to swim upstream against the flow of communication. In contrast to environments where pointing out what a boss hasn’t prioritized inherently undermines organizational hierarchy. Toyota made quality a truly shared responsibility, so mission-critical that it could stop the factory floor.

Clare: Our communication structures, organizational structure, team formation and project management directly affect what we’re creating. That is a top-down way of applying Conway’s Law. What if we reversed Conway’s Law and start with the user experience of the product—or in our case—the visitor’s perspective? Visitors assume that everything they experience in the museums is planned and synchronized; what if our organization was structured with an org chart and operating system to mirror the visitor experience? And so why aren’t we creating our offerings as a considered whole? I’ve been thinking a lot about Hill’s emphasis on “operating system.” An operating system needs to have a relationship to the intended operations as a whole, right? You don’t want an operating system that creates something that has no connection to, or bearing on what it is you’re trying to do. My view is that many museums have operating systems that are not aligned to the operational goal.

Isabella: In the tech world, I think Conway’s Law has been used to encourage smaller teams to work iteratively, agilely and somewhat independently, but there’s been pushback over time. Small teams often end up having allegiance to their members over organizational goals. So I’ve noticed more talk about platforms and microservices as a way to distribute the codebase and encourage more autonomy. Even the term operating system implies that there’s some master creator somewhere that created it. And God knows that that’s why there’s dark matter. Because we haven’t yet considered the creation of this system that we operate within. Which leads us to: what is strategic design? How might museums use it?

Clare: Strategic design is a way to approach wicked problems which are tangled networked problems. Dark matter would be the stuff between all those tangles. Museums, whether they are government museums or not, local, experimental museums, art galleries, or public art museums; all have this weird, non corporate, but also “non” nonprofit way of working and complex, networked, organizational and operational problems. We have problems with how to manage collections, storage space, staffing, we are short on money, we pay our people poorly. We have major disconnects between the goals and values of disciplines across museum functions. All of this results in major morale issues—something I hear repeated among museum colleagues both across the USA and in the UK and Canada. We hear this in conferences, too, where numerous sessions are devoted to discussing problems in process and museum culture. Interestingly though, it is rare to hear these discussions move past day to day issues or siloed issues. This is why strategic design seems so necessary in the museum field.

Isabella: Hill proposes that governments need strategic design because they are “18th century institutions underpinned by philosophies and cultures having a similar vintage, now facing 21st century problems.”3 That’s two centuries removed! This applies to public institutions, large bureaucratic governmental entities, and the wicked problems of healthcare and education, these large, broad, sweeping societal structures. As Hill says: “The dark matter of strategic designers is organisational culture, policy environments, market mechanisms, legislation, finance models and other incentives, governance structures, tradition and habits, local culture and national identity, the habitats, situations and events that decisions are produced within.”4 So we know our context applies, but as a skill set, is strategic design just for designers? It’s got the word design in it. Who is it for? Who can use it?

Clare: That’s a good question. Hill spends a lot of time talking about the role of designers and is somewhat disparaging about external designers (consultancy design) versus internal. He emphasizes the downfall of “design thinking,” corporatized and systematized in a way that simplifies design too far. He laments the trend of simplifying design thinking to something like ‘ten easy steps that you can learn on YouTube’ where anybody can be a designer.

Isabella: External designers don’t have to live with the reality of implementing their work. It can become a situation in which someone pops by and leaves half-formed tools that sound great but are actually unusable. Or, the organization rejects some recommendations and implements others which leads to lopsided results.

Clare: Yes! What an unfortunate waste of time and money for organizations that are desperate for workable solutions. In addition to discussing the pitfalls of external designers, Hill also expresses concern about the disadvantaged position many internal designers are in. He talks about the importance of design stewardship—fostering and caring for what is intrinsically good in the practice—something that only in-house designers can do for an organization. But he also explains why it is difficult to be a design steward when the organizational and operational system doesn’t include the designer to the best advantage.

Isabella: Designers aren’t invited to contribute to planning or strategy. Since that’s where operation and hierarchy is established, design is in a position that cannot “exert the strategic value inherent in design.”5 We are embedded, but not empowered to share our observations that emerge from our cross-disciplinary, non-linear work.

Clare: He is saying a strategic design gets into the dark matter. But what about the barriers between designers in this business planning and organization? How can we really get at the dark matter? Except covertly, insidiously, but not directly?

It’s interesting that Dan Hill is a strategic designer, employed by and embedded within the Finnish government. His use of the word embedded is how journalists are placed in Afghanistan—where they are placed within the situation in order to observe and report about the situation.

Isabella: Dan Hill’s role is unique because he is both a part of the agency and also coming in as an authority at the same time.

Clare: I think it would be worth breaking this language into two: embedded and native. Native designers are the ones who suffer from being part of the original organization because they are pigeon-holed into roles and systems that don’t maximize their abilities. Embedded designers are deployed or deputized to an organization to observe, maintain perspective, and suggest improvements in roles and systems.

Even as native designers we do have perspective… in fact, it is the strength of all designers to have perspective. Our perspective comes from the fact that we are not subjects specialists in the topics around which we design. We have to maintain the ability to work across projects, across multiple teams, and we see connections because we don’t have our heads buried in singular efforts. The challenge that designers have in museums is that we are brought in as technicians to implement what other people want us to do, not because of our strategic abilities. What happens if the question being asked is not the right question? We’re not in a position—like Hill is—to make report on our observations in an effort to make strategic change. The problem is that the word “design” is misunderstood, undervalued and misplaced in the museum.

Isabella: I would say that this is probably something that a lot of roles in the museum feel—the value of their role is misidentified. Every profession has gone through a period where their only selling point is the product they deliver. An evolution is necessary for their processing value to catch up to their output value. And it’s not a smooth evolution from “Oh, well, the designer’s value is their knowledge of the production process,” to “designers have actual ideas,” and then “designers will be able to talk to people who weren’t in the room about the ideas.” The definition of value and ability to recognize it expands over time. Once, graphic designer just meant typesetter, not person who deeply understands visual communication. I hope that evolution happens for all roles in museums. Look at what’s just happened with the recent conservation efforts for the NMAH pair of Ruby Slippers from the Wizard of Oz. Our conservators were not just technicians, but their forensic vantage point aided in cracking an FBI case for a stolen, then recovered, pair.6 That’s more than a wonderful human interest story, it helps me understand more about what conservation is and can do.

Clare: In order to affect strategic change through strategic design, and the way he described it, it would not be isolated to your own department. It would have to be people who are able to see across divisions. Exhibition designers are uniquely positioned in the same way that collections managers are, because we’re not project specific. We are also completely connected to the audience. We move inside and outside of the museum, and across.

Isabella: Reporting structure can be a barrier when it doesn’t recognize the overlaps between project types or teams and reward our ability to move successfully between different spheres of knowledge. We context shift as we move between projects. It falls upon the shoulders of each member of the project to translate from one domain or sphere of knowledge into his or her own. And conversely, from his or her own into that of another sphere. As a clarifying example, no one would ever expect to pass unclear plans or expectations to a team of fabricators, and yet we don’t think twice about passing half-baked information between educators, curators, designers, etc without a similar rigor. We are missing the benefits of distributed work and network redundancy. We could lower our risk by accepting that knowledge cannot be siloed, if our work is not. To paraphrase from Michael Lewis’ The Fifth Risk, the burden of education doesn’t fall only on the Department of Education—it’s the county, the parents, the transportation system, the health board, it’s everything that makes school possible.7 Hill has a metaphor about a building in which many systems run simultaneously, relational but not dependent. Some systems can change faster than others, but slowness of changing all systems isn’t obstinance, it’s stability. It’s why microservices are the new hot thing as distributed, independently deployable applications. It’s why government carries risk (nuclear waste storage, superfund clean-up, etc.) that the for-profit world cannot or will not take on. Our time frames are so long (in perpetuity!) the biggest risk seems more likely to be not actively listening, responding to situations and people. We struggle with the soft skills.

Clare: While Dan Hill’s case studies were interesting and relevant to museums, I would love to have more practical ways for us to improve our position as native designers. Like curling, we need a person with a brush in front of the stone. One of the ideas we had after furlough—when we came back fresh and ready to roll—was a rubric for a soft skills role, as we called it a “project doula.” A team member would provide guidance and support for team-mates as they “labor.” We thought shifting the role between the team builds empathy and consideration to others’ needs.

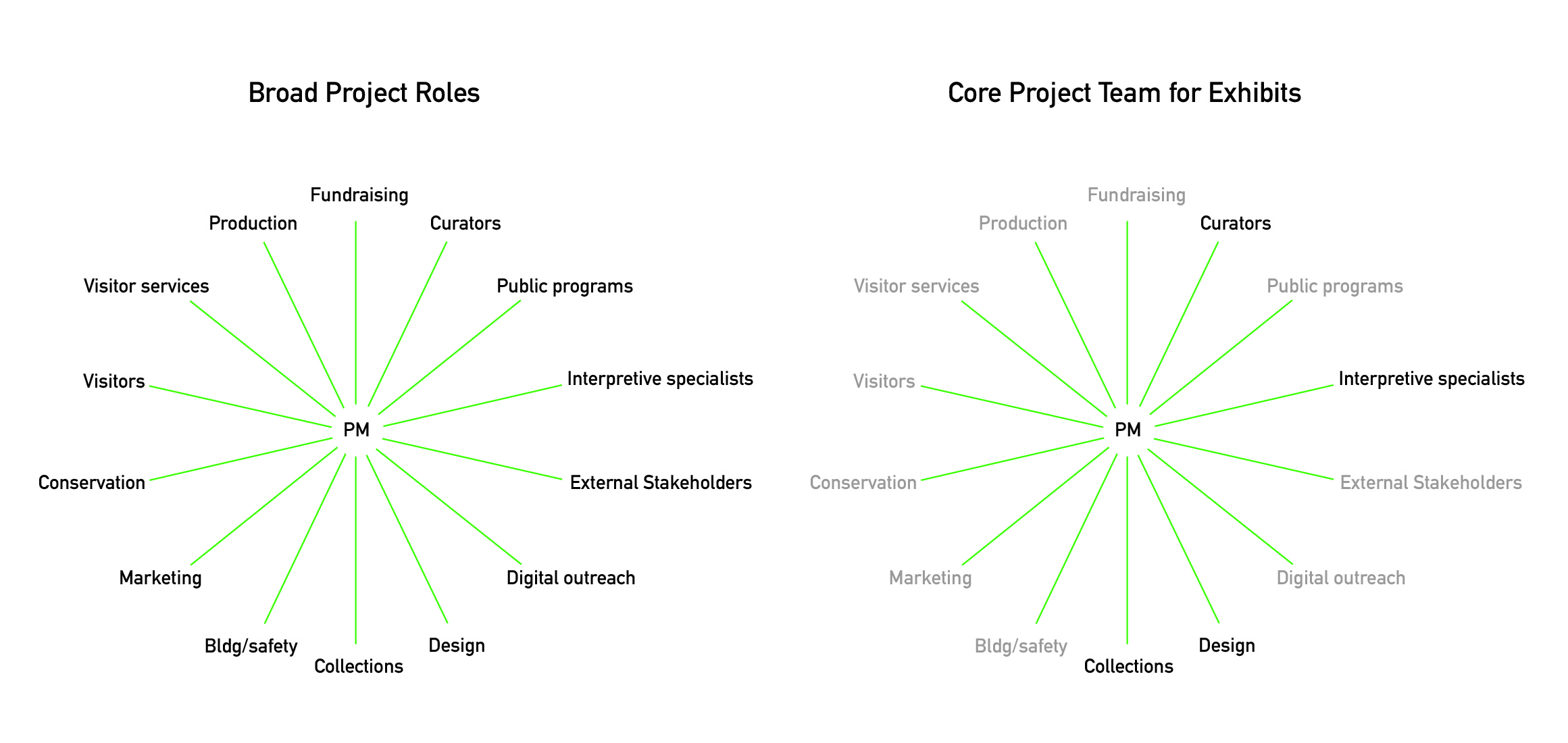

Isabella: After illustrating team relationships in spoke and hub diagrams, we saw how easy it was to leave out related staff and stakeholders from team formation.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Clare: And importantly, the visitor consistently was not considered part of the project team.

Isabella: And definitely not Congress! Diagramming who is on a project and noting core and supporting team members exposes our dark matter. Take supporting team members out of the diagram to simplify it and those people disappear. How can we create tools that encourage conscientiousness? In The Art of Gathering, Priya Parker talks about by defining the walls of the gathering, but not inviting everyone in; it actually allows us to metaphorically “close the door” and create a safe space for intimacy.8 Excluding some people is better that inviting everyone. It allows you to bring individuals conscientiously when needed and with purpose, not default to a “committee of everyone.” We can create the room and still have a democratic process that allows for movement in and out of the project.

Clare: I like the idea of a project doula reporting out on behalf of you, like a mediation tool. Like a post it note exercise where you ask a question and then you introduce that person to the team: you have to get to know the person in order to speak on their behalf. In Developmental Evaluation, Michael Quinn Patton proposes having a new role—developmental evaluator— who reports to the team what’s happening within the team and is the emotional barometer of team health.9 Processes in which we get to know each other and understand individual needs help with the untangling of a wicked problem. Authentic connection unearths dark matter in ways that are not limited to direct questioning but can use intuition and soft skills to find deeper insights.

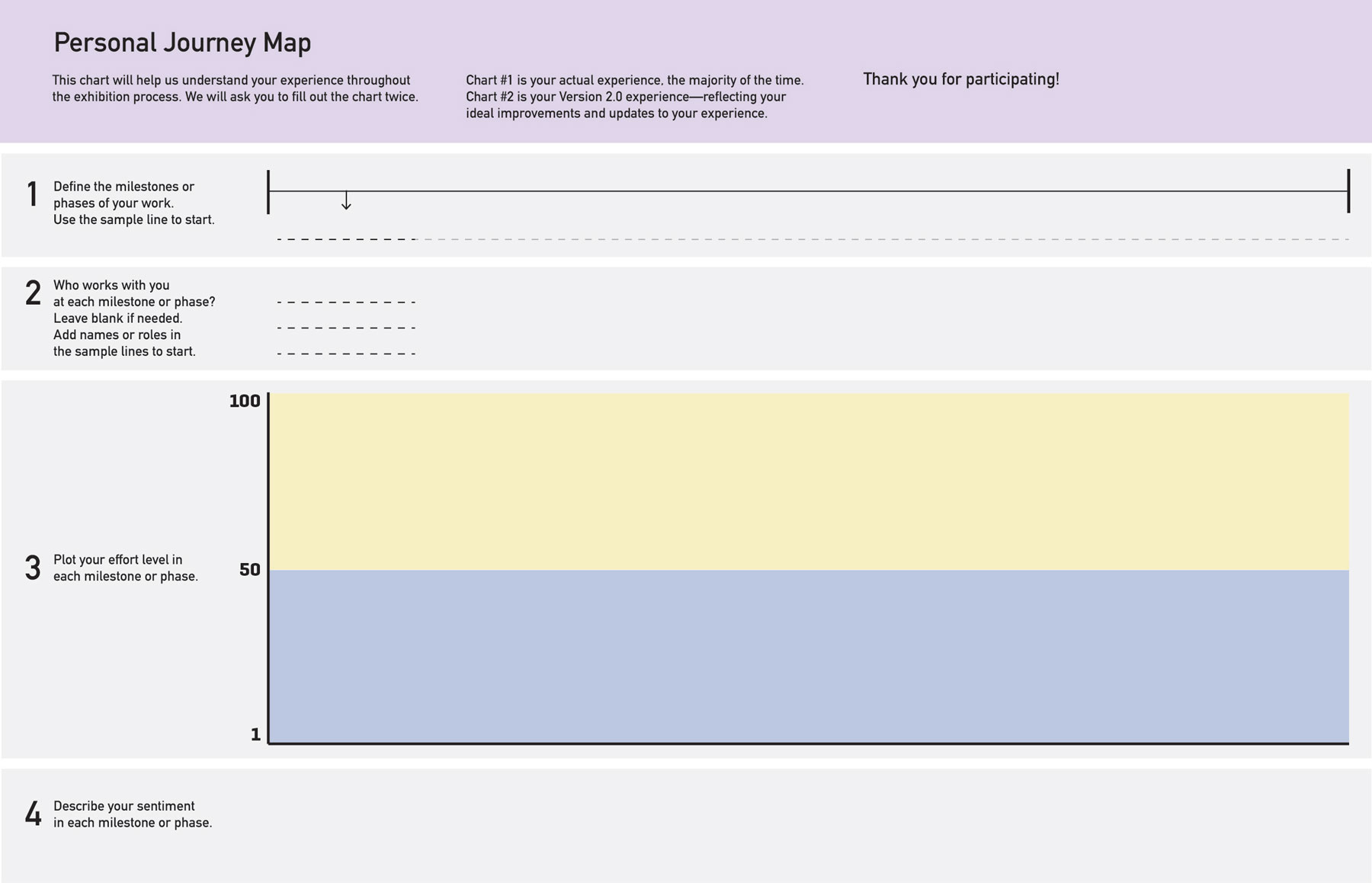

Isabella: As we talked through this project doula idea, we wondered if we could just listen and document the people we’re referring to as opposed to just bring in another wrench to see if it fit the problem. This became a “Personal Journey Map” that asks participants to identify their work steps during exhibition-making, who collaborates or works with them in each step, then their effort level and finally their sentiment. And we are using this to interview 70+ staff, curators, production, conservators, visitor services, public programs, social media, finance, fundraising and more. The result paints this unbelievably rich picture of different roles, experiences with exhibition-making across the museum… and areas for improvement.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Clare: Because we’ve gone very broad with who we’re asking to do the journey maps, we’re extending on both sides the timeline of an exhibition-making process beyond what we assume it to be. For instance, I talked to someone who works on collateral that’s related to the exhibitions and her timeline was so very different than anything I experience. I also spoke with procurement staff who I see as integral to the success of an exhibition (we need supplies for fabrication!), but they don’t see their daily work as exhibition-related.

Isabella: We realized that we should probably talk to volunteers and docents, who don’t technically have any relationship with exhibition making, but they definitely have a relationship with the visitor experience of an exhibition on the floor. So they’re doing their own exhibition making in their interactions with those visitors.

Clare: If we think of the exhibition making as what the visitor perceives, front-line staff aren’t only representing the museum, they ARE the museum. Our “Personal Journey Map” project is actually a really good ‘How to do strategic design’ because it is revealing dark matter as we go.

Isabella: And within the limits of our agency. We can’t deny that we’re milking everything we’ve got in our current roles by doing these interviews. How we apply strategic design can extend beyond the boundaries of what we think “our work” looks like. We tend to think we’re a lot more rational than we really are. But we’re not 100% rational, we are emotional, intuitive and many other things. We deserve to bring more of our full, human selves to work. I recently learned of a ritual design practice which has created a funeral to mourn a downsized department for a company.10 That sounds incredibly strange, powerful and bonding. I’ll be really happy the day that I can do interpretive dances in order to communicate exhibition design concepts. I hope we can become open to different modes of communication, using metaphors that tap into diverse experiences that we are each having internally and externally, because just writing memos and grouping post-its isn’t enough.

Clare and Isabella: Our conversation ended here but we continue to ask ourselves how we can be strategic designers and bring holistic thinking into our practice and internal culture. We wonder if we can share our design skills outside of our silos (which prevent lateral communication) and across hierarchies (which prevent communication going up when it flows down so well). Can we overtly create networks and lower risk within our organization by strategically working for others’ ROI (return on investment)? Would that reciprocate in building trust in strategic design and expand our trust in each other and in our shared mission? We intend to find out.

Notes

- Melvin E. Conway, “How Do Committees Invent?,” Datamation, April 1968. ↩

- Dan Hill, Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, (Moscow, Russia: Strelka Press, 2014). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Griffin, Julia, “How the Smithsonian Helped the FBI in the Case of Stolen Ruby Slippers,” PBS. October 19, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/how-the-smithsonian-helped-the-fbi-in-the-case-of-stolen-ruby-slippers, (accessed January 4, 2019). ↩

- Michael Lewis, The Fifth Risk, (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018). ↩

- Priya Parker, The Art of Gathering, (New York City, NY: Riverhead Books, 2018). ↩

- Michael Quinn Patton, Developmental Evaluation, (New York City, NY: Guilford Press, 2010). ↩

- Kursat Ozenc and Margaret Hagan, Ritual Design Lab, https://www.ritualdesignlab.org (accessed January 10, 2019). ↩

Bibliography

- Conway, Melvin E. “How Do Committees Invent?,” Datamation, April 1968.

- Hill, Dan. Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Moscow, Russia: Strelka Press, 2014.

- Lewis, Michael. The Fifth Risk. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

- Ozenc, Kursat, and Margaret Hagan. Ritual Design Lab. https://www.ritualdesignlab.org (accessed January 10, 2019).

- Parker, Priya. The Art of Gathering. New York, NY: Riverhead Books, 2018.

- Patton, Michael Quinn. Developmental Evaluation. New York City, NY: Guilford Press, 2010.