Chapter 7. Performing the Museum: Applying a Visitor-Centered Approach to Strategy, Experience and Interactions

- Seema Rao

- Jim Fishwick

- Alli Burness

Just as gender and identity are performative for individuals, so too is the institutional act of ‘being’ a museum through programming, interpretation and communications. Authentic, relevant and accessible exchanges require meeting people where they are, connecting with visitors personally, understanding the communication tropes they use and their definition of what art or culture may be to them. This chapter is speculative in that we explore the performative museum as a concept and discuss methods to apply it within organizations. First, we discuss the concept at a theoretical and strategic level by focussing on the values that museums can realise as an outcome. Then, we explore how the concept can manifest as a unified and felt experience through signage and behavioural rules that clearly articulate the museum’s values to visitors. Lastly, we outline some practical improvisation techniques that can be used to flexibly build interactions with visitors and achieve empathy in an organization’s body language.

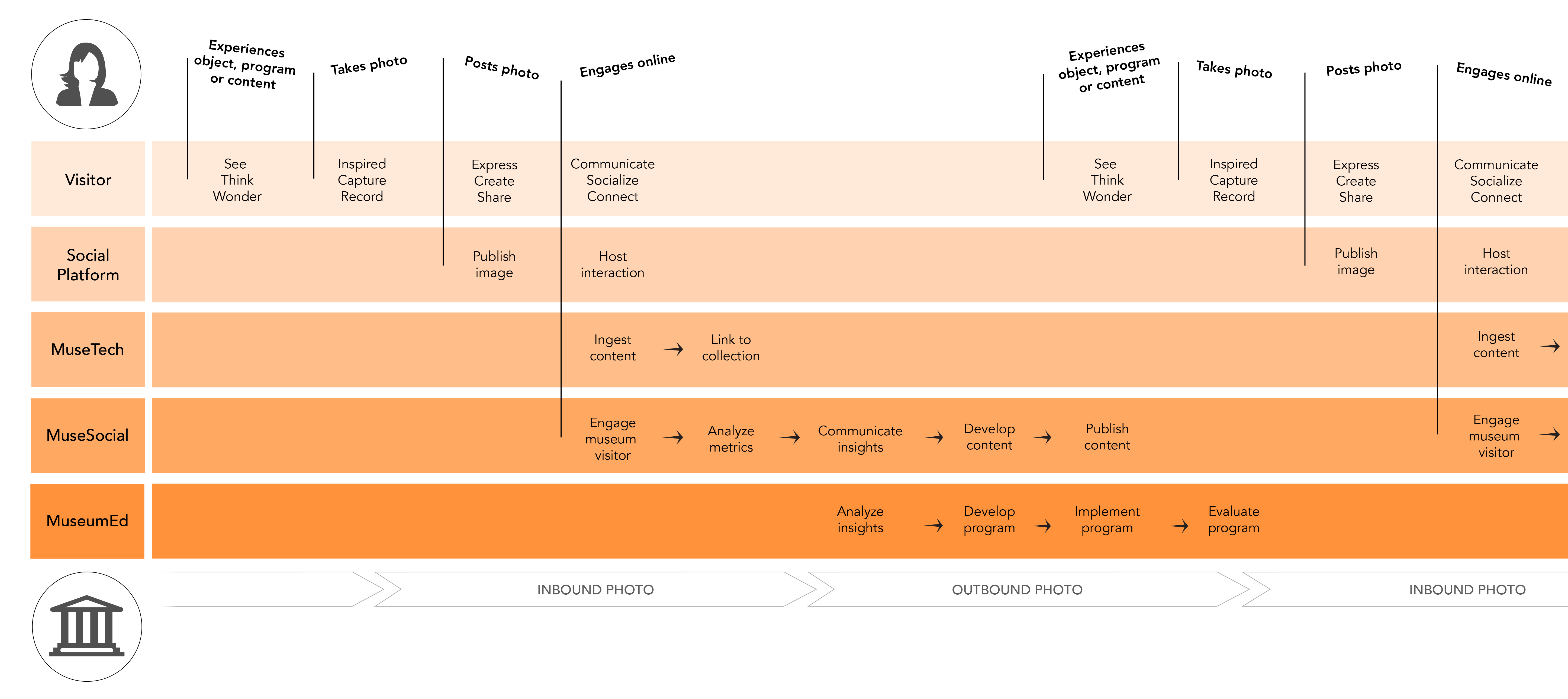

The concepts underlying this work grew from a presentation at the 2016 Museum Computer Network conference by a group of museum professionals exploring the impact of visitor social photography on the museum. Alli Burness, Jenny Kidd, Megan Estep and Chad Weinard took inspiration from in-progress research examining datasets of Instagram images taken by visitors to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Australia and similar research conducted at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar.1 The authors of both sets of research emphasized that social photography can allow visitors to express their agency and authority through sharing their embodied experiences of museums. At its heart, the framework developed by Burness, Kidd, Estep and Weinard defined the museum as a relationship between an organization and its visitors (Figure 1).2

Figure 1

Figure 1

Two years later, our understanding has deepened. We now believe the museum can be defined as a particular type of relationship. In this chapter, we argue that museums are sites of performative exchange created through interaction and emerge through the experience of ‘doing the museum’. In this way, museums can be reframed as performative rather than authoritative. They begin to exist when visitors interact with the museum and the museum interacts with visitors through organizational body language. While we argue for the performative museum in this chapter, we advocate against the museum as a performance and the rise of Instagram museums.3 The museum is created in the moment of an experience shared by an organization and the visitor, triggered by an interaction. This can then be expressed in the form of social photography but cannot be encapsulated within a photograph itself.

It is useful to understand the distinction between the terms ‘performance’ and ‘performativity’. A ‘performance’ is a noun. It is an act that can stand on its own. In contrast, ‘performativity’ is a concept that describes behaviours that are repeated. Judith Butler has defined this as “not a singular act, but a repetition and a ritual, which achieves its effects through its naturalisation in the context of a body.”4 By this we understand Butler to mean that a performative act is one that is constantly repeated, perhaps as a ritual that brings a religion to life, or a behaviour that brings an identity or social role into being. It is through performative acts that we construct our identities and social groups.

We can scale up Butler’s concept of individual performativity by applying Chris Flink’s concept of organizational body language.5 Flink refers to the power of the form, shape, functionality and aesthetics of a space to reflect values that have the ability to shape the experience of a person. By extension, the actions and behaviours of people who represent an organization extend that power. The grammar of a museum’s buildings, spaces, lighting, signage, furniture and labels create a stage on which the interactions, tone, voice and responsiveness of staff within it are performed. Together these form the organizational body language of a museum.

The performative museum is formed by repeatedly exchanging interactions with visitors that evolve the values and identity of both the visitor and the organization. This is a challenging concept, but it is gaining traction in the cultural sector. Research by Jay Rounds indicates that visitors use museums primarily for identity-work, or “the processes through which we construct, maintain, and adapt our sense of personal identity, and persuade other people to believe in that identity.”6 At Communicating the Museum conference in 2014, Kingsley Jayasekera described the museum as “a relationship between content and an audience.”7 In 2016, Alli Burness has laid theoretical groundwork that positions selfies taken in museums is a response to and form of self-expression inspired by museum objects.8 In 2018, James Bradburne marked the distinction between enacting a collection and holding objects in a collection.9 Increasingly, leaders in the cultural sector are understanding and articulating the performative nature of the museum and the ways in which this can be observed.

Intentionally applying the concept of the performative museum involves different approaches at the strategic, experiential and interactional levels. To effect such a change at a strategic level, we should understand where an organization is currently, where it needs to move to and how to get there. We can apply a type of design reasoning to this by seeing these as elements of an organization now, the outcome the organization is seeking to achieve and the pattern of relationships or interactions it uses to get there.10 How do these three settings in our reasoning need to shift to realise the performative museum?

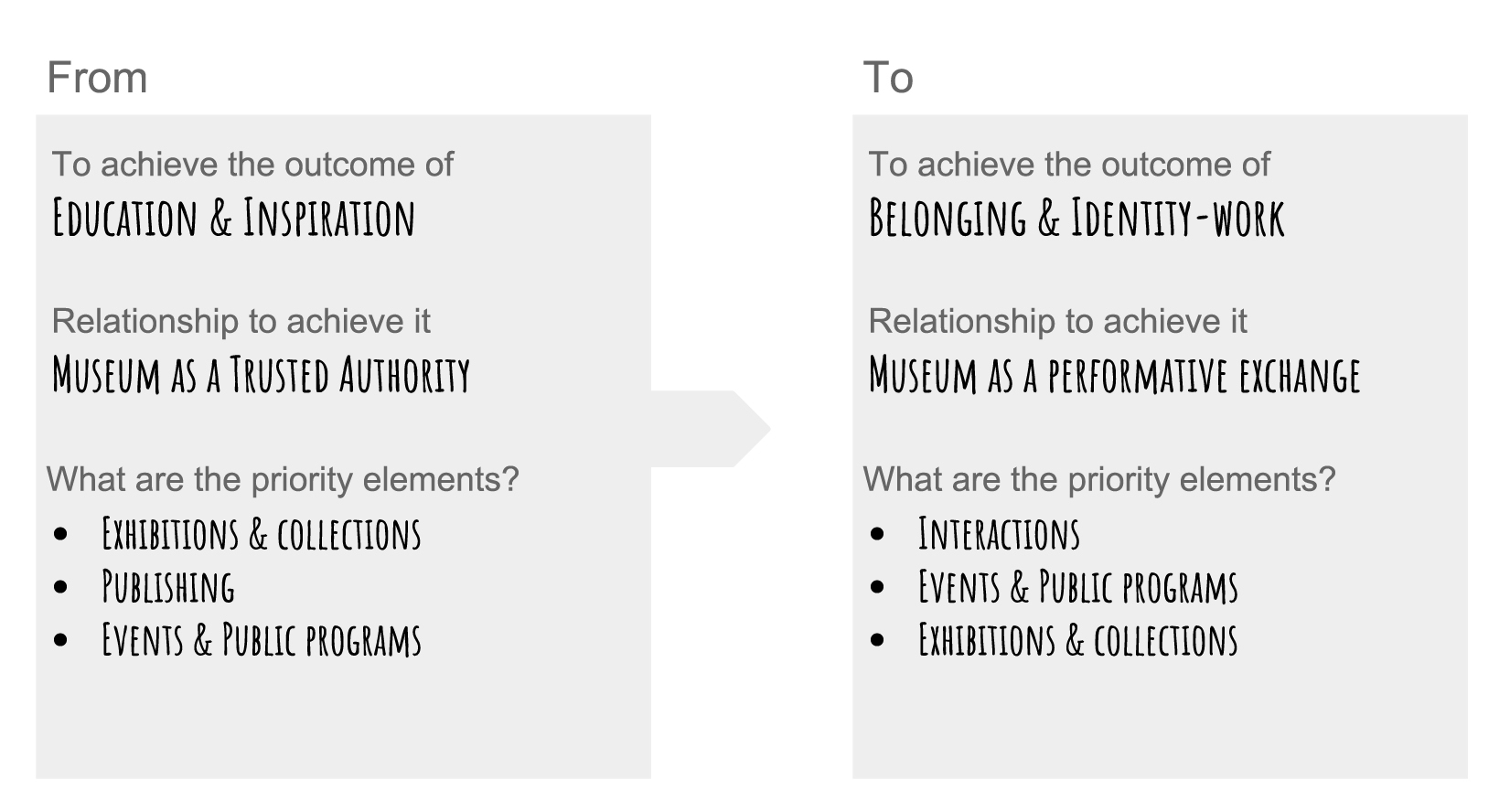

Our hypothesis in this chapter is that to achieve belonging and identity-work as a shared outcome for both visitors and the museum, we should reframe the relationship through which museums engage with visitors. The museum moves from a trusted authority that aims for educational and inspirational outcomes, to a performative relationship of exchange for the shared outcomes of belonging and identity work (Figure 2). It is this intentional outcome (the values of belonging and identity-work) that should be routinely enacted by the physical and digital infrastructure of a museum, as well as staff and visitors.

Figure 2

Figure 2

This reframing re-prioritises the activities, or elements, of a museum. Rather than focussing on exhibitions, collections or publications as means for disseminating information, the performative museum will leverage exhibitions, the collection or publications in service of experiences that facilitate interactions with visitors. Education and inspiration remain present, but in the performative museum, they work as sites of experience, as vehicles enabling interactions that build a sense of belonging.

If organizational values are shared with visitors, and the elements of experience that enact them are interconnected, their outcome can be powerfully achieved. However, the perception of an experience is often subliminal. Experience often only touches the conscious mind when errors or lapses occur. Who has not noticed a jarring element in a space, like the shining red exit sign in an elegant Victorian house museum? To become intuitive, experience requires systematic intentional thought to interconnect all the elements of an institution.

Good experience is easy to feel but sometimes hard to describe. In practice, experience requires strategic awareness and implementation, so every element is produced to stay in line with the organization’s cultural norms, philosophical underpinnings, and intended visitor experience. Said differently, all staff need to put in thought to the experience so visitors will feel the organization’s values, even if unconsciously. Ideally, every organization should articulate how their visitor should feel in their space. If we think of an organization as a system of decisions, the experience level is the benchmark against which all choices are made. An organization can decide their brand experience is relaxed curiosity, for example, based on their institutional values of education and lively learning. All choices from the font on signs to the types of programs would be measured against the defined experience.

Museums often overlook the simple task of articulating the quality of their intended experience and instead, are more focused on what the visitor should think. However, when visitor’s feelings are ignored, spaces leave visitors feeling cold or unwelcome and unable to think at all. By focusing on shared values, museums can build visitor needs and feelings into their work of connecting visitors with collections and community.

Physical space is the easiest way to consider experience. Signage is the most common site of experience dissonance in museums. It is often produced in design departments, with the text being determined by marketing or education. These departments, however, often ignore the feelings that such signs produce in visitors. Signs are then produced to follow the design norms of the institution. Art museums, particularly, institute subtle norms, in keeping with their near clinical spaces. Subtle signs work in spaces where the message is redundant, and users already know the information. For example, apartment buildings often place simple, subtle signs to remind inhabitants of garbage day. However, art museum patrons, in large part, don’t know the information in the signs. Consider the subtle ‘no food or drink the gallery’ signs that museums use during parties and late-night events. Staff are almost always stationed with those signs because no one reads them. Human nature certainly comes into play, in this case. However, the design of these signs is also to blame. Signs cannot communicate if they are produced to be hidden in plain sight.

When an unnamed museum created list of rules for an education and technology space, the decision was made to place these rules in white text on glass with the intention of maintaining the sanctity of the space. Explicitly articulated rules, it should be said, was a significant move by the museum towards improving visitor experience. Prior to that time, leadership staff had argued that posting the rules felt punitive. We argue museums have rules, posted or not. Implied rules are no less punitive and serve to support the general cultural inaccessibility that can plague such organizations. However, the unexpected message of producing signage in this manner was that the rules were unimportant. Spaces that want visitors to read the rules make them clear and legible.

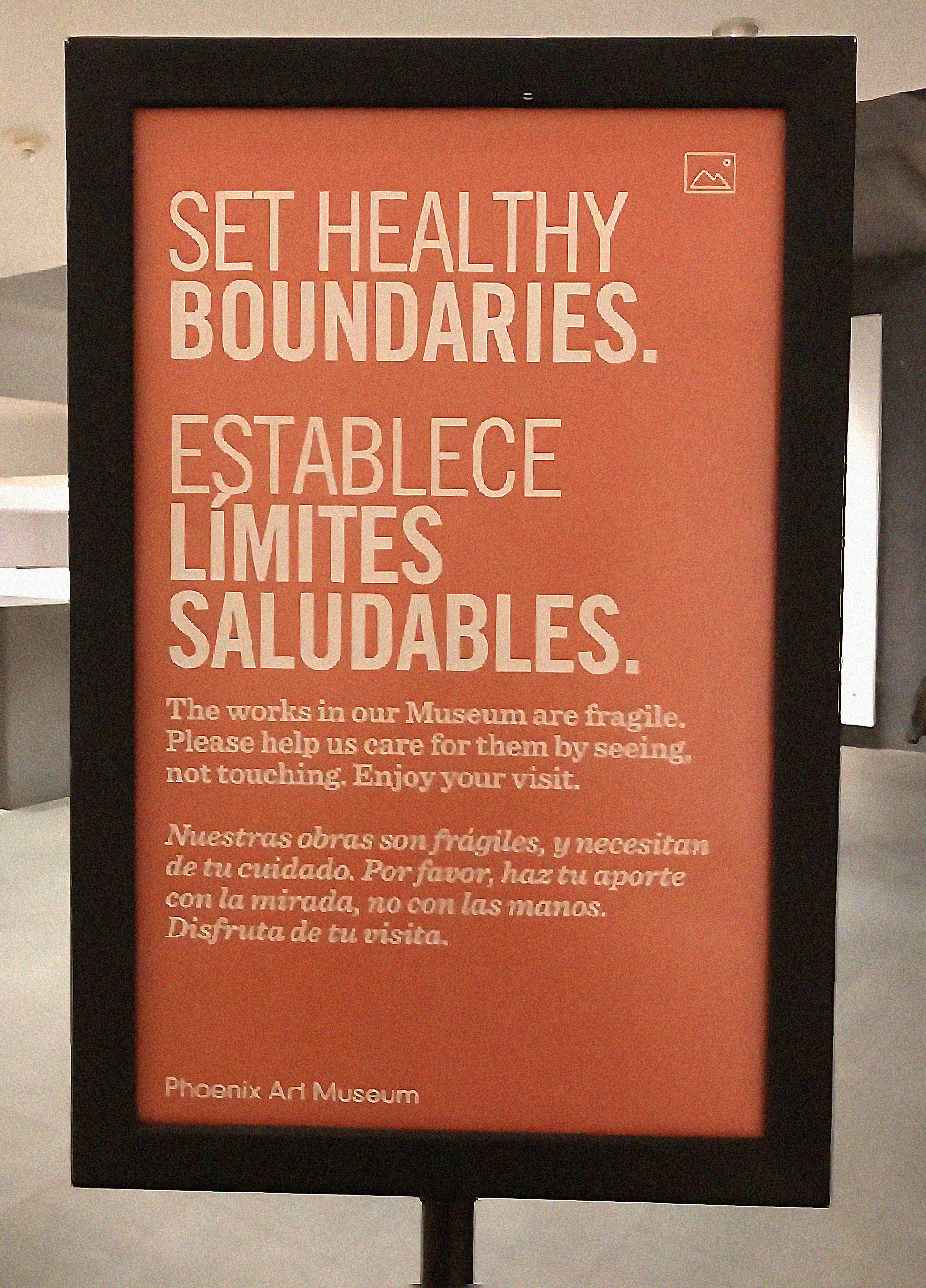

At the Phoenix Museum of Art, “Do Not Touch” signs are an example of placing the importance of the message over the unspoken rules of design (Figure 3). Produced in bright colors, their large stanchion signs were positioned throughout the galleries. The signs are notable not just for their placement in the center of galleries and for their appealing colors. The team at Phoenix Museum of Art took great effort to communicate not just the rules but the organization’s attitude toward patrons with open, inviting language. These signs are a stellar example of an organization working across silos to deliver a unified experience to patrons as manifest in physical artifacts of the space, in this case, a sign.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Spaces and signage are some of the easiest ways for organizations to improve the experience level. However, for visitors, the experience level is most apparent in interactions with staff. Any person going to Disney World or a similar leisure space intuitively understands their staff interactions in delivering elements of the experience level. The staff have specific codified behavioral norms. While museums might not want to be as circumscribed as corporate experiences, the idea of developing norms for visitor experience is rare in museums. Front of house staff are the greatest ambassadors if museums take the effort to leverage their skills and powerful position in meaningful visitor experience.

There are lots of ways that interactions might be mediated as part of a museum experience. These could include a public program, an exhibition, front-of-house staff or a twitter campaign. Museum experiences are a unique challenge because they usually give visitors a free choice of what to do. Unlike tightly-crafted forms of performance like opera or film, the performative museum experience (especially exhibition-based ones) allow visitors to construct their visit as they go. This very aspect makes museums a rich medium for visitors to do identity work. Visitors might choose to walk clockwise around a room, or anti-clockwise. They might stop in the middle and look at one work for an hour, or skip a room entirely, or document their visit on their Instagram story, or propose marriage to their partner. The balance between what a museum intends and how a visitor applies their agency is constantly shifting.

Museum experiences emerge in the moment, out of a series of spontaneous decisions made by the visitor in response to what they see, hear and feel around them. In a way, this is improvisation. Like improvised theatre, where performers create scenes and stories by responding to and building on each other’s ideas, the visitor and the museum are working together by performing identity-driven roles to create the museum experience. Using the lens of improvisation can help us better understand and design for this kind of flexibility and empathy in museums.

The foundational philosophy of improvisation is ‘yes and’. Collaborative stories get told faster if you agree with the information your partner contributes, known as their offer, and then build on it. Each offer builds on the previous one.11 When visitors come to a museum, they see a range of offers in the form of an exhibition, a screening, a talk, a café. They ‘yes and’ that offer by going to the exhibition, for instance, and responding to it emotionally, intellectually, socially. But how do museums then ‘yes and’ their offer in return, building on the exchange to achieve shared values?

A hypothetical example will help us to unpack how to achieve this. Let’s say there is a large diamond on display. A visitor might respond by expressing interest in its shape or colour. They might wonder about its crystal structure. They might be angered by the structural injustices of the diamond industry. These are all valid and authentic responses. The staff member in the room can build on their reaction of “I love how sparkly it is!” by responding with, “Well, we have a whole wall of glittery things in the next room.”

We can also go below surface readings of what people say to deduce the drivers or motivation behind them. In improvisation this is called the offer behind the offer. Someone who responds to the diamond by saying “my grandfather had one like that” is also signalling that they are interested in heirlooms and social history. A staff member might respond by pointing them to other objects in the exhibition that have interesting family lineages.

By responding to ‘the offer behind the offer,’ we move from responding to what visitors say towards responding to their motivations and drivers. For instance, if a visitor is about to touch an off-limits sculpture, that suggests they want to get closer to it or understand more about it. A museum staff member can ‘yes and’ this offer by telling them more about its materials, about its fragility, about the oil in their fingers. The visitor gets ‘closer’ to the object, without us having to file an incident report with the conservation department. In this way, conversation aids conservation and builds shared values.

The importance of visitor motivation is already well established in the cultural sector. Both John Falk’s analysis of visitor motivations and Culture Segments developed by Morris Hargreaves McIntyre gather visitors into broad groups based on what they want from cultural experiences.12 The challenge faced by the performative museum is to bring the motivations of visitors and museums together so they work in harmony, each being fulfilled through a shared experience with the other.

Everything that a museum provides its visitors can be considered as a starting ‘offer’ that expresses the museum’s motivation. Our visitor might respond by yes-and-ing one of these ideas, such as attending an exhibition for instance, which demonstrates their motivation. A participatory exhibition might then go one step further, accepting this offer by incorporating a spot for the visitor to respond to what they’ve experienced. But this is usually where it stops. Museums tend to not be very good at continuing the exchange of yes-and with visitors, taking on board their contributions and building on them. Museums are very good at explaining to visitors the benefit of having interacted with them, but poor at understanding the benefit of the museum having interacted with the visitor. Ed Rodley has questioned the “vogue for [museum] storytelling isn’t in some way [a] reaction against learning better listening skills. Storytelling allows us to focus on the part we like: we talk, you listen.”13

Museums are sites of human exchange, not static spaces. Museums will evolve through understanding why two-way interaction with visitors benefits organizations. The bond between museum and visitor can be built if this relationship is reframed as being reciprocal, and working practices are implemented that allow staff to achieve it. Museum growth, in the form of visitor engagement and impact, can be realised if this symbiotic relationship is embraced.

The performative museum is a new understanding of the museum as a site that evolves through the active and ongoing exchange of interactions with visitors. Strategically, this is a shift from the social role of the museum as a trusted and authoritative source of information that works towards education as an outcome. If instead museums work towards belonging and identity-work as a shared outcome with visitors, they need to be intentional and clearly articulate their behavioural norms to achieve an intuitive visitor experience. Without clearly articulated intention, spaces will be performative, but in ways that might feel alienating or confusing to visitors. Within this, performative museums can leverage the unique ‘choose your own experience’ aspect of their organization by responding to the motivations behind their visitor responses. By understand the theory outlined in this paper, which underpins the complex system that is the visitor-centered museum, staff at all levels can work together to bring the performative museum to life.

Notes

- Kylie Budge and Alli Burness, “Museum objects and Instagram: agency and communication in digital engagement,” Continuum, volume 32, no 2 (2018): 137 – 150 and Maria Paula Arias, “Instagram Trends: Visual Narratives of Embodied Experiences at the Museum of Islamic Art,” Museums and the Web 2018, https://mw18.mwconf.org/paper/instagram-trends-visual-narratives-of-embodied-experiences-at-the-museum-of-islamic-art/ (accessed February 9, 2019). ↩

- Alli Burness, Megan Estep, Jennifer Kidd, and Chad Weinard, “Putting People in the Picture: Learning from Museum Visitor Social Photos,” Conference Presentation, Museum Computer Network, New Orleans, LA, https://youtu.be/lQ9Yvpxph8Q (accessed February 9. 2019). ↩

- Sophie Haigney, “The Museums of Instagram,”The New Yorker, September 16, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-museums-of-instagram (accessed February 9 2019). ↩

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (New York: Routledge, 1999), xv. ↩

- Chris Flink quoted in Scott Doorley and Scott Witthoft, Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 38-52. ↩

- Jay Rounds, “Doing Identity Work in Museum,” Curator: The Museum Journal, Volume 49, Issue 2, April 2006, 133 - 150, 133. ↩

- Kingsley Jayasekera, “China Unlimited: Understanding the Museum Boom in China,” Communicating the Museum, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=106&v=ZV_bWc1OA5c (accessed February 9, 2019). ↩

- Alli Burness, “New Ways of Looking: Self-representational social photography in museums,” Museums and Visitor Photography: Redefining the Visitor Experience, edited by Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, 90 - 127. Museums Etc, 2016. ↩

- Richard Holledge, “Down with Blockbusters! James Bradburne on the art of running a museum,” Financial Times, January 22, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/dc3e411c-f20b-11e7-bb7d-c3edfe974e9f (accessed February 9, 2019). ↩

- Kees Dorst, Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking By Design (Boston, Ma: MIT Press, 2015), 45 - 53. ↩

For example, an improv scene might progress like this:

↩“We’re sisters”

“Yes, and we’ve inherited our mother’s business”

“Yes, and she was an assassin.”

“Yes, and we need to avenge her murder!”

- John Falk, Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2019), and Morris Hargreaves Mcintyre, Culture Segments, https://mhminsight.com/culture-segments (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Ed Rodley, Twitter Post, June 23, 2017, 10.40pm, https://twitter.com/erodley/status/878231357813665792 (accessed February 9, 2019). ↩

Bibliography

- Arias, Maria Paula. “Instagram Trends: Visual Narratives of Embodied Experiences at the Museum of Islamic Art.” Museums and the Web 2018, January 14, 2018. https://mw18.mwconf.org/paper/instagram-trends-visual-narratives-of-embodied-experiences-at-the-museum-of-islamic-art/ (associated February 9, 2019).

- Budge, Kylie, and Alli Burness. “Museum objects and Instagram: agency and communication in digital engagement.” Continuum, volume 32, no 2 (2018): 137 - 150.

- Burness, Alli. “New Ways of Looking: Self-representational social photography in museums.” Museums and Visitor Photography: Redefining the Visitor Experience, edited by Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, 90 - 127. Museums Etc, 2016.

- Burness, Alli, Megan Estep, Jennifer Kidd, and Chad Weinard. “Putting People in the Picture: Learning from Museum Visitor Social Photos.” Conference Presentation. Museum Computer Network, New Orleans, LA, 2016. https://youtu.be/lQ9Yvpxph8Q (accessed February 9, 2019).

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge, 1999.

- Doorley, Scott, and Scott Witthoft. Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Dorst, Kees. Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking By Design. Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

- Falk, John. Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2019.

- Haigney, Sophie. “The Museums of Instagram.” The New Yorker, September 16, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-museums-of-instagram (accessed February 9, 2019).

- Holledge, Richard. “Down with Blockbusters! James Bradburne on the art of running a museum.” Financial Times, January 22, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/dc3e411c-f20b-11e7-bb7d-c3edfe974e9f (accessed February 9, 2019).

- Jayasekera, Kingsley. “China Unlimited: Understanding the Museum Boom in China.” Communicating the Museum, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=106&v=ZV_bWc1OA5c (assessed February 9, 2019).

- Mcintyre, Morris Hargreaves. Culture Segments. https://mhminsight.com/culture-segments (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Rodley, Ed. Twitter Post. June 23, 2017, 10:40pm. https://twitter.com/erodley/status/878231357813665792 (accessed February 9, 2019).

- Rounds, Jay. “Doing Identity Work in Museums.” Curator: The Museum Journal, Volume 49, Issue 2, April 2006, 133 - 150.