Chapter 14. Teachers Gonna Teach Teach Teach Teach Teach: Capturing the Now-Visible Meaning Making of Users of Digital Museum Collections

- Darren Milligan

Introduction

Humanizing, from a digital learning perspective, encompasses our ability, as institutions, to first discover and then understand (to collect, study, and use this knowledge to change our own practice) the creative and educational re-uses of our collections. This includes the information that is created outside our walls, both physical and digital, including when it falls far afield from the interests or comforts of our curators and museum educators. It means we design and support internal cultures that elevate and value co-creation, and develop technical infrastructures to collect and understand what less than a generation ago might have seemed iconoclastic. The contextual multiplicity that is created through collaboration between expert and non-expert, between institution and citizen, made possible through an emerging re-prioritization like this, has an important role in the future of museums. Perhaps more importantly, is its role in the future of education. Humanizing requires understanding and valuing the humans we, as cultural institutions, serve. This seems like a simple statement, but it is one that is packed with significant historical, cultural, and technological challenges.

Our Information Museums

The term ‘information society’ was first used in Japan as early as 1964, by Michiko Igarashi, who, using the Japanese term joho shakai, or information society, or information-conscious society, introduced a phase that would quickly be adopted to describe a society and then an economy in a post-industrial era.1 Although many nuanced definitions of the term exist,2 generally an information society is one in which “the creation, distribution, use, integration and manipulation of information is a significant economic, political, and cultural activity.”3 Within this definition, it is clear to see how museums are not anachronistic, but rather a vital player in a society structured upon the use of information. This vital role is one that since the 1960s Americans have more and more begun to expect from their cultural and scientific institutions. Williams describes the change as, “Once the quiet, undisturbed sanctuary of scholars and researchers, museums were seen now as public trusts with duties and responsibilities to their collections, to their communities, and to future generations.”4 Macdonald and Alsford call the museum an “information utility.”5 This definition relies on what have always been described as the key functions of museums, from preserving, studying, exhibiting, and interpreting objects, all roles that involve information about the objects, not focused solely on the objects themselves. Within this context, they call for museums to see themselves as producers of information, that the “primary resources, or commodity, of the museum business as information, rather than as artifacts.”6 This mental framework allows us to easily see the museum’s role in an information-dependent society.

But being aware of or acknowledging those using museum information cannot be merely an academic analysis. We need to respect them, their perspectives, and their hopes. We need to value their knowledge as much as or more than our own. Engagement in social media, that is effective engagement, has taught us that this depth of respect can be practiced within the informational roles we serve, as Spruce and Leaf observe, “While museums often focus on ‘teaching’ the public, social media provides the opportunity for us as an institution to learn. We can learn about our audiences and we can certainly learn from them.”7

To translate behaviors that perhaps first emerged within the context of online social engagement to the entire growing digital ecosystem of the internet, that is both the breadth and depth of the digital engagement of the lives of our audiences, is the work of a generation. It will require both cultural and technological evolutions to achieve. Our digital audiences will always be larger than our physical ones. Always. So, how do we understand our “users,” to learn to love them and the work that they do, and to bring their experiences, the contexts that they understand and create, into the knowledge that we protect and share?

Education at the Vanguard

As museums look to document and understand the impact of digitization and digital access, one of the best place to look is in the education space. Understanding how teachers are accessing, creating, and sharing open educational resources, that is “teaching and learning materials that you may freely use and reuse at no cost, and without needing to ask permission,”8 can allow us to understand teachers as makers, as creators, and highlight how we could encourage, support, and collaborate in these efforts. It will give to us a rich understanding of the potential for digital objects that is most in line with our own, that is to facilitate learning, as Parry and Sawyer articulate,

From temples of sacred objects, to repositories of colonial trophies, and from monuments of civility, to spaces for self-expression and empowerment, the share, the function and the appeal of the museum through history and across cultures has been fashioned by the preoccupations and expectations of each society that has chosen to construct them.9

In the late twentieth century museums began to change in a period now referred to as ‘new museology,’ in which museums were expected to respond to the needs of their audiences driven by the public’s reevaluation of the potential for museums to have impact in their education and lives (both locally and globally).10 Museums began to experiment with the use of digital tools as soon as these tools became readily accessible, going online in the mid 1990s. Soon after, some institutions too began experimenting with how broadly accessible tools, such as the World Wide Web might impact their traditional practices. The public’s new expectation for participation has led to what Silverman has called a “third age of museums.”

One that is defined not only by their important and impressive collections…and not just by their roles as educational institutions, museums have entered an age of social service. One that emphasizes the use of their collections…to foster change in our communities, our neighbors, and our world.11

Museum-Supported Participatory Culture

From the creation and selection of new pop stars to the scope and contents of museum and gallery exhibitions; access, discovery, and our participation through digital technologies have profound impacts on the designation of what we find valuable in our lives. Historically the process of valuation of cultural heritage was designated solely to official organizations, the museums and other cultural agencies staffed with experts and given the societal and often governmental authority to make these decisions on our behalf. The Web now provides us with opportunities to access and connect directly with these organizations to voice our opinions, share our experience, and play a participatory role in the creation of new cultural information, to act as co-curators.

The accessibility and discoverability of information in our increasingly digitally-enabled world (in the United States, 89% of adults are current Internet users12) is important to consider in the space of cultural heritage, one historically tied so closely to limited access to physical objects and spaces. Technologists at leading museums have begun asking, “If you can’t Google something does it exist?.”13 Indeed, if we cannot find and understand what is part of our heritage, how can we participate in its designation, scholarship, and preservation? To respond to this, many museums are now devoting extensive resources to increasing accessibility through creating digital “surrogates.” Inherent to providing increased access through digitization, museums are also developing mechanisms to improve the discoverability of their content. In other words, putting images of collections online is only the first step in ensuring that digital heritage content is available to the public when and where they need it. To achieve this, they are developing extensive metadata (the structured information that “describes, explains, or locates”14 a specific item’s content) programs to ensure that search engines can direct their users properly. This data is being connected through standards-based programs, like LODLAM (Linked Open Data in Libraries and Museums) who aim to connect professionals and enthusiasts intent on enhancing the usage of library and museum material through improved discovery.15 In addition to providing their own metadata, they are developing web-based tools to open their collections to their users to create their own descriptive language (often called folksonomies). These user-generated tags have significant impact on navigation and discoverability, and scale when an institution combines its own metadata with this participatory descriptive language.16

Participation at Our Cultural Core

Much of what we experience through the web is already mediated by participatory or crowd-influenced efforts. The content and placement of online advertising are influenced directly by other user’s interaction with them.17 The ways we shop online including what items we locate as we browse are directly affected by what we and others have done before.18 Sites like Reddit19 use direct methods of user voting and behavioral analysis to evaluate the relevance of and give value to popular online news and content, a role once reserved for newspaper editors or owners. We now live in what Henry Jenkins calls a “participatory culture.” He defines it as one with “strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations,” having a structure for “informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices,” and “where members believe that their contributions matter.” This all coalesces within a space in which the members of the culture have some degree of social connection to each other.20

The growing expectations for cultural institutions to play an important role in participatory culture are affecting the way they do their work. Museums in particular face difficult challenges21 as they transition from institutions designed as what historian Ken Arnold would call “containers” for knowledge or culture and “monuments” that provide “a physical permanence as well as an implied symbol of legitimacy.”22 Simon offers a definition of what a participatory cultural institution might be: “a place where visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content.”23

Crowdsourcing, as first defined by Jeff Howe in the 2006 Wired article,24 generally describes the process of distributed or shared problem solving through online participation. Its first implementations may have been commercial,25 but the term is now being used in many ways in the heritage sector to facilitate participatory experiences with audiences by museums, libraries, and archives. These projects are better thought of as an expansion of traditional public engagement efforts. As Owens defines, “They are about inviting participation from interested and engaged members of the public [and] continue a long standing tradition of volunteerism and involvement of citizens in the creation and continued development of public goods.”26

The first entirely crowdsourced exhibition was developed by the Brooklyn Museum in 2008,27 not simply as a popularity contest, but a carefully-designed research project, one built to test the ideas set forth in James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds, that an adequately diverse crowd can make better decisions that traditional experts.28 This exhibition, Click!, explored the ways that the museum’s audience, one now expanded by the Web, could participate both by submitting photographic work and evaluating it, in the process of exhibition development. While the exhibition through the lens of traditional art critique was not considered a success,29 30 it provided invaluable research data as a model for future projects. It represents that “there is dynamic tension between what the museum wants to present and what participants, visitors, and reporters want to experience.”31 Museums have continued to explore the potential of crowdsourcing in ways ranging from large projects like this to smaller initiatives, however most have focused on collaboration to support the needs of the institution, for example the growth in popularity with volunteer transcription platforms (the Smithsonian’s alone reports more than twelve thousand participants)32 and not found the opportunity for true user-driven co-creation.

Education-centered Participatory Culture, or Users As Makers

In 2005, Dale Dougherty of O’Reilly Media coined the term “Maker,” not just to describe what is an age-old practice of tinkering and crafting at home, but rather to signify, as Anderson points out, a radical change in the way that our societies and perhaps economies will function in the future: “our tinkering in workshops and garages and kitchens was a solitary hobby rather than a true economic force. That is changing. The world of do-it-yourself has gone digital, and like everything else that goes digital, it’s been transformed.”33 But what is a maker? How is the practice of home or community-based creating different now? In her view, Ridge explains that “making” covers a wide range of activities, from fixing something that is broken, tailoring things, making new things, photography, music making, cooking new dishes, etc. It is defined through a process of transition, from merely consuming content, ideas, or products, to producing them oneself.34 Makers are DIYers, or do it yourselfers, but they have taken what they do and put it online.35 This digital expansion facilitates connections that would not have been possible in the past. The DIYers have joined together to create a movement. Anderson clarifies, “what turns them into a movement is the intellectual infrastructure that allows makers to reflect on what it means to be a maker.”36

Makers in Teaching and Learning

The Maker Movement has become an important pedagogical framework in formal education. The Open University Report in 2013 includes maker culture alongside emergent forces with the potential to transform education, like Massively Open Online Courses, alternative credentialing (badging), and learning analytics. Making may have a potentially profound impact of how young people learn. In their words, recent changes in networked technologies “enabled wider dissemination and sharing of ideas for maker learning, underpinned by a powerful pedagogy that emphasizes learning through social making.”37 This “constructionism,” a phrase coined by Seymore Pappert is a continuation of Piaget’s learning theory of constructivism,38 a process by which learning occurs at the intersection of one’s experiences mediated by prior knowledge as well as the experiences of others.39

Constructionism—the N word as opposed to the V word—shares constructivism’s view of learning as ‘building knowledge structures’ through progressive internalization of actions… It then adds the idea that this happens especially felicitously in a context where the learner is consciously engaged in constructing a public entity, whether it’s a sand castle on the beach or a theory of the universe.40

What can be said for the process of making in a different kind of space: a digital space? One example is from the education world and supports the rapid process of classroom change being driven by the growing demands for personalized learning. This evolution aspires to break schools from what has been an industrial-era structure to one more responsive to active learning customized for each student.41 Growing from this demand, many online lesson plan builders have been developed to assist teachers in creating flexible digital learning resources. Blendspace is one such tool.42 On this web-accessible platform, users can search from across digital media repositories and aggregators, such as YouTube and Google Images, and collect, structure, and share digital learning resources.

Museum Digital Maker Spaces

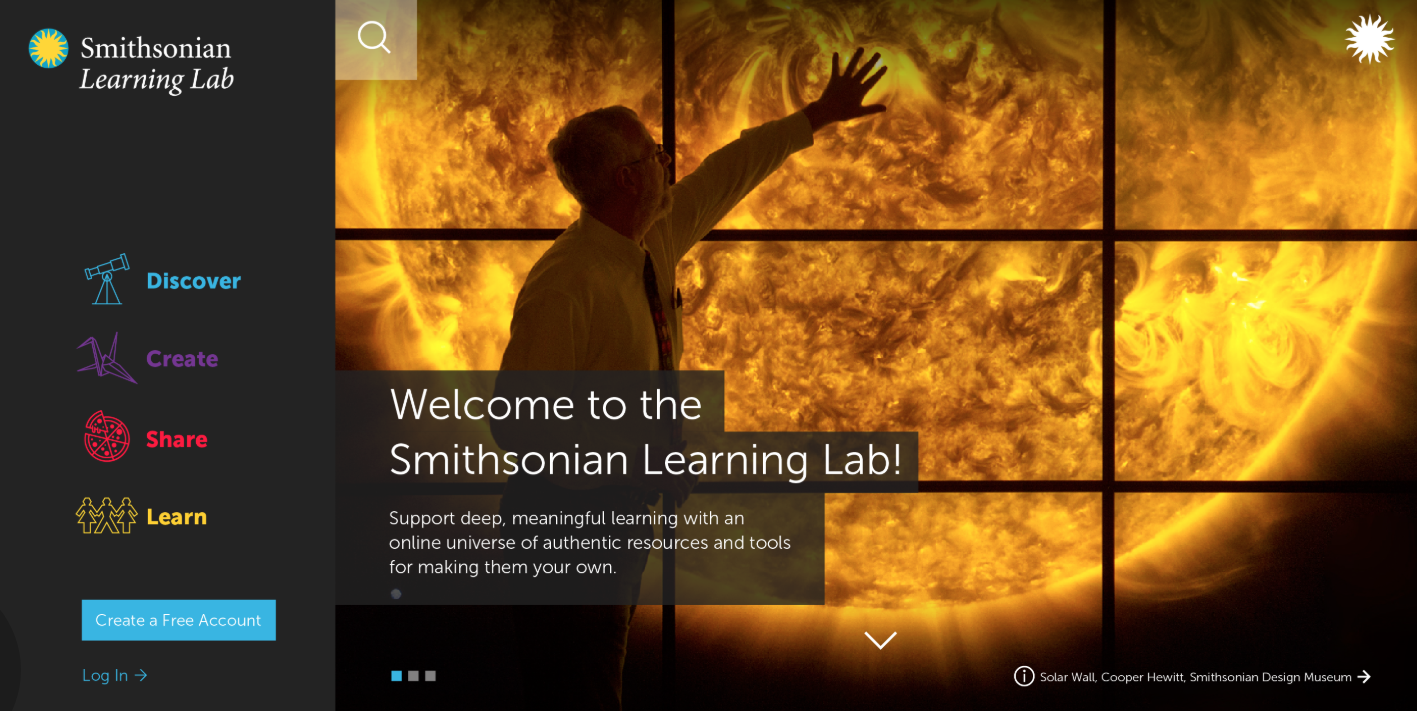

The Smithsonian established the Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access, where I work, in 1976 to serve public education by bringing Smithsonian collections and expertise into the nation’s classrooms. To understand the needs of teachers, students, and museum educators, the Center spent more than a decade in active experimentation and research, culminating in the launch of a new online platform—the Smithsonian Learning Lab (Figure 1). The Learning Lab is a toolkit that encourages the discovery of more than 3 million digital museum resources, tools for the creation of interactive learning experience based on these resources, and a platform for the publishing and sharing of these new approaches. Since its launch in 2016, hundreds of thousands of museum and classroom educators have used the Lab’s tools to create tens of thousands of new examples—ranging from experiments to models—for using Smithsonian resources for learning.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Having an in-house platform for observing the behavior of educational users will have important consequences for the Center’s work. For the first time, we can see and ideally understand the wide contexts provided to digitized collections through their purposeful aggregation and layering with instructional strategies.

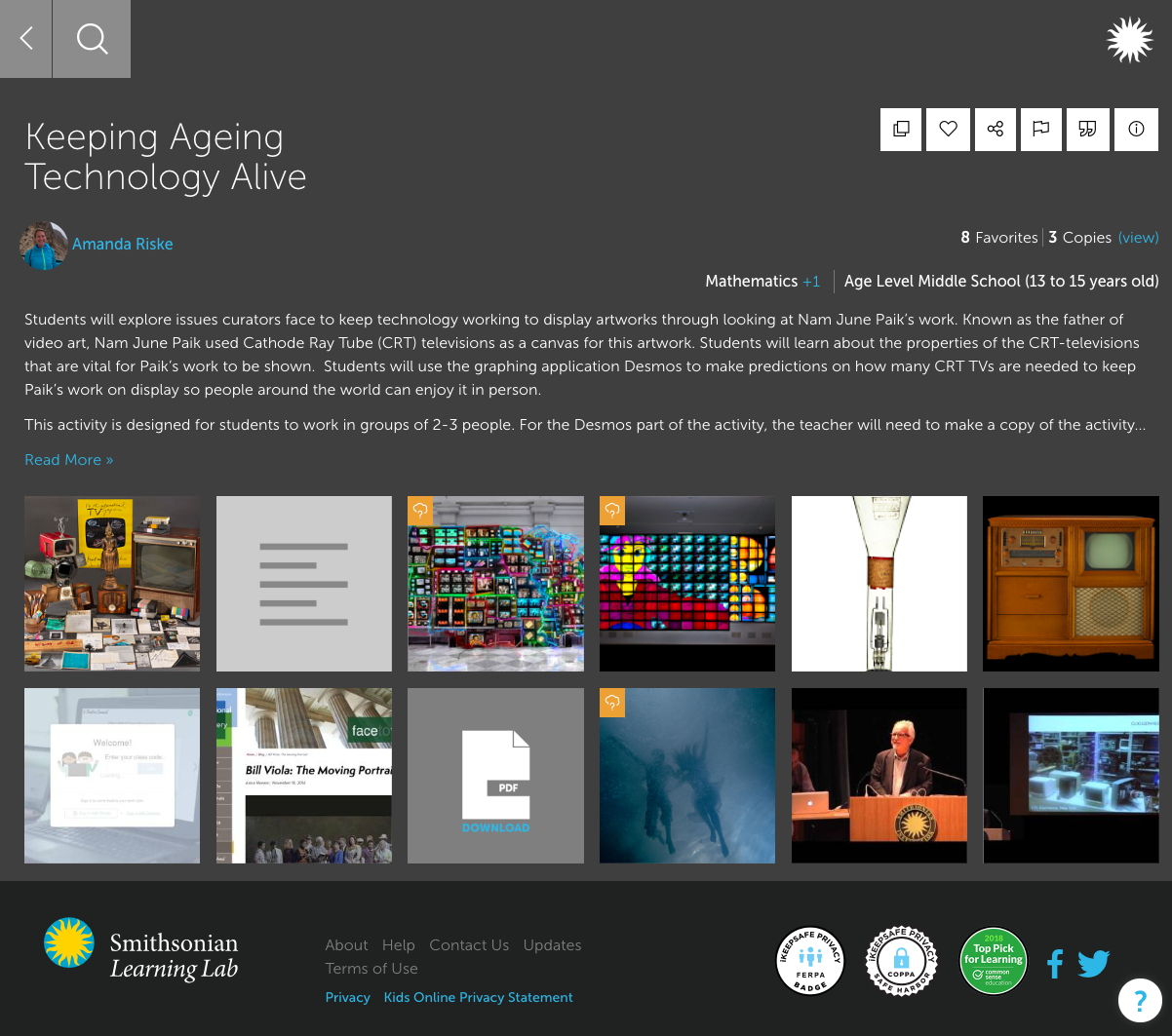

For example, let us look at one artwork, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, by Korean American artist Nam June Paik. Paik came to the United States in the 1960s and was influenced by the diversity of American culture and also of the technology that spread American identity to people across the world. In the mid 1990s he made this sculpture out of more than 300 televisions and neon tubes structured into a map. Videos playing on the screens within each state represent symbols or ideas, sometimes stereotypes, of Paik’s ideas of this America identity.43 This work resonates with so many visitors because of the obvious geographic connections, and because if its sheer electricity and scale (it is approximately 15 X 40 feet in size). Young and old flock to it and it turns out that it resonates with students in the classroom. Through the Learning Lab platform, we have begun to see, for example, a middle school mathematics teacher using Superhighway in a lesson in which students determine the longevity of the work by calculating the lifespan of cathode ray tubes (Figure 2). In another created by an English language arts teacher, students compare the representations of Americans, as shown in the artwork’s videos from each state, to how they are represented in a work on contemporary fiction. And in another, an early learning instructor uses Superhighway, along with images of artifacts and other museum artworks, to introduce the concept of electricity to preschoolers.

Figure 2

Figure 2

These non-canonical ways of using museum collections for learning are not necessarily emergent twenty-first century behavior of teachers. In the early twentieth century, the Philadelphia Commercial Museum loaned extensively to Pennsylvania public schools both teaching materials, such as lecture slides and scripts, but also collection objects. We can assume those teachers were using these materials not exclusively as they were designed, but transforming them to best suit their needs.

… the materials in the lending collections are functioning, educationally, to better advantage than do many of the class trips to museums simply because the teacher receives her material when she needs it and when it fits into the work being done.44

Early research leading to the development of the Learning Lab indicated just this, that most teachers viewed the educational resources designed and prepared by museums as starting points for their teaching.45 What has changed for teachers is both the ease of access to digital resources coupled with demands to design, modify, and teach using open and customizable digital lessons, and for museums is the access to large quantities of data that document their work with this material. There appears to be a great opportunity for museums to connect their collections and goals with those ready to use and make, and to use this information in new ways.

The tenets that define the scope of a space like Blendspace or the Smithsonian Learning Lab: create, share, and connect, are the same that define the maker movement. Connections to content, knowledge, and the tools both for design and production are what create a makerspace, and the connections to others and the sharing of what has been learned and made creates a movement. How do we, as museums, capture and understand all this new knowledge?

Capturing, Understanding, and Institutionalizing Participation

Institutions more than ever are responding to their communities’ need for broad access, highly discoverable content, and opportunities to participate in the curating and creation of culture heritage. However, why are so many still slow to adapt to this evolving model? It is simply an opposition to their loss of authority, or as Simon points out, museums may be slow to change due to the lack of data about the impact of these changes, “lack of good evaluation of participatory projects is probably the greatest contributing factor to their slow acceptance and use in the museum field.”46 Obviously, these transformative changes have affected how the public interacts with culture heritage and assigns it value, but how can this be measured? Is the value associated with the educational resources created by a teacher for her classroom on the Learning Lab, for example, the same as that belonging to a curatorial description about a famous and popular artwork?

To Measure and Record It Is to Value It

Simon Tanner, a museum researcher clarifies the question that museums need to be asking in reference to web-mediated experiences by defining value as “measurable outcomes arising from the existence of a digital resource that demonstrate a change in the life or life opportunities of the community for which the resource is intended.”47 This model48 provides, perhaps for the first time, a clear methodology for cultural institutions to understand how the growing needs for digital access and participation will continue to impact how we define and assign value to our shared cultural heritage and perhaps provide incentive for our traditional heritage organizations to catch up and develop the approaches to understanding and documenting this work.

In a 2012 report, “New Contexts for Museum Information,” Nick Poole, the then CEO of the Collections Trust, offered his thoughts on the future of collections managements systems (CMS), the software that museum use to collect all the information known about museum collection objects. He details nine characteristics, in the areas of integration with other museum services, content, and usability, which organizations and those developing CMS should adopt.49 In the same year, at the Museum Computer Network conference in Seattle, a group of museum information professionals from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and the National Gallery New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa discussed major trends that have now become common facets of museum practice and the informational needs that they require. Their suggestions call for several crucial additions to account for the growing importance of the public’s role in interacting with collections and contributing to the knowledge around museum collections, in particular,

the importance of linking collection data;

the workflow around the acquisition, verification, and incorporation of user-generated/co-generated knowledge; and

the tracking, cataloging, and analyzing of second-generation content

Simon sees the institution as a ‘platform’ to connect content with creators, distributors, collaborators, and more.50 The museum, in this context, becomes a culture system that supports, captures, and shares the work of those interacting with the museum resources digitally. The systems that enable these processes and manage the data surrounding them (such as CMS) need additional functionality to support these new types of digital interactions.

In a 2012 presentation at the Museum Computer Network conference, Adrian Kingston, the Collections Information Manager at the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, identified three major trends impacting museums, that also impact the mechanisms that we use to manage the data around collections.51 These trends are no longer emergent, but rather have become core functionality within the museum. First, Kingston identifies the changing nature of what we collect, that material falling under the category of intangible heritage, or those materials that come to collections in digital format or are born digital within our institutions. Second, he agrees with Simon, on the growing role of user-generated, co-created, or user-submitted content. How do we manage and preserve the content (as well as information about its origin, usage policy, etc.) submitted to us through the various digital channels and platforms where museums now operate? Finally, he wonders at the role of object use, beyond how the museum uses a digital asset on its own website or within exhibitions, but rather data about how our digital surrogates (or born digital material) are being used outside of traditional museum functions. These trends are important and need systems and workflows to manage them and ensure that their place within the institution and the contexts they provide are preserved.

Next Steps

As Adair, Filene, and Koloski point out, the current trends in the valuation of user-generated content, or “bottom up” meaning making with the museum stem from the legacy of the decentralization of elite culture and the widening of access that began in the emergent ‘information society’ of the 1960s.52 Now though, it is generally acknowledged, and even codified as “Joy’s Law,” (named for co-founder of Sun Microsystems, Bill Joy) that generally speaking, even at the most elite institutions, the “smartest people work for someone else.”53 Far removed from the once-perceived universal expertise of museums, cultural institutions now recognize that budgets will never, for the foreseeable future, allow the creation of curatorial staffs large enough to adequately catalog, research, much less understand, the vastly diverse collections that even small museums hold. The role that the public plays in helping museum understand the functions and multiple histories of its collections will continue to be irreplaceable in the operations of museum information systems moving forward.

Through digitization, the public is able also to pursue their own goals, to discover, adapt, create, and share what they have made using museum collections. When the public begins using museum collections in this way, truly becoming makers, museums must be able to acknowledge, capture, and understand this behavior. This moves beyond the augmentation of what we know about objects to understanding the contemporary use of them in our society. CMS must evolve to ensure that we do not lose the valuable knowledge contained within the understanding of how objects are used, the second-generation content (specifically use beyond our own spaces within exhibitions or on our websites). The information on how an object is used, as Kingston states,54 should become part of the history of that object.

There is long list of CMS functional enhancements to make this a reality unfortunately, and while some (such as usability improvements) are already part of most software product lifecycle improvements, others (such as tracking of external usage of collections and collection information) have no technological mechanism to build upon. They represent both a change in the institutional acceptance of the value of this kind of information, but also a technological leap in the ability to capture and understand this data. As software companies and museums begin building or enhancing their CMS, it may be helpful to think of them more as “workflow engines,”55 integrated deeply with the other systems that manage and move data throughout the museum.

Beginning in 2014, the Digital Library Assessment Interest Group of the Digital Library Foundation created a working group to establish best practices for a wide variety of library assessment, including a working group focused on content reuse. Their initial survey concretely describes the challenges facing institutions (in particular libraries, but the same could be said for museums and others) as historical assessment of impact was based exclusively on access.

These types of statistics do not provide a nuanced picture of how users consume or transform unique materials… This lack of distinction makes it difficult for institutions to develop user-responsive collections or highlight the value of these materials. This is turn presents significant challenges for developing the appropriate staffing, system infrastructure, and long-term funding models needed to support digital collections.56

This group, through funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services will work to develop these standards beginning in 2019.

To better gauge the status of this idea, that is, capturing the digital life of museum objects into what might be thought of as an expansion of the idea of a “curatorial file” (that would have historically contained, in a paper file folder, press clipping, conservation treatments, research notes, etc.),57 I conducted an informal Twitter poll by asking for examples of how museums are currently capturing “non-institutional contextualization of digitized collection objects.”58 Through the conversation, examples of components of the cultures and systems needed to realize this were identified, including interesting work at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Imperial War Museums, Wellcome Library, Horniman Museum and Gardens, Princeton University Art Museum, and others.

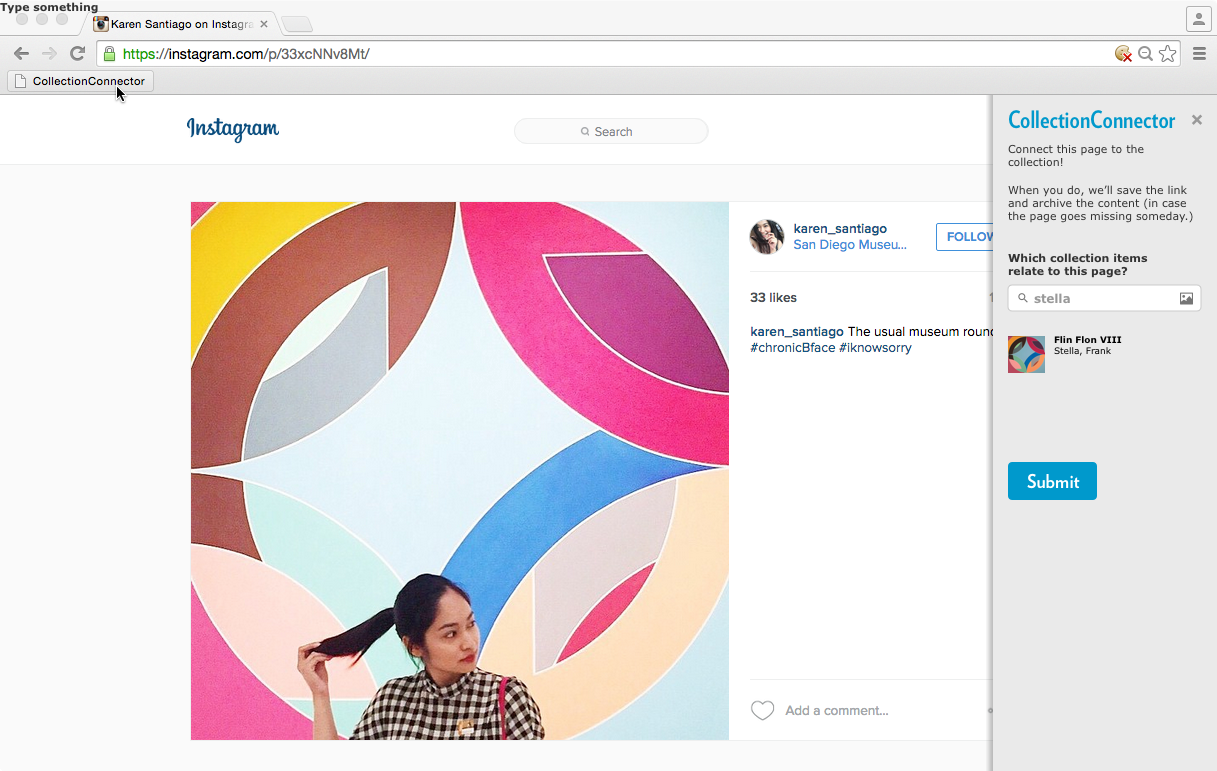

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Balboa Park Online Collaborative has even done some speculative work designing what they called a “Social Collection Connector,” a browser plugin that would enable social media managers to connect and capture media observed on social channels (visitor photographs, for example) to the object record in their CMS (Figure 3). The project, like many of those surfaced through the conversation didn’t proceed due to lack of funding, uncertainties about copyright and privacy, and, I am sure, an inability for our institutions to quickly, as Chan put it, “embrace the notion of both distributed collections and distributed meaning making.”59

What we do now know, however, is that this meaning is being made, that teachers are contextualizing museum narratives, and that students are using digital museum resources in ways that are now incredibly visible to us. It feels too that we are on the verge of systems designed to capture and structure this information in ways that help our institutions learn from these new perspectives. Who will take the next step?

Notes

- Alistair Duff, Information Society Studies (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), pp. 3-4. ↩

- Frank Webster, Theories of the Information Society, Third Edition (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 8–31. ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_society. It should be noted that Wikipedia is not considered by the author an authoritative source for information about the information society, but perhaps a definition collaboratively developed, such as the one provided here from Wikipedia is suitable given the subject matter. ↩

- David Williams, “A Brief History of Museum Computerization,” in Museums in a Digital Age, ed. by Ross Perry (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), pp. 15–21 (p. 16). ↩

- George MacDonald and Stephen Alsford, “The Museum as Information Utility,” in Museums in a Digital Age, ed. by Ross Perry (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), p. 72. ↩

- George MacDonald and Stephen Alsford, “The Museum as Information Utility,” in Museums in a Digital Age, ed. by Ross Perry (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), p. 74. ↩

- Lanae Spruce & Kaitlyn Leaf, “Social Media for Social Justice,” Journal of Museum Education: 42:1, 41-53, 13 February 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2016.1265852. ↩

- For additional information on open education resources, see the ISKME OER Commons, at https://www.oercommons.org/about. ↩

- Ross Parry and Andrew Sawyer, “Space and the machine, Adaptive museums, pervasive technology and the new gallery environment,” Reshaping Museum Space, Architecture, Design, Exhibitions, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005), p. 39. ↩

- John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking, Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning, (Walnut Creek: Altamira, 2000), p. 219. ↩

- Lois H. Silverman, “Social Work of Museums,” Online Video, Bunker Ljubljana, http://vimeo.com/19213313 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Pew Internet and American Life Project (May 2013), http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Charlotte Sexton, “@sdarrough says “If you can’t Google something does it exist?” #mcn2012moma #mcn2012,” Twitter, 10 November 2012, https://twitter.com/cb_sexton/status/267327816406794242 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- National Information Standards Organization, Understanding Metadata, (Bethesda: NISO Press, 2004), http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- John Voss, “About LODAM,” http://lodlam.net/about/. ↩

- Seb Chan, “Tagging and Searching – Serendipity and museum collection databases,” in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, 1 March, 2007, http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2007/papers/chan/chan.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- For additional information on one mechanism of online advertising, see the frequently asked questions for Google Adwords at http://www.google.com/adwords/how-it-works/faq.html. ↩

- For additional information on Amazon’s recommendation engine see http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2012/07/30/amazon-5/. ↩

- For additional information on how Reddit displays content, see http://www.reddit.com/wiki/faq. ↩

- Henry Jenkins, “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Part One),” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 20 October 2006, http://henryjenkins.org/2006/10/confronting_the_challenges_of.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Susan Cairns, “Mutualizing Museum Knowledge: Folksonomies and the Changing Shape of Expertise,” Curator: The Museum Journal, 56: 107–119, 7 January 2013, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cura.12011/full (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Ken Arnold, Cabinets for the Curious: Looking Back at Early English Museums, (Hants and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), p. 5. ↩

- Nina Simon, The Participatory Museum, (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010), p. preface, http://www.participatorymuseum.org/preface/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Jeff Howe, “The rise of crowdsourcing,” Wired 14(06), 14 June 2006, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Daren C. Brabham, “Crowdsourcing and Governance,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 10 August 2009, http://henryjenkins.org/2009/08/get_ready_to_participate_crowd.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Trevor Owens, “The Crowd and the Library,” Trevor Owens, 20 May 2012, http://www.trevorowens.org/2012/05/the-crowd-and-the-library/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Elizabeth Merritt, “Crowdsource the Museum?,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, 20 August 2009, http://futureofmuseums.blogspot.com/2009/08/crowsource-museum.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Click! A Crowd-curated Exhibition, Temporary Exhibition, 27 June to 10 August, 2007, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn. ↩

- Ken Johnson, “3,344 People May Not Know Art but Know What They Like,” New York Times, 4 July 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/04/arts/design/04clic.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Robin Givhan, “Proles vs. Pros: An Experiment In Curating,” The Washington Post, 6 July 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/07/03/AR2008070301509.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Nina Simon, “Why Click! is My Hero (What Museum Innovation Looks Like),” Museum 2.0, 11 July 2008, http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2008/07/why-click-is-my-hero-what-museum.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- For more information on the Smithsonian Transcription Center, see https://transcription.si.edu/. ↩

- Chris Anderson, “20 Years of Wired: Maker movement,” Wired, 2 May 2013, http://www.wired.co.uk/magazine/archive/2013/06/feature-20-years-of-wired/maker-movement. ↩

- Mia Ridge, “Bringing maker culture to cultural organisations,” Online Video, VALA - Libraries, Technology and the Future Inc., 6 February 2014, http://www.vala.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=802&catid=139&Itemid=402 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Chris Anderson, Makers, The New Industrial Revolution (New York: Crown Business, 2012), p. 21. ↩

- Evgeny Morozo, “Making It: Pick up a spot welder and join the revolution,” The New Yorker, 13 January 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/13/making-it-2 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Mike Sharples, Innovating Pedagogy 2013: Open University Innovation Report 2, (Milton Keynes: The Open University), p. 5. ↩

- Edith Ackermann, “Piaget’s Constructivism, Papert’s Constructionism: What’s the difference?,” Future of Learning, http://learning.media.mit.edu/content/publications/EA.Piaget%20_%20Papert.pdf (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Martin Ryder, “The Cyborg and the Noble Savage: Ethics in the war on information poverty,” Handbook of Research on Technoethics, (IGC Global, 2008), http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~mryder/savage.html#def_constructivism (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Ackermann, “Piaget’s Constructivism, Papert’s Constructionism: What’s the difference? ↩

- Craig Deeda, Thomas M. Leskob, and Valerie Lovejoy, “Teacher adaptation to personalized learning spaces,” Teacher Development: An international journal of teachers’ professional development, Volume 18, Issue 3, 7 July 2014. ↩

- For additional information on Tes Blendspace, see https://www.tes.com/lessons. ↩

- National Portrait Gallery, National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian American Art Museum Commemorative Guide (LaJolla, CA: Beckon Books, 2015). ↩

- K.A. Wolfrom, “The Rise and Fall of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum: How a Forgotten Museum Forever Altered American Industry,” Independence Seaport Museum, http://www.phillyseaport.org/rise-fall-philadelphia-commercial-museum (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- J. Ito and L. Langa, “Remedial Evaluation of the Materials Distributed at the Smithsonian Institution’s Annual Teachers’ Night,” Smithsonian Center for Education Museum Studies. ↩

- Nina Simon, The Participatory Museum, (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010), p. Chapter 10, http://www.participatorymuseum.org/chapter10/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Simon Tanner, “The Balanced Value Impact Model,” When the data hits the fan!, 23 October 2012, http://simon-tanner.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-balanced-value-impact-model.html (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- See the Balanced Value Impact Model, from the King’s Digital Consultancy Service, accessible at http://www.kdcs.kcl.ac.uk/innovation/impact.html. ↩

- Nick Poole, New Contexts for Museum Information (London: Collections Trust, 2012), pp. 5–6. ↩

- Nina Simon, The Participatory Museum, chapter 1. ↩

- “MCN 2012: The Future of Collections Management Systems,” Online Video, Museum Computer Network, 1 May 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93cR1vqY3Xk. ↩

- Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Koloski, “Introduction,” Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World (Philadelphia: The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, 2011), p. 11. ↩

- Lewis DVorkin, “Forbes Contributors Talk About Our Model for Entrepreneurial Journalism,” Forbes, 1 December 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/lewisdvorkin/2011/12/01/forbes-contributors-talk-about-our-model-for-entrepreneurial-journalism/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- “MCN 2012: The Future of Collections Management Systems,” Online Video, Museum Computer Network, 1 May 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93cR1vqY3Xk (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Nick Poole, New Contexts for Museum Information, 5. ↩

- Digital Library Assessment Interest Group, “Setting a Foundation for Assessing Content Reuse: A White Paper From the Developing a Framework for Measuring Reuse of Digital Objects project,” 25 September 2018, https://osf.io/y9ghc/ (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- For an example of how one institution, the Folger Shakespeare Library describes their curatorial files, see https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Curatorial_files (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Darren Milligan, “Trying to source some examples, anecdotes, or writing on how museums capture (like in their CIS, etc.) non-institutional contextualization of digitized collection objects. This might include: external publishing platforms, social media activity, educational uses. (Please RT),” Twitter, 9 January 2019, https://twitter.com/DarrenMilligan/status/1083012231720247296 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

- Seb Chan, “Seems like this is a job for @webrecorder_io and integrating that with a CI/M/S. And embracing the notion of both distributed collections and distributed meaning making,” Twitter, 9 January 2019, https://twitter.com/sebchan/status/1083174497543348224 (accessed February 10, 2019). ↩

Bibliography

- Ackermann, Edith. “Piaget’s Constructivism, Papert’s Constructionism: What’s the difference?.” Future of Learning, n.d. http://learning.media.mit.edu/content/publications/EA.Piaget%20_%20Papert.pdf (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Adair, Bill, et. al. “Introduction.” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World. Philadelphia: The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, 2011.

- Anderson, Chris. Makers, The New Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business, 2012.

- Anderson, Chris. “20 Years of Wired: Maker movement.” Wired. 2 May 2013. http://www.wired.co.uk/magazine/archive/2013/06/feature-20-years-of-wired/maker-movement (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Arnold, Ken. Cabinets for the Curious: Looking Back at Early English Museum. Hants and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2006.

- Brabham, Daren C. “Crowdsourcing and Governance.” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 10 August 2009. http://henryjenkins.org/2009/08/get_ready_to_participate_crowd.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Cairns, Susan. “Mutualizing Museum Knowledge: Folksonomies and the Changing Shape of Expertise.” Curator: The Museum Journal, 56 (7 January 2013): 107–119. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cura.12011/full.

- Chan, Seb. Twitter Post. 9 January 2019, 7:31 p.m., https://twitter.com/sebchan/status/1083174497543348224 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Chan, Seb. “Tagging and Searching – Serendipity and museum collection databases.” in Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, edited by J. Trant and D. Bearman. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, 1 March, 2007. http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2007/papers/chan/chan.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Click! A Crowd-curated Exhibition. Temporary Exhibition. (27 June to 10 August, 2007) Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York.

- Deeda, Craig, Leskob, Thomas M., and Lovejoy, Valerie. “Teacher adaptation to personalized learning spaces.” Teacher Development: An international journal of teachers’ professional development, Volume 18, Issue 3 (7 July 2014).

- Digital Library Assessment Interest Group. Setting a Foundation for Assessing Content Reuse: A White Paper From the Developing a Framework for Measuring Reuse of Digital Objects project. Digital Library Federation, 2018. https://osf.io/y9ghc/ (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Duff, Alistair. Information Society Studies. London and New York: Routledge, 2000.

- DVorkin, Lewis. “Forbes Contributors Talk About Our Model for Entrepreneurial Journalism.” Forbes. 1 December 2011. http://www.forbes.com/sites/lewisdvorkin/2011/12/01/forbes-contributors-talk-about-our-model-for-entrepreneurial-journalism/ (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Falk, John H., and Dierking, Lynn D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira, 2000.

- Givhan, Robin. “Proles vs. Pros: An Experiment In Curating.” The Washington Post. 6 July 2008. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/07/03/AR2008070301509.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Howe, Jeff. “The rise of crowdsourcing.” Wired 14(06). June 2006. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Ito, J., and L. Langa. Remedial Evaluation of the Materials Distributed at the Smithsonian Institution‘s Annual Teachers’ Night. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Center for Education Museum Studies, 2010.

- Jenkins, Henry. “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Part One).” Confessions of an Aca-Fan. 20 October 2006. http://henryjenkins.org/2006/10/confronting_the_challenges_of.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Johnson, Ken. “3,344 People May Not Know Art but Know What They Like.” New York Times. 4 July 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/04/arts/design/04clic.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- MacDonald, George, and Alsford, Stephen. “The Museum as Information Utility.” in Museums in a Digital Age, edited. by Ross Perry. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

- “MCN 2012: The Future of Collections Management Systems.” YouTube video. Posted by “Museum Computer Network,” 1 May 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93cR1vqY3Xk (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Merritt, Elizabeth. “Crowdsource the Museum?.” Center for the Future of Museums Blog. 20 August 2009. http://futureofmuseums.blogspot.com/2009/08/crowsource-museum.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Darren Milligan, Twitter post, 9 January 2019, 8:46 a.m., https://twitter.com/DarrenMilligan/status/1083012231720247296 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Morozo, Evgeny. “Making It: Pick up a spot welder and join the revolution.” The New Yorker. 13 January 2014. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/13/making-it-2 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- National Information Standards Organization. Understanding Metadata. Bethesda: NISO Press, 2004. http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf (accessed February 10, 2019).

- National Portrait Gallery. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian American Art Museum Commemorative Guide. LaJolla, CA: Beckon Books, 2015.

- Owens, Trevor. “The Crowd and the Library.” Trevor Owens Blog. 20 May 2012. http://www.trevorowens.org/2012/05/the-crowd-and-the-library/LaJolla, CA: .

- Poole, Nick. New Contexts for Museum Information. London: Collections Trust, 2012.

- Parry, Ross, and Sawyer, Andrew. “Space and the machine, Adaptive museums, pervasive technology and the new gallery environment.” Reshaping Museum Space, Architecture, Design, Exhibitions. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005.

- Ridge, Mia. “Bringing maker culture to cultural organisations.” online video. VALA - Libraries, Technology and the Future Inc., 6 February 2014. http://www.vala.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=802&catid=139&Itemid=402 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Ryder, Martin. “The Cyborg and the Noble Savage: Ethics in the war on information poverty.” in Handbook of Research on Technoethics. IGC Global, 2008. http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~mryder/savage.html#def_constructivism (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Sexton, Charlotte. Twitter post, 10 November 2012, 12:08 p.m. https://twitter.com/cb_sexton/status/267327816406794242 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Silverman, Lois H. “Social Work of Museums.” Online Video. Bunker Ljubljana. http://vimeo.com/19213313 (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010.

- Simon, Nina. “Why Click! is My Hero (What Museum Innovation Looks Like).” Museum 2.0. 11 July 2008. http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2008/07/why-click-is-my-hero-what-museum.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Spruce, Lanae, and Kaitlyn Leaf. ‘Social Media for Social Justice.’ Journal of Museum Education, 42:1 (13 February 2017), 41-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2016.1265852.

- Tanner, Simon. “The Balanced Value Impact Model.” When the data hits the fan!. 23 October 2012. http://simon-tanner.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-balanced-value-impact-model.html (accessed February 10, 2019).

- Webster, Frank. Theories of the Information Society, Third Edition. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Williams, David. “A Brief History of Museum Computerization.” in Museums in a Digital Age, edited by Ross Perry. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Wolfrom, K. A. “The Rise and Fall of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum: How a Forgotten Museum Forever Altered American Industry.” Independence Seaport Museum. 2011. http://www.phillyseaport.org/rise-fall-philadelphia-commercial-museum (accessed February 10, 2019).